Showing 47 items matching "wall telephone"

-

National Communication Museum

National Communication MuseumEquipment - Ericofon, Ericsson, 1950s

The Ericofon was the first commercially successful telephone which incorporated both handle and dial within a single unit. Manufactured by the Swedish company Ericsson, and available for lease from the Postmaster-General’s Department, the streamlined design has been praised for anticipating the cordless phone, and later mobile phone, by several decades. The ‘cobra’ design was formulated in the 1940s and manufactured in the 1950s; Australian cases were likely made in the L M Ericsson Broadmeadows factory. Although new thermoplastic technology allowed for a bolder aesthetic than traditional black Bakelite telephones, Ericofon sales accounted for only 4% of the market and it never enjoyed popularity with Australian subscribers. The design did, however, spark a conceptual shift whereby the telephone “was seen more as a consumer product than merely an extension of telephony” (Ericsson).Clear plastic telephone casing inside which are coloured electrical wires. Telephone has a broad base that contains the dial, mouthpiece and cord with cream plastic coated wall plug attached at rear. Handle tapers in a curve to a stylised squared earpiece. Dial underneath is a rotary dial with red disconnection button in the centre. telephone, design, domestic, ericsson, industrial design -

Vision Australia

Vision AustraliaPhotograph - Image, RBS workers with Opticons

1. Male sits at a desk with a Wang computer terminal in front of him and Optacon device to his left. The Optacon was a device that allowed printed material to be turned into Braille through the use of a small camera connected to a vibrating array that produced the Braille. To his right is a cassette recorder, another computer and recorder, whilst a long cane rests against a wall. The man is possibly wearing a sonic guide and listening to the cassette whilst he types on to the screen. 2. Male sits in an office with an Opticon to his left, which he is using, and a manual typewriter in front of him. The typewriter has the camera of the Opticon clamped into position over the typewriter. Behind the man is a reception desk, with a bell and small switchboard visible on upper counter of the desk, and a coffee mug, portable cassette recorder, telephone books and piles of paper stacked neatly under the upper counter.Digital image taken from pictures on chipboard15 - Group with 13, 14 please - no caption available 12 - Group with 13, Optacon captionemployment, royal blind society of new south wales -

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)

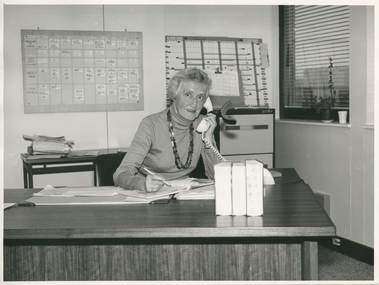

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)Photograph - Photograph, black and white, 09 05 1967

This Sister is working at the Control Centre at RDNS Headquarters, 452 St. Kilda Road, Melbourne where she is receiving a phone call which she will transfer to the appropriate staff member in Headquarters, or if appropriate pass the message onto an RDNS Centre to take action. Central Control was based in the Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS), Headquarters and the Sister working there took and directed all incoming telephone calls to persons in Headquarters or to the appropriate RDNS Centre. Each Centre contacted the Control Sister each morning for any messages received over night. She remained in contact with each RDNS Centre during the day, and in contact with Evening staff after each Centre was closed at 6 p.m. Evening staff contacted Central Control after completing their evening visits, and book work, so the Sister in Central Control knew they were safe and had completed their shift before leaving the RDNS premises. Of a weekend, when reduced staff numbers were working, the same procedure was carried out by the Sister working in each Center's office. In the centre of this black and white photograph is a Royal District Nursing Service, (RDNS), Sister, who wears glasses and has short curly hair, is wearing a watch on her left wrist and is wearing her grey short sleeved uniform with an RDNS cotton badge applied to the top of the sleeve. She is sitting behind a desk and is holding a telephone to her right ear; she has a pen in her left hand and is ready to write in an open white paged book. A typewriter is on the left hand side of the desk and a black telephone can be seen on a shelf adjacent to the desk, A framed rectangular mirror can be seen on the left hand side wall. A shelf, with several books on the left hand side, can be seen attached to the upper part of the wall behind the Sister. Below this a large chart is on the wall and a wooden shelf below itPhotographers Stamp. 'Quote No. GE 14rdns, royal district nursing service, rdns administration -

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)Photograph - Photograph, black and white, Barry Sutton, 24.06.1971

