Showing 716 items matching "boning"

-

Wodonga & District Historical Society Inc

Wodonga & District Historical Society IncSouvenir - Souvenir Cup and Saucer Woodland Grove, Wodonga, Victoria, Royal Stafford China, c1940s

This item is from a collection donated by descendants of John Francis Turner of Wodonga. Mr. Turner was born on 6 June 1885. He completed all of his schooling at Scotts Boarding School in Albury, New South Wales. On leaving school, he was employed at Dalgety’s, Albury as an auctioneer. In 1924 John was promoted to Manager of the Wodonga Branch of Dalgety’s. On 15/03/1900 he married Beatrice Neal (born 7/12/1887 and died 7/2/1953) from Collingwood, Victoria. They had 4 daughters – Francis (Nancy), Heather, Jessie and Mary. In 1920, the family moved From Albury to Wodonga, purchasing their family home “Locherbie” at 169 High Street, Wodonga. "Locherbie" still stands in Wodonga in 2022. The collection contains items used by the Turner family during their life in Wodonga. A wide range of small china pieces carrying scenic views of holiday destinations or key locations were a popular kind of souvenir during much of the 20th century. Several different items have been produced to commemorate Wodonga and its landmarks over time. These items document key changes in Wodonga and its heritage. This plate depicts three key landmarks in Wodonga. THE SOLDIERS' MEMORIAL in Wodonga was unveiled on Tuesday 18th November 1924. It was designed by Messrs. Hosken & Co., of Hawthorn, Victoria. The monument is all of Australian workmanship. The pedestal is made of Harcourt granite, 9ft x 9ft at the base, and rising in seven courses to a height of 10ft 2in. The emblems (rising sun and wreath) are of bronze, and the lettering of the inscription and names of fallen soldiers are in raised lead letters. Originally the Memorial was completed with a full life size, 6ft in height, sculpture of an Australian soldier in Sicilian marble. The memorial bore the inscriptions: ERECTED BY THE RESIDENTS OF WODONGA AND DISTRICT IN MEMORY of the Men of this Town and District who fell in the Great War, 1914-1919, Also in grateful recognition of the men who served and returned. “Lest We Forget.” In 1982, due to frequent vandalism and high cost of materials to repair, the soldier statue was removed and later installed at the RSL Rooms. THE WATER TOWER is a major landmark of High Street, Wodonga. It began operation from January 1924 until it ceased operation in 1959. It stood unused for a decade until the lower section was modified and put to use as “ The Tower’s Cobbler’s Inn” in 1962. In 1972 Wodonga City Council proposed to demolish the Tower. Their suggestion received an unfavorable response from the city’s citizens, so the Tower still stands today. THE BAND ROTUNDA was officially opened on Sunday 5th September 1920 at the naming of the triangular reserve at the corner of High and Hovell Streets as Woodland Grove. The Wodonga Band gave a public performance on this occasion. The tri-coloured ribbon, which stretched across the entrance to the Rotunda was cut by Mrs R.H Murphy, daughter of Mr. John Woodland, secretary of the Wodonga Shire Council for 35 years, after whom the area was named. The rotunda has since been moved to Martin Park, Wodonga. This item comes from a collection used by a prominent citizen of Wodonga. It is also representative of a domestic item common in the 1940s and features significant landmarks used in many forms to represent the city of Wodonga.This bone china cup and saucer set features an image of Woodland Grove. Wodonga, Victoria. The image incorporates landmarks in Woodland Grove, including the Soldiers' Memorial, the Rotunda and the Water Tower. There is a makers' mark imprinted on the underside of the plate."ROYAL STAFFORD/BONE CHINA/ MADE IN ENGLAND/ 423" . A crown is in the centre of the textmemorabilia, woodland grove, wodonga victoria -

Stawell Historical Society Inc

Stawell Historical Society IncPhotograph, 2 Black & White photos of Annie Elizabeth Bone Family

Photo of Annie Elizabeth Bone born 22.8.1873 died 25.10.1937. Photo taken Herbert's Studio StawellHerbert's Studio Stawell photographBlack and white portrait photo of Annie Elizabeth Bone in a seated position. The dress has with frills around the neck and shoulders.Herbert's Studio Stawellstawell portrait -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Rib Bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale rib bone with advanced stage of calcification as indicated by brittleness. None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RANZCOG)

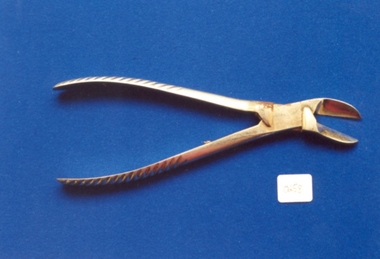

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RANZCOG)Ferguson's bone cutter used by Dr Lorna Lloyd-Green

In the 1950s and 60s, Ferguson's bone cutters were used by obstetricians to remove the foreskin during circumcisions. The scoring on the handles is to prevent the tool slipping in the user's grip when in use.Metal bone cutter, with hand grip scoring on outer arms. Similar in appearance to pliers, with short cutting blades.circumcision -

Tatura Irrigation & Wartime Camps Museum

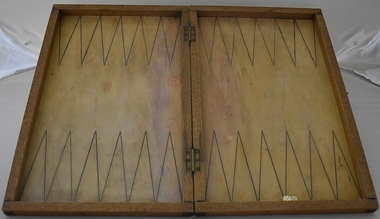

Tatura Irrigation & Wartime Camps MuseumLeisure object - board game, Backgammon, 1940's

Made by German internee from Palestine held in Camp 3. The dice are made from bone from the kitchen.Rectangular wooden board game, hinged in centre. Base is marked for playing a game of backgammon. Handmade. Pair of dice made from kitchen bone.toys, camp 3 entertainment, dice, backgammon board -

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural Collection

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural CollectionSouvenir - Souvenir Cup - Portland Victoria, n.d

Identifying numbers: 5873 a, b White, fine bone china cup and saucer. Image of Loreto Convent and All Saints Church on both cup and saucer. Made in England.Front: 'View at Portland Vic' Back: Maker's stamp and crest - 'Royal Stafford Guaranteed English Bone China Made in England'city of portland, portland victoria -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070. Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone piece. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.Noneflagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Vertebrae, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Whalebone The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The bone of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as whalebone. Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale bone Vertebrae with advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural Collection

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural CollectionSouvenir - Souvenir Saucer - Portland Victoria, n.d

Identifying numbers: 5873 a, b White, fine bone china saucer. (Part of a cup and saucer set) Image of Loreto Convent and All Saints Church on both cup and saucer. Made in England.Front: 'View at Portland Vic' Back: Maker's stamp and crest - 'Royal Stafford Guaranteed English Bone China Made in England'city of portland, portland victoria -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined