Showing 22 items

matching plans, themes: 'a diverse state','aboriginal culture','creative life','family histories','gold rush','immigrants and emigrants'

-

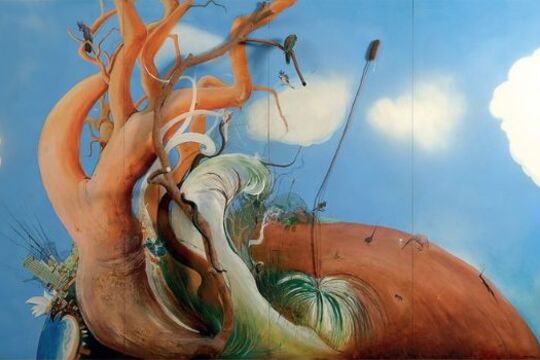

Panorama: A question of perspective

... notion of the panorama originated in military conceptions of the landscape as a battlefield, whereby strategic vantage points are key to tactical planning.[iii] Underlying its transformation into a form of popular entertainment, the panorama is rooted ...TarraWarra Museum of Art is located in the picturesque Yarra Valley in Victoria, Australia.Visitors to the Museum are afforded a spectacular, resonant and panoramic experience of ‘nature’ through the north facing windows. The view stretches towards the distant Toolangi rainforest across planted vines, native bushland and farmland.

The region is surrounded by a spectacular mountain range that includes Mt Baw Baw, Mt Donna Buang, Mt Juliet, Mt Riddell and Mt Toolebewong. As these names attest, we are situated in an area of significant Indigenous history and colonisation. Tarrawarra is a Wurundjeri word that translates approximately as ‘slow moving water’ and is the name given to the area in which the Museum is located.

The Yarra Valley sunsets, soundscapes, seasonal changes, Indigenous histories, ecological vulnerabilities and environmental challenges are in a complex and ever changing entanglement. Since 2012, the Museum has explored this context through special exhibitions and commissions, forums and performances, screenings and lectures. As such, the Museum has sought to understand the complexity of our site, and with that, the broader intersections between art and landscape. Artists provide us the opportunity to ‘see’ the landscape in a different way. They imagine it, call it into being, reflect upon it, animate it, unravel its hidden histories, and expose its ecological sensitivities.

Panorama, the exhibition, was an integral part of this ongoing conversation and imaginative exploration. Our intention was not so much to write a narrative history of Australian landscape painting. Rather, it was to be attuned to the intermingling of voices, points of view, perspectives - colonial and modern, contemporary and Indigenous – that comprise the uniquely Australian persistence to unravel the ‘patter’ of nature.

As a phenomenon to which we are all very accustomed, it is easy to overlook the simple fact that for a landscape to come into being it requires a ‘point of view’, a subjective consciousness to frame a particular expanse of the natural world. As the art historian Simon Schama remarks in his landmark survey on the genre, Landscape and Memory, ‘it is our shaping perception that makes the difference between raw matter and landscape’. [i] The centrality of the viewer’s position in constructing a vista is clearly evident in terms such as ‘perspective’, ‘prospect’, and ‘view point’ which are synonymous with ‘position’, ‘expectation’, and ‘stance’. This highlights that there is always an ineluctable ideological dimension to the landscape, one that is intimately entwined with a wide range of social, economic, cultural and spiritual outlooks. Turning to the notion of the panorama, a brief survey of its conception and infiltration into everyday speech, reveals how our way of seeing the landscape is often tantamount to the formation and delineation of our personal, communal, and national identities.

The term panorama was first coined to describe the eponymous device invented by the British painter Robert Barker which became a popular diversion for scores of Londoners in the late 18th century. Consisting of a purpose built rotunda-like structure on whose cylindrical surface landscape paintings or historical scenes were displayed, ‘The Panorama’ contained a central platform upon which viewers observed the illusionistic spectacle of a sweeping 360 degree vista. With its ambitious, encyclopaedic impulse to capture and concentrate an entire panoply of elements into a singular view, it is telling that this construction would soon give rise to an adjective to describe, not only an expansive view extending in all directions, but also a complete and comprehensive survey of a subject. As the curators Jean-Roch Bouiller and Laurence Madeline argue, these different meanings convey ‘the very essence of the panoramic phenomenon: the central role of perspective, a certain appropriation of the world that follows, the feeling of dominating a situation simply due to having a wide and complete view’.[ii] Indeed, as art historian Michael Newman reveals, the whole notion of the panorama originated in military conceptions of the landscape as a battlefield, whereby strategic vantage points are key to tactical planning.[iii] Underlying its transformation into a form of popular entertainment, the panorama is rooted in a particular form of political authority based on surveying, mapping and commanding the subject of the view.