This photograph is taken in Footscray Centre and Sister Ellen Anderson is the Supervisor of this Centre. Mrs. Hogan is the Clerical Officer working at Footscray and discusses any phone calls received with Sister Anderson.Gradually over the years, Melbourne District Nursing Service (MDNS), later known as Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS), from 1966 when they received Royal patronage, opened Centres throughout the Melbourne Metropolitan area. Their trained nurses (Sisters) left from these Centres each morning to carry out their nursing visits in a specific area, taking any sterilized equipment needed with them. They returned at the end of the day to write up their patients nursing histories, clean and reset any equipment used ready for sterilization, and contact other medical and community personal as necessary. Most of the RDNS cars were housed at each Centre, only a few being driven home by a Sister. Clerical staff worked in each Centre.Black and white photograph of Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS) Sister Anderson and Mrs. Hogan in the office at Footscray Centre. Mrs. Hogan, on the left hand side of the photograph, is wearing glasses; has short dark hair and is wearing a dark coloured dress. She is holding a sheet of white paper in her right hand and is holding a telephone to her ear with her left hand. She is turned sideways on the chair at a desk and is facing Sister Anderson on her right. Sister Anderson has short dark curly hair and is wearing her RDNS grey long sleeve uniform dress with a pen in her left upper pocket. She is sitting at a desk; which has a large blotter and an open page calendar on it, and is holding an open folder. She is looking at Mrs. Hogan. Part of a typewriter on Mrs Hogan's desk, can be seen in the left foreground. A small telephone switchboard with telephone books on it, can be seen in the left background. Above this is a rectangular dark coloured board with hooks and some keys on it is attached to the rear wall. To the right of this is a large black rectangular board with the heading "Royal District Nursing Service Footscray Centre". This is marked off in sections and shows "The Daily Visits". Part of some windows can be seen above this.Photographer stamp. Quote No. 11 Aroyal district nursing service, rdns, rdns centre, mrs hogan, sister ellen anderson -

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)

Royal District Nursing Service (now known as Bolton Clarke)Photograph - Photograph, black and white, Barry Sutton, c.1970

Miss Wright is Director of Education at Royal District Nursing Service (RDNS). She is sitting at a desk in the Education Department which was in Headquarters, 452 St. Kilda Road, until 1974 when it relocated to larger premises at 448 St. Kilda Road. Education was an integral part of Melbourne District Nursing Society (MDNS) from its inception in 1885, later called Royal District Nursing Service, (RDNS). Only Trained Nurses (Nurses) were employed by the Society, and on visits to patients they taught the necessity of hygiene and cleanliness, as well as the need for a good diet, to bring about good health. Doctor’s lectures were later given at the MDNS home to instruct patients and their families on prevention of disease. Education to patients continued throughout the years regarding health care and the use of equipment in the home. In 1961 Education programs commenced at MDNS with their Trained nurses (Sisters) receiving In-service education. Staff could also apply for scholarships to further their education outside of RDNS. At RDNS many programs were run, including: a Post Basic Course, Cardiac Rehabilitation Nursing, Haematology/Oncology Nursing, Palliative Care program, Diabetic Stabilization Program, Leg Ulcer Management Program, Wound Care Specialist Program, HIV/AIDS Nursing Care, Cystic Fibrosis Home Support, Veterans Home Care Program, Homeless persons Program, Breast Cancer Support Program, Continence Management Program, Stomal Therapy Program, In-Home Lactation Support Program. RDNS staff attended several hospitals to observe and learn special care needed to some clients, e.g. to the Austin Hospital to learn the care required for paraplegic and quadriplegic clients at home and to Mount Royal Hospital to observe the care of clients in the rehabilitation ward.. A Community Nursing Education Program was extended to student nurses from hospitals and to other nursing organizations. These Education programs kept the RDNS Sisters abreast of new techniques, such as changes in technology for e.g. new testing methods in detecting glucose levels in Diabetic patients. Sr. Nan Deakin obtained a Post Basic Certificate in Psychiatric Nursing and included this area in her education lectures. Sr. Daphne Geldard specialized in the area of Alzheimer’s disease and Dementia. These Sisters visited patients in District areas with the regular RDNS Sister when required. Every member of staff, both professional and non professional staff, received regular education in the Education Department. In 1980, a Home Health Aide pilot study, funded by the Federal Government, the Brotherhood of St. Laurence and RDNS, with the program written and taught by Sr. Rowley, was evaluated as successful, and Home Health Aides were employed and worked in RDNS Centres under the supervision of the RDNS Sisters. Black and white photograph of Miss Ora Wright, who has light coloured wavy hair and is wearing a grey long sleeve top with a long string of mixed coloured beads hanging over it. She is sitting behind a dark coloured wooden desk and has a pen in her right hand poised to write on a white sheet of paper. Her left arm is bent with her hand holding the light coloured hand-piece of a telephone to her left ear. There is a large blotter and other sheets of white paper on the desk as well as three thick books standing on the front right hand side of the desk. Behind her to the right is a two drawer filing cabinets and above this is a large board with charts running down it. On the left hand side of the photograph a low table with papers stacked on it. Above this, attached to the wall, is a rectangular board with horizontal and vertical rows marked out and some white cards on it. On the far right of the photograph, part of a wall and open Venetian blinds over a window can be seen.Photographer stamp and Quote No. DR 2royal district nursing service, rdns, rdns education, ora wright, -

Parks Victoria - Cape Nelson Lightstation

Parks Victoria - Cape Nelson LightstationFunctional object - Telephones

... Five similar intercom system telephones. All are wall...-road Each of the five telephones is attached to a timber, wall ...Each of the five telephones is attached to a timber, wall‐mounted box. They are original to the precinct buildings and date from the early twentieth century. Located in the lighthouse lantern room, the former head keeper’s quarters, the former assistants’ quarters, and the buildings known today as the generator shed and the café, they formed an intercom system that facilitated communication between the lightstation buildings.Wall‐mounted Bakelite telephones with crank handles can be found at all six light stations, however Gabo Island has the only other example of a timber‐mounted phone. Its design is slightly different for incorporating an inclined surface for jotting down notes. As fixtures, the telephones are considered to be part of the building fabric and included in the Victorian Heritage Register listing for the Cape Nelson Lightstation (H1773; 18 February 1999). They are historically significant for their historical and technical values as part of the early communications system used at the lightstation.Five similar intercom system telephones. All are wall mounted timber boxes with Bakelite black hand sets and black cords. The five phones each have two bells at the top of the box and a crank handle at the side. Three phones have brass bells, two have black metal bells. All phones have instructions on the front either in a frame or glued to the timber."C of A" and "PMG" Written instructions on how to use the phones are printed on paper fixed to the front of the telephones. "TO CALL ....../ TO ANSWER...../ WHEN FINISHED....." -

