Showing 44 items matching "lubricant"

-

Greensborough Historical Society

Greensborough Historical SocietyOil Can, H.C.Sleigh Limited, Golden Fleece Home Lubricant, 1948_

This small can held household lubricant . A list of uses is on back of label.Small metal can with blue and yellow label. Has fold down plastic nozzle for pouring oil.On front label "Golden Fleece Home Lubricant"golden fleece, oil cans, household lubricant -

Bendigo Military Museum

Bendigo Military MuseumEquipment - LUBRICANT CASE

Container used to store lubricants for mechanical items with built in tool to be used for its application.Lubricant case - clear plastic round container split into two compartments of two different sizes. Each end screws off with a built in ladle/spanner. Attached to the lid that is used likely to spoon lubricants into the Mechanism of the weapon.Etched into side "Lubricant Case 7790 995".lubricants, weapons -

Trafalgar Holden Museum

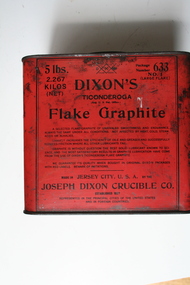

Trafalgar Holden MuseumContainer - Graphite grease

Dixons flake graphite used as a dry lubricantAs imported, used and sold by Holden and FrostRectangular red painted tin with press lid contents and manufacturer printed on tinDixons Flake graphite 5Lb 2.27 kg Nettgraphite, lubricant, dry -

Stawell Historical Society Inc

Stawell Historical Society IncMemorabilia - Realia, 1970's

Clear Glass Ashtray marked for Advertising. Compliments of Heslop's BP Fuels - Lubricants, Heslop Electrics stawell -

Shepparton RSL Sub Branch

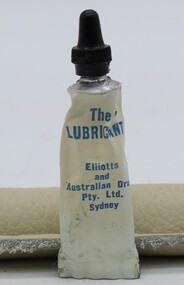

Shepparton RSL Sub BranchProtectors ear drum lubricant

Zinc squeeze tube with white painted with blue lettering and black plastic cap wrapped in fine waterproof paper.The Lubricant Elliotts and Australian drug pty ltd Sydney -

Stawell Historical Society Inc

Stawell Historical Society IncRealia, Heslop's Ash Tray, 1970'2

Advertising for electrical Shop on the corner of Main Street and Victoria PlaceClear Glass ash tray marked for Advertising: Compliments of Heslop's BP. Fuels - Lubricants Heslop Electrics149 151 Main Street Stawell Phone 51803advertising smoking -

Melbourne Tram Museum

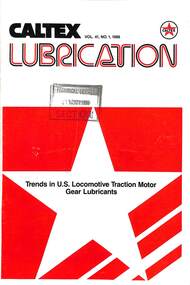

Melbourne Tram MuseumManual, Caltex, "Caltex Lubrication publication re traction motor gear lubricants – locomotives", 1986

Manual - or publication - Caltex Vol 41, No. 1 1986, Lubrication titled "Caltex Lubrication publication re traction motor gear lubricants – locomotives" - 16 pages, centre stapled.Has "Technical Services Section 21 Nov 1986" stamp on front cover.trams, tramways, caltex, equipment, instructions, motors -

Moorabbin Air Museum

Moorabbin Air MuseumBook (Item) - Mirage Iii -0 Electrical Book 3

Description: Mirage Aircraft Fuels & Lubricants Level of Importance: . -

Maldon Vintage Machinery Museum Inc

Maldon Vintage Machinery Museum IncMotor Mower

Cylindrical lawn mower with grass catcher. Green painted catcher and engine cover, orange petrol tank and handles. Pull start with engine control on RHS handle. Name prominantly printed on front of catcher "Qualcast / four stroke / Super 12". Sticker on engine "Stowmarket, SIP (in a red diamond background) Suffolk / Engine type 75G14 Model No. 25A / Made in Englsnd / Recommended Lubricants" followed by a table of lubricant makers and oil specification.machinery, lawn mowing -

Yarrawonga and Mulwala Pioneer Museum

Yarrawonga and Mulwala Pioneer MuseumMachine - Sewing Machine, 1960

Purchased in 1960 as "state of the art"1960 Singer sewing machine Model 411. Spare bobbins, needles, lubricant etc included. Manual also included. Still in perfect condition and working order Machine case in good condition made of wood.model number not visable any longer . In instruction book it indicates model no 411 -