In this exhibition, the term panorama was invoked to acknowledge that ways of perceiving the landscape have their own histories which have arisen out of particular social, political and cultural contexts. As the landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn contends: ‘In every landscape are ongoing dialogues; there is “no blank slate”; the task is to join the conversation’.[iv]However, far from claiming to present an unbroken view or a complete survey, Panorama challenged the very notion of a single, comprehensive monologue by presenting a series of works which engaged with the discourse of landscape in a diverse range of voices. Taking advantage of the tremendous depth and strength of the TarraWarra Museum of Art collection gifted by its founders Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC, the exhibition was staged in two parts, with a different selection of paintings exhibited in each half. Displayed in distinct groupings which explored alternative themes and concerns, Panorama highlighted the works of key artists who have redefined, expanded and interrogated the idea of the landscape in ways which suggest that it is far from settled.

Further Information

[i] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, New York: Vintage Books, 1996, p. 10.

[ii] Jean-Roch Bouiller and Laurence Madeline, Introductory text for the exhibition I Love Panoramas, MuCEM and the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva, 4 November 2015 - 29 February 2016, URL: http://www.mucem.org/en/node/4022

[iii] See ‘The Art Seminar’ in Landscape Theory, (eds. Rachael Ziady DeLue and James Elkins), New York and London: Routledge, 2008, p. 130.

[iv] Anne Whiston Spirn, ‘“One with Nature”: Landscape, Language, Empathy and Imagination’ in Landscape Theory, 2008, p. 45.

-

Women on Farms

... to work with a group so committed to the idea of providing a forum for women, by women in a way that was comfortable for women.A part of that positive feeling was seeing members of the group supporting each other in the planning process and willing ...In 1990, a group of rural and farming women met in Warragul for what was to be the inaugural Women on Farms Gathering.

A group of local women had developed the idea while involved in a Women on Farms Skill Course. It was to prove inspirational, and the gatherings have been held annually ever since, throughout regional Victoria.

The Women on Farms Gathering provides a unique opportunity for women to network, increase their skills base in farming and business practices, share their stories and experience a wonderful sense of support, particularly crucial due to the shocking rural crises of the last decade. Importantly, the gatherings help promote and establish the notion of rural women as farmers, business women and community leaders.

The relationship between Museums Victoria and the Women on Farms Gathering is a model of museums working with living history.

-

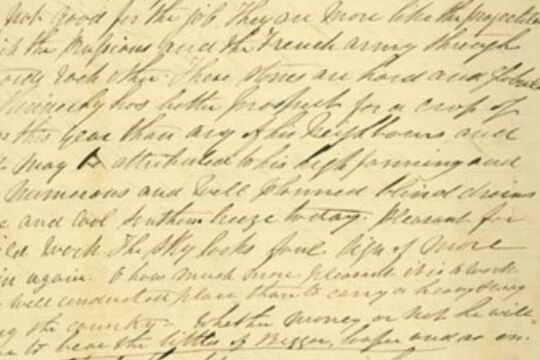

The Welsh Swagman

... prospect for a crop of corn this year than any of his neighbours and that may be attributed to his high farming and his numerous and well planned and blind drains Fine and cool Southern breeze today. Pleasant for field work. The sky looks … sign of more ...Joseph Jenkins was a Welsh itinerant labourer in late 1800s Victoria.

Exceptional for a labourer at the time, Jenkins had a high level of literacy and kept detailed daily diaries for over 25 years, resulting in one of the most comprehensive accounts of early Victorian working life.

Itinerant labourers of the 1800s, or 'swagmen', have become mythologised in Australian cultural memory, and so these diaries provide a wonderful source of information about the life of a 'swagman'. They also provide a record of the properties and districts Jenkins travelled to, particularly around the Castlemaine and Maldon area.

The diaries were only discovered 70 years after Jenkins' death, in an attic, and were in the possession of Jenkins’s descendants in Wales until recently, when they were acquired by the State Library of Victoria in 1997.

-

Collingwood Technical School

... in the Johnston Street site until 2005, when its lifespan as an educational facility ended. The buildings sat empty and in disrepair for more than a decade while the Victorian State Government formulated a renewal plan, including a permanent home for Circus Oz ...For over 140 years, the site of the former Collingwood Technical School on Johnston Street, Melbourne, has played an integral role in the well being of the local community.

It has been a civic hub, including courthouse (1853), Council Chambers (1860) and the Collingwood Artisans’ School of Design (1871). The school opened in 1912 when its first principal, Matthew Richmond, rang a bell on the street to attract new students. Collingwood was a poor and industrial suburb, and as a trade school, young boys were offered the opportunity to gain industrial employment skills.

Throughout the twentieth century, Collingwood Technical School supported the local and broader community. From training schemes for ex-servicemen who were suffering from post traumatic stress following World War I (1914-1918), to extra classes during the Great Depression, and the development of chrome and electroplating for machine parts for the Australian Army and Air Force during World War II (1939-1945).

The precinct between Johnston, Perry and Wellington Streets has transformed over time, including expansion with new buildings and school departments, and the change in the demographic of students as Collingwood evolved from an industrial centre to eventual gentrification. And in 1984, New York street artist, Keith Haring (1958-1990), painted a large mural onsite.

Collingwood Technical College closed in 1987 when it amalgamated with the Preston TAFE (Technical and Further Education) campus. Education classes continued until 2005 and the site sat empty for more than a decade, before a section was redeveloped for Circus Oz in 2013.

The former school now has a new identity as Collingwood Arts Precinct, and is being developed into an independent space for small and medium creative organisations. The heritage buildings will house the next generation of thinkers and makers, and will become a permanent home to the arts in Collingwood. -

Wind & Sky Productions

Wind & Sky ProductionsMany Roads: Stories of the Chinese on the goldfields

In the 1850s tens of thousands of Chinese people flocked to Victoria, joining people from nations around the world who came here chasing the lure of gold.

Fleeing violence, famine and poverty in their homeland Chinese goldseekers sought fortune for their families in the place they called ‘New Gold Mountain’. Chinese gold miners were discriminated against and often shunned by Europeans. Despite this they carved out lives in this strange new land.

The Chinese took many roads to the goldfields. They left markers, gardens, wells and place names, some which still remain in the landscape today. After a punitive tax was laid on ships to Victoria carrying Chinese passengers, ship captains dropped their passengers off in far away ports, leaving Chinese voyagers to walk the long way hundreds of kilometres overland to the goldfields. After 1857 the sea port of Robe in South Australia became the most popular landing point. It’s estimated 17,000 Chinese, mostly men, predominantly from Southern China, walked to Victoria from Robe following over 400kms of tracks.

At the peak migration point of the late 1850s the Chinese made up one in five of the male population in fabled gold mining towns of Victoria such as Ballarat, Bendigo, Castlemaine, Beechworth and Ararat. It was not just miners who took the perilous journey. Doctors, gardeners, artisans and business people voyaged here and contributed to Victoria’s economy, health and cultural life. As the nineteenth century wore on and successful miners and entrepreneurs returned home, the Chinese Victorian population dwindled. However some chose to settle here and Chinese culture, family life, ceremony and work ethic became a distinctive feature of many regional Victorian towns well into the twentieth century.

By the later twentieth century many of the Chinese relics, landscapes and legacy of the goldrush era were hidden or forgotten. Today we are beginning to unearth and celebrate the extent of the Chinese influence in the making of Victoria, which reaches farther back than many have realised.

-

Jary Nemo and Lucinda Horrocks

Jary Nemo and Lucinda HorrocksCollections & Climate Change

The world is changing. Change is a natural part of the Earth’s cycle and of the things that live on it, but what we are seeing now is both like and unlike the shifts we have seen before.

Anthropogenic change, meaning change created by humans, is having an impact on a global scale. In particular, human activity has altered the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere, causing the world’s climate to change.

Already in the state of Victoria we are seeing evidence of this change around us. In the natural world, coastal waters are warming and bringing tropical marine species to our bays. Desert animals are migrating to Victoria. Alpine winters are changing, potentially putting plants and animals at risk of starvation and pushing species closer to the margins. In the world of humans, island and coastal dwellers deal with the tangible and intangible impacts of loss as sea levels rise, bush dwellers live with an increased risk of life-threatening fires, farmers cope with the new normal of longer droughts, and we all face extreme weather events and the impacts of social and economic change.

This Collections and Climate Change digital story explores how Victoria’s scientific and cultural collections help us understand climate change. It focuses on three Victorian institutions - Museums Victoria, the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria and Parks Victoria. It looks at how the information gathered and maintained by a dedicated community of researchers, curators, scientists, specialists and volunteers can help us understand and prepare for a hotter, drier, more inundated world.

The story is made up of a short documentary film and twenty-one examples highlighting how botanical records, geological and biological specimens and living flora and fauna provide a crucial resource for scientists striving to map continuity, variability and change in the natural world. And it helps us rethink the significance of some of Victoria’s cultural collections in the face of a changing climate.