Parks Victoria - Cape Nelson Lightstation

Parks Victoria - Cape Nelson LightstationFurniture - Cabinet

The cabinet has a curved back and would have been custom‐built to fit the dimensions of the lantern room interior. It is likely to date from when the lighthouse was built in 1884 and may have been among the items delivered by the government steamer dispatch early in March which included ‘the lantern and other fittings for the Cape Nelson Lighthouse’. The Public Works Department provided a range of lightstation furnishings including office desks and cabinets, and domestic settings for keepers’ quarters, with nineteenth century items often stamped with a crown motif and the PWD monogram however the curved cupboards installed in Victoria’s lighthouse lantern rooms do not appear to display this small feature. Further research may reveal more about their manufacture and it is tempting to think that they were perhaps even supplied by Chance Bros as part of the entire lantern room installation. The company usually provided the timber battens for the lantern room paneling, and a cabinet may have been included in the assemblage. Another possibility is that the specially designed cabinet was made on site by carpenters along with other fittings. It is not known whether it is attached to the wall or movable; if attached it is considered to be a fixture and included in the Victorian Heritage Register listing for the lightstation (VHR H1773). Its location, when identified in the CMP of April 1995, was on the ‘lower lantern level’, where there was also a ‘timber step ladder’ (Argus, 6 March 1884, p6. nineteenth or early twentieth century), ‘timber framed lighthouse specification’, ‘timber framed chart’ and telephone .Residue on the furnishing indicates that it was formerly painted green, the colour of some of the other fixtures in the room, such as the original cast iron ladder. It is now partially varnished and the corner to the top’s edging on the right side has been cut off. The lighthouse also has a large curved back, two‐door cupboard. Other similar cabinets with curved backs survive at Cape Schanck, varnished wood cabinet with brass door knob, no drawers; Point Hicks, painted green with silver doors, no drawers and Gabo Island, bench top, 2‐door, no drawers, green paint removed to reveal cedar timber). Cape Nelson’s curved cabinet is unique among these examples for having drawers. The cabinet is a unique, original feature of the lantern room and has first level contributory significance for its historic values and provenance.The bench top cupboard has two drawers, each above a door, and each door is framed and beveled around a central panel. The cabinet has a curved back. -

Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (FCRPA)

Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (FCRPA)Telescope used in FCV fire towers - ex military, c 1940s

Victoria once had well over one hundred fire lookouts and firetowers. Fire lookouts, or observation posts, were often just a clearing on a hill or a vantage point, whereas firetowers were definite structures. Many were established by the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) in the 1920s, but the network was expanded rapidly in response to recommendations of the Stretton Royal Commission after the 1939 Black Friday bushfires. When a fire or smoke was spotted from the tower a bearing was taken with the alidade and radioed or telephoned into the district office. It was then cross referenced with bearings from other towers on a large wall map to give a "fix" on the fire location Alidades and telescopes were used in the post war period but were replaced with a much simpler map table and reference string suspended from the centre of the tower cabin.Uncommon usageTelescope used in fire towers Ex military Kern Company NY Argus made in USA Adjustment lens, dials and focus ring Small spirit levelbushfire, forests commission victoria (fcv) -

Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (FCRPA)

Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (FCRPA)Alidade - sight tube used in FCV fire towers, c 1940s

Victoria once had well over one hundred fire lookouts and firetowers. Fire lookouts, or observation posts, were often just a clearing on a hill or a vantage point, whereas firetowers were definite structures. Many were established by the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) in the 1920s, but the network was expanded rapidly in response to recommendations of the Stretton Royal Commission after the 1939 Black Friday bushfires. When a fire or smoke was spotted from the tower a bearing was taken with the alidade and radioed or telephoned into the district office. It was then cross referenced with bearings from other towers on a large wall map to give a "fix" on the fire location Alidades and telescopes were used in the post war period but were replaced with a much simpler map table and reference string suspended from the centre of the tower cabin.Uncommon usageAlidade Sight TubeFCV and bearing markers on the alloy base. Very simple design. bushfire, forests commission victoria (fcv) -

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate ActionFire Finder

Victoria once had well over one hundred fire lookouts and firetowers. Fire lookouts, or observation posts, were often just a clearing on a hill or a vantage point, whereas firetowers were definite structures. Many were established by the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) in the 1920s, but the network was expanded rapidly in response to recommendations of the Stretton Royal Commission after the 1939 Black Friday bushfires. When a fire or smoke was spotted from the tower a bearing was taken with the alidade and radioed or telephoned into the district office. It was then cross referenced with bearings from other towers on a large wall map to give a "fix" on the fire location. Alidades and telescopes were used in the post war period but were replaced with a much simpler map table and reference string suspended from the centre of the tower cabin. This "Fire Finder" was used in Canadian fire towers to identify the location of wildfires. The unique design was first developed by the British Columbia Forest Service (BCFS) in the early 1950s. Close examination of the map indicates that this particular Fire Finder may have been once used at Bluejoint Mountain lookout in Granby Provincial Park. This Fire Finder was a gift to Barry (Rocky) Marsden from the British Columbia Forest Service in the late 1980s in recognition of the close relationships that had been forged with the staff at the Altona Workshops over many decades. Fire Finders were originally painted black but this one was repainted green after it arrived at Altona. The BC Forest Service had a large facility where they manufactured Fire Finders and many other items of equipment, but in the 1980s it was shut down. Heavy cast iron circular object with a paper topographic map mounted on it. The metal dial and ruler works similar to a compass. The sight tube is used to determine the bearing and elevation of the fire on the map. This Fire Finder also sometimes known as an Alidade. Its a different design from the Osborne Fire Finder widely used in North American fire lookouts from the 1920s. British Columbia Forest Service. Model 62A. Serial Number 6308.bushfire -

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate ActionFire Finder

Victoria once had well over one hundred fire lookouts and firetowers. Fire lookouts, or observation posts, were often just a clearing on a hill or a vantage point, whereas firetowers were definite structures. Many were established by the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) in the 1920s, but the network was expanded rapidly in response to recommendations of the Stretton Royal Commission after the 1939 Black Friday bushfires. When a fire or smoke was spotted from the tower a bearing was taken with the alidade and radioed or telephoned into the district office. It was then cross referenced with bearings from other towers on a large wall map to give a "fix" on the fire location. Alidades and telescopes were used in the post war period but were replaced with a much simpler map table and reference string suspended from the centre of the tower cabin. This "Fire Finder" was used in Canadian fire towers to identify the location of wildfires. The unique design was first developed by the British Columbia Forest Service (BCFS) in the early 1950s. Close examination of the map indicates that this particular Fire Finder may have been once used at Bluejoint Mountain lookout in Granby Provincial Park. This Fire Finder was a gift to Barry (Rocky) Marsden from the British Columbia Forest Service in the late 1980s in recognition of the close relationships that had been forged with the staff at the Altona Workshops over many decades. Fire Finders were originally painted black but this one was repainted green after it arrived at Altona. The BC Forest Service had a large facility where they manufactured Fire Finders and many other items of equipment, but in the 1980s it was shut down. Heavy cast iron circular object with a paper topographic map mounted on it. The metal dial and ruler works similar to a compass. The sight tube is used to determine the bearing and elevation of the fire on the map. This Fire Finder also sometimes known as an Alidade. Its a different design from the Osborne Fire Finder widely used in North American fire lookouts from the 1920s. British Columbia Forest Service. Model 62A. Serial Number 6308.bushfire -

Eltham District Historical Society Inc

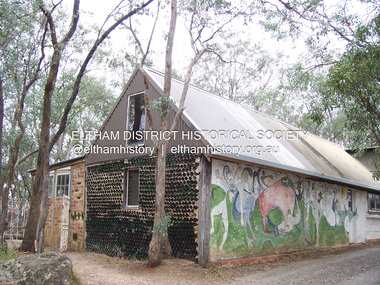

Eltham District Historical Society IncPhotograph - Digital Photograph, Marguerite Marshall, Art Gallery at Clifton Pugh's Artists' Colony, Dunmoochin, Barreenong Road, Cottles Bridge, 5 February 2008