Trafalgar Holden Museum

Trafalgar Holden MuseumFunctional object - Dixons graphite gun

Used for lubricating wagon wheels circa 1900Imported and sold by Holden and FrostShort round tin with conical shaped lidDixon Jet 4 Graph - air gunlubricant, dixons, graphite -

Trafalgar Holden Museum

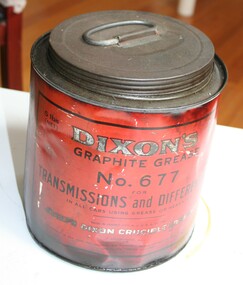

Trafalgar Holden MuseumContainer - Graphite grease

Was used to lubricate Differentials and Transmissions in early VehiclesAs imported and sold by Holden and FrostTin can with screw lid printed with instruction labelDixon's Graphite Grease No677 Joseph Dixon Crucible Company for Transmissions and Differentialsgraphite, grease, lubricant -

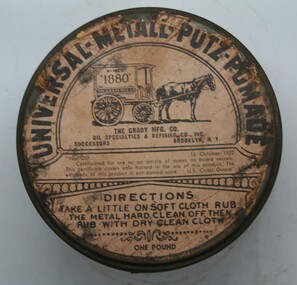

Trafalgar Holden Museum

Trafalgar Holden MuseumFunctional object - Tin can, C1900

Oil used for the preservation of metal C1900Imported and sold by Holden and FrostRound tin with horse and cart imprinted on lid with instructions for useUniversal - Metal Putz Pomade Instructions for uselubricant, oil, cans -

Melbourne Tram Museum

Melbourne Tram MuseumDocument - Report, Tramway Board, "Return of fuel & Oil used at ...... Power House during the Month of November 1918", Nov. 1918

Set of reports for the "Return of fuel & Oil used at ...... Power House during the Month of November 1918", listing the amount and value of fuels, lubricants, bearing oil, road pulley lubricants, rope oil and rope tar for various cars houses. Prepared on a pre-printed form. Also lists the length of ropes and the average amounts per mile of rope. Form No.374, 7/17 Gives details for the following Power houses. Richmond Fitzroy Brunswick Johnston St North Carlton St Kilda Esplanade Prahran North Melbourne South Melbournetrams, tramways, cable trams, reports, winding houses, power house, richmond, fitzroy, brunswick, johnston st, north carlton, st kilda, esplanade, prahran, north melbourne, south melbourne -

National Vietnam Veterans Museum (NVVM)

National Vietnam Veterans Museum (NVVM)Model - Diorama, Stores Vehicle Roadside Stall

Guntruck escort vehicle and stores truck next to paddy field. Crew appear to be buying refreshments from local villagers. Stores truck is a POL (petrol, oil and lubricants) truck towing a fuel trailer. A wrecked jeep is on the side of the field. Junk dog truck has four machine guns mounted to protect the stores truck.Gun truck bears the name JunkDog. White US stars on the POL truckalso says USA.junk dog, gun truck, diorama -

Melbourne Tram Museum

Melbourne Tram MuseumManual, MAN, "MAN Maintenance recommendations 1985", Jul. 1985

Set of two manuals for MAN buses: .1 - MAN Maintenance recommendations 1985 - 25 A4 pages, landscape stapled in the top left hand corner - issued 7/1985. Photocopied from a MAN book. .2 - Chart of MAN recommended fuels and lubricants - 2 A4 sheets, stapled in the top left hand corner.Has "MAN" in ink on top edge.trams, tramways, buses, maintenance, man, manual -

Melbourne Tram Museum

Melbourne Tram MuseumManual, AEC, Leyland, "Lubrication data for AEC Mk VI bus", c1970

Set of three manuals for AEC and Leyland buses: .1 - Lubrication data for AEC Mk VI bus - Part S72 - photocopy of original document - 5 A4 pages - undated. .2 - Leyland lubrication recommendations 1973 - All models - G47/73 - 10A4 pages .3 - Leyland National Bus lubricants and fluids - 6 A4 pages, c1968.Has "MAN" in ink on top edge.trams, tramways, buses, maintenance, aec, leyland, manual -

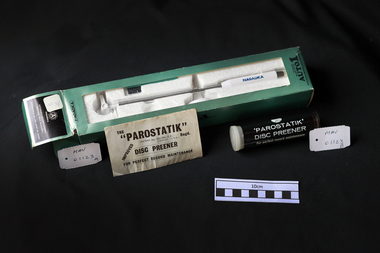

City of Moorabbin Historical Society (Operating the Box Cottage Museum)

City of Moorabbin Historical Society (Operating the Box Cottage Museum)Manufactured Objects, Vinyl record cleaner kit 'NAGAOKA', c1970

a) Nagaoka Record Anti-Static & Disc Guard Kit The Nagaoka STAT-10 is a record protecting agent that serves both to protect your records from static and to significantly reduce record and stylus wear. By using this product you will improve the sound that you hear from your records, but will also protect your records. The unique charge reducing formula significantly reduces the amount of static electricity present on the surface of the vinyl recording. It also reduces the irritating noise produced by the scratches present on the surface of the vinyl recording. This record protecting agent also contains a special lubricant / protecting fluid agent.This lubricant / protecting fluid reduces record wear so that your recordings are as good as new. b) 'PAROSTATIK' Disc preener -: Use while rotating record slowly on Turntable. Press gently during one or two revolutions. Dust collected on plush surface should be removed before re-use. Device has "built-in" anti-static requiring occasional moisture replacement. Remove cap from centre tube withdraw and moisten wick (when dry) with clean water and replace Always return "Parostatik" to case when not in use. Vinyl records became very popular mid 20thC and cleaners were used to preserve the audio quality of the record surface.A box containing Vinyl record cleaning equipment manufactured by a) Nagaoka Pty Ltd Japan and b) 'Parostatik' C.E Watts Pty Ltd England a ) Box : NAGAOKA / A / trademark / NAGAOKA / AUTOMATIC RECORD CLEANER / ORIGINAL BEST PRODUCTS / NAGAOKA & CO LTD. MADE IN JAPAN / AUTOMATIC / RECORD CLEANER / AUTO 1 / NAGAOKA ORIGINAL BEST PRODUCTS b) Packet ; THE / "PAROSTATIK" PATENT .... REGD./ IMPROVED / DISC PREENER / FOR PERFECT RECORD MAINTENANCE Cylinder; Watts / "PAROSTATIK" / DISC PREENER / For perfect record maintenancerecord players, music, vinyl records, moorabbin, bentleigh, cheltenham, japan, nagaoka pty ltd ,, watts c. e. pty ltd, parostatik disc preener, england -

Kiewa Valley Historical Society

Kiewa Valley Historical SocietySewing Machine

Sewing machines were used by some ladies to mend and make clothes for the family as shops were some distance away and bought clothes were much more expensive. The sewing machines were also used to sew items for fund raising e.g.. Church and School fetes.Used in the Kiewa Valley.The machine has a brown wood veneer base and a lid with a metal handle in the centre of the top. There is a long screw that fits in a hole at the top of the lid. The screw can be lifted out and used to open and take off the lid. Inside there is a black metal machine which is fitted onto the wooden base. There is a compartment in the base, right of the wheel of the machine, which holds an instruction manual and a tube of ""Singer" lubricant for electric machines". The light, above the needle is covered by bakelite. A leather belt runs around the wheel on the right to enable the machine to run. There is a foot pedal and an electric cord attached."Singer Manufacturing Company" - gold embossed "No. EL 249 355" - oval disc "99K" - disc "Singer Manfg. Co. - discsewing machine; singer manufacturing company; kiewa valley -

Mont De Lancey

Mont De LanceyGlass bottle, Pitt & Sons

Clear glass liquid paraffin oil bottle with black bakelite screw-on top and label. 3/4 full of liquid.On label: "Liquid Paraffin. Specially prepared for Internal use. Non inflammable. The most modern method of treating CONSTIPATION an d has been found most valuable in chronic cases, the action on the bowels being that of a lubricant. DOSE: from one teaspoonful to 2 tablespoonfuls. To avoid loss of food vitamins, do not use other than at bedtime, except on the advice of a physician. BB 1932 CHEMICALLY PURE. PITT & PARTNERS SYDNEY."bottles, containers, medicine bottles -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageEquipment - Suppository Mould

Before factory production became commonplace in medicine, dispensing was considered an art and pill and suppository machines such as these were a vital component of any chemist’s collection. This mould dates back to the days when the local chemist or apothecary bought, sold, and manufactured all his own drugs and medicines to everybody who lived within the local community. In Victorian times, there was no such thing as off-the-shelf medicine. Every tablet, pill, suppository, ointment, potion, lotion, tincture and syrup to treat anything from a sore throat to fever, headaches or constipation, was made laboriously by hand, by the chemist. Some medicines are formulated to be used in the body cavities: the suppository (for the rectum), the pessary (for the vagina) and the bougie (for the urethra or nose). History Suppositories, pessaries and bougies have been prescribed for the last 2000 years but their popularity as a medicinal form increased from around 1840 - suppositories for constipation, haemorrhoids and later as an alternative method of drug administration, pessaries for vaginal infections and bougies for infections of the urethra, prostate, bladder or nose. Manufacture The basic method of manufacture was the same for each preparation, the shape differed. Suppositories were "bullet" or "torpedo" shaped, pessaries "bullet" shaped but larger and bougieslong and thin, tapering slightly. A base was required that would melt at body temperature. Various oils and fats have been utilised but, until the advent of modern manufactured waxes, the substances of choice were theobroma oil (cocoa butter) and a glycerin-gelatin mixture. The base was heated in a spouted pan over a water-bath until just melted. The medicament was rubbed into a little of the base (usually on a tile using a spatula) and then stirred into the rest. The melted mass was then poured into the relevant mould. Moulds were normally in two parts, made from stainless steel or brass (silver or electroplated to give a smooth surface). To facilitate removal the moulds were treated with a lubricant such as oil or soap solution. To overcome the difficulty of pouring into the long, thin bougie mould, it was usual to make a larger quantity of base, to partially unscrew the mould, fill with base and then screw the two halves of the mould together thus forcing out the excess. When cool, any excess base was scraped from the top of the mould, the mould opened and the preparations removed, packed and labelled with the doctor's instructions. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/MuseumLearningResources/05%20Suppositories%20Pessaries%20and%20Bougies.pdf?ver=2020-02-06-154131-397The collection of medical instruments and other equipment in the Port Medical Office is culturally significant, being an historical example of medicine from late 19th to mid-20th century.Proctological mould for making suppositories.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, suppositories, medicine, health -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageEquipment - Suppository Mould

Before factory production became commonplace in medicine, dispensing was considered an art and pill and suppository machines such as these were a vital component of any chemist’s collection. This mould dates back to the days when the local chemist or apothecary bought, sold, and manufactured all his own drugs and medicines to everybody who lived within the local community. In Victorian times, there was no such thing as off-the-shelf medicine. Every tablet, pill, suppository, ointment, potion, lotion, tincture and syrup to treat anything from a sore throat to fever, headaches or constipation, was made laboriously by hand, by the chemist. Some medicines are formulated to be used in the body cavities: the suppository (for the rectum), the pessary (for the vagina) and the bougie (for the urethra or nose). History Suppositories, pessaries and bougies have been prescribed for the last 2000 years but their popularity as a medicinal form increased from around 1840 - suppositories for constipation, haemorrhoids and later as an alternative method of drug administration, pessaries for vaginal infections and bougies for infections of the urethra, prostate, bladder or nose. Manufacture The basic method of manufacture was the same for each preparation, the shape differed. Suppositories were "bullet" or "torpedo" shaped, pessaries "bullet" shaped but larger and bougieslong and thin, tapering slightly. A base was required that would melt at body temperature. Various oils and fats have been utilised but, until the advent of modern manufactured waxes, the substances of choice were theobroma oil (cocoa butter) and a glycerin-gelatin mixture. The base was heated in a spouted pan over a water-bath until just melted. The medicament was rubbed into a little of the base (usually on a tile using a spatula) and then stirred into the rest. The melted mass was then poured into the relevant mould. Moulds were normally in two parts, made from stainless steel or brass (silver or electroplated to give a smooth surface). To facilitate removal the moulds were treated with a lubricant such as oil or soap solution. To overcome the difficulty of pouring into the long, thin bougie mould, it was usual to make a larger quantity of base, to partially unscrew the mould, fill with base and then screw the two halves of the mould together thus forcing out the excess. When cool, any excess base was scraped from the top of the mould, the mould opened and the preparations removed, packed and labelled with the doctor's instructions. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/MuseumLearningResources/05%20Suppositories%20Pessaries%20and%20Bougies.pdf?ver=2020-02-06-154131-397The collection of medical instruments and other equipment in the Port Medical Office is culturally significant, being an historical example of medicine from late 19th to mid-20th century.Proctological mould for making suppositories.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, suppositories, medicine, health -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone in two pieces. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070. Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Rib Bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale rib bone with advanced stage of calcification as indicated by brittleness. None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined