Showing 11 items matching "sperm whale's tooth"

-

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

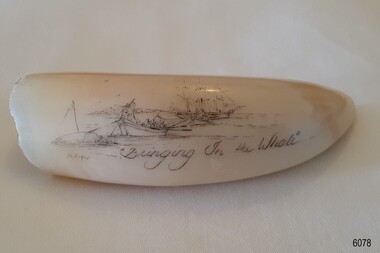

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageCraft - Scrimshaw, Bringing in the Whale

... sperm whale's tooth... whale's tooth. It is one of two pieces by artist Gary Tonkin... This scrimshaw work is done on a sperm whale's tooth. It is one of two ...When scrimshaw is mentioned, most people think of carving on sperm whale teeth only. But scrimshaw also includes engravings on skeletal whale bone–such as the jaw bone, called pan bone and ivory from other marine mammals such as walrus. Although scrimshaw is widely associated with nautical themes and designs of the 19th century whaling industry, vintage scrimshaw was also produced as tribal art in many cultures. Today, scrimshaw is recognized as a unique medium in which present-day artists have developed their own modern themes. Scrimshaw reproductions may take several forms. There are - New carvings on genuine ivory or bone with the deliberate intent to create an "antique” - New carvings on genuine ivory or bone sold as signed and dated contemporary art - Clearly marked synthetic museum reproductions and mass marketed - Unmarked synthetic replicas This scrimshaw work is done on a sperm whale's tooth. It is one of two pieces by artist Gary Tonkin in Flagstaff Hill’s collection. Sperm whales can live for 60 or even 70 years, so the tooth could be quite old. It came from the whaling station in Albany, Western Australia, which ceased processing whales in 1978 and is now a whaling museum. The two works were commissioned by Flagstaff Hill in the 1980s. Tonkin could spend from a few days to a few months in intensive work on each piece of scrimshaw. He is a world-renowned Master Scrimshander and a Fellow of the Australian Society of Marine Artists (FASMA), and lives in Albany, Western Australia. Gary Tonkin, FASMA – Tonkin was born in 1949 in Portland, Victoria, and grew up there with a history of whaling and related industries. He moved to Albany in southwest WA in 1971 and worked as an Export Meat inspector for the Federal Government. This small town also had a historical connection to whaling. The Cheynes Beach Whaling Station was still operating, and there were even three whaling ‘chaser’ vessels at the old jetty. In 1975, his employment now permanent, Tonkin bought an old cottage near the bay, purchased some whales’ teeth, and began learning the sailors’ art of scrimshaw, combining this with his artistic skills and knowledge of history. His job gave him access to buy as many whale teeth as he could afford, straight from the whaling station. Tonkin gained further marine knowledge as he sailed on the schooner ‘Esperance’ from Fremantle to Mauritius in 1988. He watched the sailors at work and experienced the rough and stormy sea conditions first-hand. Tonkin later visited whaling museums, galleries and libraries in England and America to gather reference materials and information on all aspects of whaling and scrimshaw. In 1993 he was Commissioned to engrave six large whale teeth, from the Albany whaling station, for the USA Gallery at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney. This work is now in the museum’s permanent collection. From that time, Tonkin began working full-time as a Scrimshander. Tonkin’s work is now in galleries and museums in America and Australia, as well as in private collections. He is the founder of the Albany Maritime Heritage Association and was the inaugural President. In the 1990s he actively and successfully campaigned for the preservation of the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station in Albany, which is now Whale World, an open-air whaling museum. His continuing work as a Scrimshander contributes to the preservation of the art of scrimshaw and the history of whaling. This scrimshaw represents the ancient craft of scrimshaw, associated with mariners in the whaling trade in the early 19th century. The work is also Nationally significant for being created by world-renowned Scrimshander, Gary Tonkin, from Albany, Western Australia. Scrimshaw; whale tooth carved with an image of two whaleboats hauling a dead whale back to the mother ship. Inscribed Title and signature of artist Gary Tonkin.Inscribed "Bringing in the whale". Signature "G Tonkin"flagstaff hill maritime museum and village, warrnambool, great ocean road, shipwreck coast, maritime museum, flagstaff hill, perth, whaling, whales, australia, scrimshaw, scrimshander, gary tonkin, g tonkin, bone, tooth, craft, albany, western australia, cheynes beach whaling station, whale world, portland, engraving, maritime art, sperm whale's tooth, albany whaling station, albany whaling museum -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Tooth, Probably 19th century

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales possessing teeth, such as the beaked whales and sperm whales. Seventy-three species of toothed whales are described. They are one of two living groups of cetaceans, the other being the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which have baleen instead of teeth. The two groups are thought to have diverged around 34 million years ago (mya). Toothed whales range in size from the 4.5 ft (1.4 m) and 120 lb (54 kg) vaquita to the 20 m (66 ft) and 55 t (61-short-ton) sperm whale. Several species of odontocetes exhibit sexual dimorphism, in that there are size or other morphological differences between females and males. They have streamlined bodies and two limbs that are modified into flippers. Some can travel at up to 20 knots. Odontocetes have conical teeth designed for catching fish or squid. They have well-developed hearing, that is well adapted for both air and water, so much so that some can survive even if they are blind. Some species are well adapted for diving to great depths. Almost all have a layer of fat, or blubber, under the skin to keep warm in the cold water, with the exception of river dolphins. Toothed whales consist of some of the most widespread mammals, but some, as with the vaquita, are restricted to certain areas. Odontocetes feed largely on fish and squid, but a few, like the killer whale, feed on mammals, such as pinnipeds. Males typically mate with multiple females every year, but females only mate every two to three years, making them polygynous. Calves are typically born in the spring and summer, and females bear the responsibility for raising them, but more sociable species rely on the family group to care for calves. Many species, mainly dolphins, are highly sociable, with some pods reaching over a thousand individuals. Once hunted for their products, cetaceans are now protected by international law. Some species are attributed with high levels of intelligence. At the 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, support was reiterated for a cetacean bill of rights, listing cetaceans as nonhuman persons. Besides whaling and drive hunting, they also face threats from bycatch and marine pollution. The baiji, for example, is considered functionally extinct by the IUCN, with the last sighting in 2004, due to heavy pollution to the Yangtze River. Whales occasionally feature in literature and film, as in the great white sperm whale of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick. Small odontocetes, mainly dolphins, are kept in captivity and trained to perform tricks. Whale watching has become a form of tourism around the world. Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toothed_whaleWhale teeth were much prized for use in scrimshaw work.Whale tooth. Significant staining and yellowing. Broken at base, and missing the root.Noneflagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale tooth, whaling, whaling industry, whales -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone in two pieces. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070. Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Rib Bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale rib bone with advanced stage of calcification as indicated by brittleness. None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.Noneflagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Vertebrae, Undetermined