Art Gallery with mural painted by Clifton Pugh (1924-1990) at his Artists' Colony, Dunmoochin, Barreenong Road, Cottles Bridge. Following military service in the second world war, Clifton Pugh studied under artist Sir William Dargie at the National Gallery School in Melbourne as well as Justus Jorgensen, founder of Montsalvat. For a while he lived on the dole but also worked packing eggs for the Belot family saving sufficient to purchase six acres (2.4 ha) of land at Barreenong Road, Cottles Bridge. He accumulated more land and persuaded several other artists and friends to buy land nearby, resulting in a property of approximately 200 acres, stablishing it as one of the first artistic communes in Australia alongside Montsalvat in Eltham. It was around 1951 that Pugh felt he had '"done moochin' around" and so the name of the property evolved. He bought timber from Alistair Knox to build his house on the crest of a hill. Inspired by local goldminer's huts, it was a one room wattle-and-daub structure with dirt floor. Over the years it expanded with thick adobe walls made from local clay, high ceilings and stone floors. All materials other than the local earth were sourced from second hand materials, most found at wreckers' yards. Artists from across the nation were drawn to Dunmoochin, with several setting up houses and shacks on the property, maintaining their independence but sharing their artistic zeal. Artists who worked or resided at Dunmoochin included Mirka Mora, John Perceval, Albert Tucker, Fred Williams, Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd and John Olsen. In 2002, Pugh's house along with its treasure trove of art and a library of some 20,000 books was destroyed by fire. Traces of Pugh's home remain with the presence of the Victorian doorframe archway with leadlight of intricate design, procured from a demolished Melbourne mansion; and two bronze life-sized female statues created by Pugh and cast by Matcham Skipper. In place of Pugh's house rose two double-storey mud-brick artists' studios topped with corrugated iron rooves curved like the wings of a bird with accommodation for seven. The original studios, gallery and other buildings survived the fire. Covered under Heritage Overlay, Nillumbik Planning Scheme. Published: Nillumbik Now and Then / Marguerite Marshall 2008; photographs Alan King with Marguerite Marshall.; p153 It’s not surprising that artist Clifton Pugh was drawn to Cottles Bridge to establish his artists’ colony Dunmoochin. Undisturbed by the clamour of modern life at Barreenong Road, Pugh was surrounded by the Australian bush he loved, and where his ashes were later scattered. The 200 acres (81ha) of bushland, broken by glimpses of rolling hills, has more than 50 species of orchids and Pugh shared his property with native animals including kangaroos, emus, phascogales, wombats, and diverse bird life. Pugh encouraged these creatures to join him in the bush by creating, with Monash University, a holding station where the animals were raised. Dunmoochin inspired Pugh for such paintings as in a book on orchids and the Death of a Wombat series.1 But his love for the bush was accompanied by the fear that Europeans were destroying it and much of his painting illustrated this fear and his plea for its conservation.2 However it was his house rather than the surrounding bush that was to be destroyed. Tragically in 2002 Pugh’s house, with its treasure of art and library of 20,000 art books, was destroyed by fire. Traces of the beauty of Pugh’s home still remain, however, in the magnificent Victorian doorframe archway with leadlight of intricate design procured from a demolished Melbourne mansion; and two bronze life-sized female statues created by Pugh and cast by Matcham Skipper. Now in place of Pugh’s house, are two double-storey mud-brick artists’ studios topped with corrugated roofs curved like birds’ wings, with accommodation for seven. The original studios, gallery and other buildings remain.3 Pugh grew up on his parents’ hobby farm at Briar Hill and attended the Briar Hill Primary School, then Eltham High School and later Ivanhoe Grammar. At 15 he became a copy boy for the Radio Times newspaper, then worked as a junior in a drafting office. Pugh was to have three wives and two sons. After serving in World War Two in New Guinea and Japan, Pugh studied under artist Sir William Dargie, at the National Gallery School in Melbourne.4 Another of his teachers was Justus Jörgensen, founder of Montsalvat the Eltham Artists’ Colony. Pugh lived on the dole for a while and paid for his first six acres (2.4ha) at Barreenong Road by working as an egg packer for the Belot family. Pugh accumulated more land and persuaded several other artists and friends to buy land nearby, resulting in the 200 acre property. They, too, purchased their land from the Belot family by working with their chickens. Around 1951 Pugh felt he had ‘Done moochin’ around’ and so the name of his property was born. Pugh bought some used timber from architect Alistair Knox to build his house on the crest of a hill. Inspired by local goldminers’ huts it was a one-room wattle-and-daub structure with a dirt floor. It was so small that the only room he could find for his telephone was on the fork of a tree nearby.5 Over the years the mud-brick house grew to 120 squares in the style now synonymous with Eltham. It had thick adobe walls (sun-dried bricks) made from local clay, high ceilings and stone floors with the entire structure made of second-hand materials – most found at wreckers’ yards. Pugh’s first major show in Melbourne in 1957, established him as a distinctive new painter, breaking away from the European tradition ‘yet not closely allied to any particular school of Australian painting’.6 Pugh became internationally known and was awarded the Order of Australia. He won the Archibald Prize for portraiture three times, although he preferred painting the bush and native animals. In 1990 not long before he died, Pugh was named the Australian War Memorial’s official artist at the 75th anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli. Today one of Pugh’s legacies is the Dunmoochin Foundation, which gives seven individual artists or couples and environmental researchers the chance to work in beautiful and peaceful surroundings, usually for a year. By November 2007, more than 80 people had taken part, and the first disabled artist had been chosen to reside in a new studio with disabled access.1 In 1989, not long before Pugh died in 1990 of a heart attack at age 65, he established the Foundation with La Trobe University and the Victorian Conservation Trust now the Trust for Nature. Pugh’s gift to the Australian people – of around 14 hectares of bushland and buildings and about 550 art works – is run by a voluntary board of directors, headed by one of his sons, Shane Pugh. La Trobe University in Victoria stores and curates the art collection and organises its exhibition around Australia.2 The Foundation aims to protect and foster the natural environment and to provide residences, studios and community art facilities at a minimal cost for artists and environmental researchers. They reside at the non-profit organisation for a year at minimal cost. The buildings, some decorated with murals painted by Pugh and including a gallery, were constructed by Pugh, family and friends, with recycled as well as new materials and mud-bricks. The Foundation is inspired by the tradition begun by the Dunmoochin Artists’ Cooperative which formed in the late 1950s as one of the first artistic communes in Australia. Members bought the land collaboratively and built the seven dwellings so that none could overlook another. But, in the late 1960s, the land was split into private land holdings, which ended the cooperative. Dunmoochin attracted visits from the famous artists of the day including guitarists John Williams and Segovia; singer and comedian Rolf Harris; comedian Barry Humphries; and artists Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd and Mirka Mora. A potters’ community, started by Peter and Helen Laycock with Alma Shanahan, held monthly exhibitions in the 1960s, attracting local, interstate and international visitors – with up to 500 attending at a time.3 Most artists sold their properties and moved away. But two of the original artists remained into the new millennium as did relative newcomer Heja Chong who built on Pugh’s property (now owned by the Dunmoochin Foundation). In 1984 Chong brought the 1000-year-old Japanese Bizan pottery method to Dunmoochin. She helped build (with potters from all over Australia) the distinctive Bizan-style kiln, which fires pottery from eight to 14 days in pine timber, to produce the Bizan unglazed and simple subdued style. The kiln, which is rare in Australia, is very large with adjoining interconnected ovens of different sizes, providing different temperatures and firing conditions. Frank Werther, who befriended Pugh as a fellow student at the National Gallery Art School in Melbourne, built his house off Barreenong Road in 1954. Werther is a painter of the abstract and colourist style and taught art for about 30 years. Like so many in the post-war years in Eltham Shire, as it was called then, Werther built his home in stages using mud-brick and second-hand materials. The L-shaped house is single-storey but two-storey in parts with a corrugated-iron pitched roof. The waterhole used by the Werthers for their water supply is thought to be a former goldmining shaft.4 Alma Shanahan at Barreenong Road was the first to join Pugh around 1953. They also met at the National Gallery Art School and Shanahan at first visited each weekend to work, mainly making mud-bricks. She shared Pugh’s love for the bush, but when their love affair ended, she designed and built her own house a few hundred yards (metres) away. The mud-brick and timber residence, made in stages with local materials, is rectangular, single-storey with a corrugated-iron roof. As a potter, Shanahan did not originally qualify as an official Cooperative member.This collection of almost 130 photos about places and people within the Shire of Nillumbik, an urban and rural municipality in Melbourne's north, contributes to an understanding of the history of the Shire. Published in 2008 immediately prior to the Black Saturday bushfires of February 7, 2009, it documents sites that were impacted, and in some cases destroyed by the fires. It includes photographs taken especially for the publication, creating a unique time capsule representing the Shire in the early 21st century. It remains the most recent comprehenesive publication devoted to the Shire's history connecting local residents to the past. nillumbik now and then (marshall-king) collection, art gallery, clifton pugh, dunmoochin, cottlesbridge, cottles bridge, barreenong road -

Eltham District Historical Society Inc

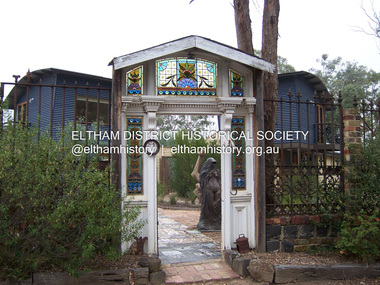

Eltham District Historical Society IncPhotograph - Digital Photograph, Marguerite Marshall, Doorway of Clifton Pugh's former house at Dunmoochin, Barreenong Road, Cottles Bridge, 5 February 2008

Following military service in the second world war, Clifton Pugh studied under artist Sir William Dargie at the National Gallery School in Melbourne as well as Justus Jorgensen, founder of Montsalvat. For a while he lived on the dole but also worked packing eggs for the Belot family saving sufficient to purchase six acres (2.4 ha) of land at Barreenong Road, Cottles Bridge. He accumulated more land and persuaded several other artists and friends to buy land nearby, resulting in a property of approximately 200 acres, stablishing it as one of the first artistic communes in Australia alongside Montsalvat in Eltham. It was around 1951 that Pugh felt he had '"done moochin' around" and so the name of the property evolved. He bought timber from Alistair Knox to build his house on the crest of a hill. Inspired by local goldminer's huts, it was a one room wattle-and-daub structure with dirt floor. Over the years it expanded with thick adobe walls made from local clay, high ceilings and stone floors. All materials other than the local earth were sourced from second hand materials, most found at wreckers' yards. Artists from across the nation were drawn to Dunmoochin, with several setting up houses and shacks on the property, maintaining their independence but sharing their artistic zeal. Artists who worked or resided at Dunmoochin included Mirka Mora, John Perceval, Albert Tucker, Fred Williams, Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd and John Olsen. In 2002, Pugh's house along with its treasure trove of art and a library of some 20,000 books was destroyed by fire. Traces of Pugh's home remain with the presence of the Victorian doorframe archway with leadlight of intricate design, procured from a demolished Melbourne mansion; and two bronze life-sized female statues created by Pugh and cast by Matcham Skipper. In place of Pugh's house rose two double-storey mud-brick artists' studios topped with corrugated iron rooves curved like the wings of a bird with accommodation for seven. The original studios, gallery and other buildings survived the fire. Covered under Heritage Overlay, Nillumbik Planning Scheme. Published: Nillumbik Now and Then / Marguerite Marshall 2008; photographs Alan King with Marguerite Marshall.; p155 It’s not surprising that artist Clifton Pugh was drawn to Cottles Bridge to establish his artists’ colony Dunmoochin. Undisturbed by the clamour of modern life at Barreenong Road, Pugh was surrounded by the Australian bush he loved, and where his ashes were later scattered. The 200 acres (81ha) of bushland, broken by glimpses of rolling hills, has more than 50 species of orchids and Pugh shared his property with native animals including kangaroos, emus, phascogales, wombats, and diverse bird life. Pugh encouraged these creatures to join him in the bush by creating, with Monash University, a holding station where the animals were raised. Dunmoochin inspired Pugh for such paintings as in a book on orchids and the Death of a Wombat series.1 But his love for the bush was accompanied by the fear that Europeans were destroying it and much of his painting illustrated this fear and his plea for its conservation.2 However it was his house rather than the surrounding bush that was to be destroyed. Tragically in 2002 Pugh’s house, with its treasure of art and library of 20,000 art books, was destroyed by fire. Traces of the beauty of Pugh’s home still remain, however, in the magnificent Victorian doorframe archway with leadlight of intricate design procured from a demolished Melbourne mansion; and two bronze life-sized female statues created by Pugh and cast by Matcham Skipper. Now in place of Pugh’s house, are two double-storey mud-brick artists’ studios topped with corrugated roofs curved like birds’ wings, with accommodation for seven. The original studios, gallery and other buildings remain.3 Pugh grew up on his parents’ hobby farm at Briar Hill and attended the Briar Hill Primary School, then Eltham High School and later Ivanhoe Grammar. At 15 he became a copy boy for the Radio Times newspaper, then worked as a junior in a drafting office. Pugh was to have three wives and two sons. After serving in World War Two in New Guinea and Japan, Pugh studied under artist Sir William Dargie, at the National Gallery School in Melbourne.4 Another of his teachers was Justus Jörgensen, founder of Montsalvat the Eltham Artists’ Colony. Pugh lived on the dole for a while and paid for his first six acres (2.4ha) at Barreenong Road by working as an egg packer for the Belot family. Pugh accumulated more land and persuaded several other artists and friends to buy land nearby, resulting in the 200 acre property. They, too, purchased their land from the Belot family by working with their chickens. Around 1951 Pugh felt he had ‘Done moochin’ around’ and so the name of his property was born. Pugh bought some used timber from architect Alistair Knox to build his house on the crest of a hill. Inspired by local goldminers’ huts it was a one-room wattle-and-daub structure with a dirt floor. It was so small that the only room he could find for his telephone was on the fork of a tree nearby.5 Over the years the mud-brick house grew to 120 squares in the style now synonymous with Eltham. It had thick adobe walls (sun-dried bricks) made from local clay, high ceilings and stone floors with the entire structure made of second-hand materials – most found at wreckers’ yards. Pugh’s first major show in Melbourne in 1957, established him as a distinctive new painter, breaking away from the European tradition ‘yet not closely allied to any particular school of Australian painting’.6 Pugh became internationally known and was awarded the Order of Australia. He won the Archibald Prize for portraiture three times, although he preferred painting the bush and native animals. In 1990 not long before he died, Pugh was named the Australian War Memorial’s official artist at the 75th anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli. Today one of Pugh’s legacies is the Dunmoochin Foundation, which gives seven individual artists or couples and environmental researchers the chance to work in beautiful and peaceful surroundings, usually for a year. By November 2007, more than 80 people had taken part, and the first disabled artist had been chosen to reside in a new studio with disabled access.1 In 1989, not long before Pugh died in 1990 of a heart attack at age 65, he established the Foundation with La Trobe University and the Victorian Conservation Trust now the Trust for Nature. Pugh’s gift to the Australian people – of around 14 hectares of bushland and buildings and about 550 art works – is run by a voluntary board of directors, headed by one of his sons, Shane Pugh. La Trobe University in Victoria stores and curates the art collection and organises its exhibition around Australia.2 The Foundation aims to protect and foster the natural environment and to provide residences, studios and community art facilities at a minimal cost for artists and environmental researchers. They reside at the non-profit organisation for a year at minimal cost. The buildings, some decorated with murals painted by Pugh and including a gallery, were constructed by Pugh, family and friends, with recycled as well as new materials and mud-bricks. The Foundation is inspired by the tradition begun by the Dunmoochin Artists’ Cooperative which formed in the late 1950s as one of the first artistic communes in Australia. Members bought the land collaboratively and built the seven dwellings so that none could overlook another. But, in the late 1960s, the land was split into private land holdings, which ended the cooperative. Dunmoochin attracted visits from the famous artists of the day including guitarists John Williams and Segovia; singer and comedian Rolf Harris; comedian Barry Humphries; and artists Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd and Mirka Mora. A potters’ community, started by Peter and Helen Laycock with Alma Shanahan, held monthly exhibitions in the 1960s, attracting local, interstate and international visitors – with up to 500 attending at a time.3 Most artists sold their properties and moved away. But two of the original artists remained into the new millennium as did relative newcomer Heja Chong who built on Pugh’s property (now owned by the Dunmoochin Foundation). In 1984 Chong brought the 1000-year-old Japanese Bizan pottery method to Dunmoochin. She helped build (with potters from all over Australia) the distinctive Bizan-style kiln, which fires pottery from eight to 14 days in pine timber, to produce the Bizan unglazed and simple subdued style. The kiln, which is rare in Australia, is very large with adjoining interconnected ovens of different sizes, providing different temperatures and firing conditions. Frank Werther, who befriended Pugh as a fellow student at the National Gallery Art School in Melbourne, built his house off Barreenong Road in 1954. Werther is a painter of the abstract and colourist style and taught art for about 30 years. Like so many in the post-war years in Eltham Shire, as it was called then, Werther built his home in stages using mud-brick and second-hand materials. The L-shaped house is single-storey but two-storey in parts with a corrugated-iron pitched roof. The waterhole used by the Werthers for their water supply is thought to be a former goldmining shaft.4 Alma Shanahan at Barreenong Road was the first to join Pugh around 1953. They also met at the National Gallery Art School and Shanahan at first visited each weekend to work, mainly making mud-bricks. She shared Pugh’s love for the bush, but when their love affair ended, she designed and built her own house a few hundred yards (metres) away. The mud-brick and timber residence, made in stages with local materials, is rectangular, single-storey with a corrugated-iron roof. As a potter, Shanahan did not originally qualify as an official Cooperative member.This collection of almost 130 photos about places and people within the Shire of Nillumbik, an urban and rural municipality in Melbourne's north, contributes to an understanding of the history of the Shire. Published in 2008 immediately prior to the Black Saturday bushfires of February 7, 2009, it documents sites that were impacted, and in some cases destroyed by the fires. It includes photographs taken especially for the publication, creating a unique time capsule representing the Shire in the early 21st century. It remains the most recent comprehenesive publication devoted to the Shire's history connecting local residents to the past. nillumbik now and then (marshall-king) collection, art gallery, clifton pugh, dunmoochin, cottlesbridge, cottles bridge, barreenong road -

Ballarat Heritage Services

Ballarat Heritage ServicesPhotograph, Clare Gervasoni, Former Jubilee Methodist Church, Lake Wendouree, 2023, 09/11/2023

The Jubilee church on the edge of Lake Wendouree in Ballarat was opened in 1887, and held its jubilee in 1904. It is no longer operating as a church. This property was sold c1996. In its heighday it had a Sunday School and kindergarten. "A fire occurred at the Methodist Jubi lee Church Wendouree-parade, on Satur day evening. Flames were noticed at 7. p.m. issuing from the large kindergarten room attached to the chapel, and a Gregory-street resident telephoned the brigade. The firemen confined the blaze to the rear section and portion of the back wall of the church Itself. The damage is estimtacd at £100. (The Age 15 July 1935} Former weatherboard Church beside Lake Wendouree in Ballarat.jubilee church, jubilee methodist church, ballarat, wendouree, wendouree jubilee church -

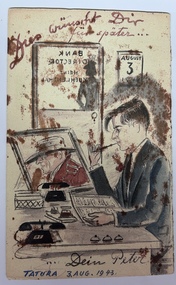

Tatura Irrigation & Wartime Camps Museum

Tatura Irrigation & Wartime Camps MuseumPhotograph - Photocopy of Painting, Bank Director, 3 August 1943

Heinz Kuehlenthal, Dunera refugee, internee in camp 3 during WW2. His name is on the door as the Bank Director.Photocopy of a painting depicting a man at his desk. He has short dark hair wearing a blue jacket and tie with white shirt. He has a pen in his right hand and holding it up to his lips. He has an open book in front of him. On the desk there are two black telephones, an ink well, letter tray and three bells. A large framed picture of a man in profile wearing a hat and burgandy jacket dominates the desk. A calendar on the wall shows August 3. The door to the office has a glass window with the wording "Bank director Heinz Kuelenthal" There is a shadow of a woman on the other side of the door. Hand written across the bottom of the picture is "....Dein Peter. Tatura 3 Aug 1943" Writing across the top is "Dries W...?? Dir fur spater...."heinz kuehlenthal, peter dein, dunera, camp 2, tatura -

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural Collection

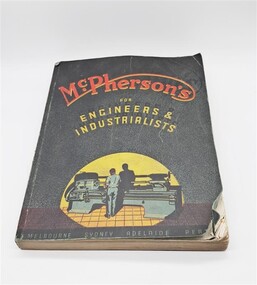

Glenelg Shire Council Cultural CollectionBook - Tool Catalogue, McPherson's Limited, McPherson's FOR ENGINEERS & INDUSTRIALISTS, 1949

This book is a catalogue issued for machinery merchants, tool specialists, suppliers of engineers' requisites, manufacturers of pumps, bolts, nuts, rivets, makers of high grade machine tools.Book is covered by green card and printed on the front with the title and a cartoon sketch/picture of a man standing facing away from viewer at a large industrial piece of machinery. Appears to be working. Picture includes an orange tiled floor and yellow wall. The book has 448 pages. Front cover: McPherson's FOR ENGINEERS & INDUSTRIALISTS MELBOURNE SYDNEY ADELAIDE PERTH Back Cover- McPherson's Ltd. 546-566 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE * Telephone: MY270 * Telegraphic Address: "MERCHANT" MELBOURNEnon-fictionThis book is a catalogue issued for machinery merchants, tool specialists, suppliers of engineers' requisites, manufacturers of pumps, bolts, nuts, rivets, makers of high grade machine tools. -

Whitehorse Historical Society Inc.

Whitehorse Historical Society Inc.Equipment - Magneto Telephone, C1930

Used to communicate with the local telephone exchange and for connection to other subscribers. The introduction of automatic exchanges saw the their demise. This phone was used in the family home of the donor at Caboolture (aboriginal for carpet snake) during the 1940s and 1950s.A magneto telephone for communication with a manual telephone exchange. The handle on the right hand side, which was turned to rotate the magneto to call the exchange - ask operator for a number and then to be connected. Telephone enclosed in a specially designed box for mounting on the wall. There was a bell on top which rang when the magneto ringer at the exchange was turned. Fitted with a carbon microphone mounted on the front of the box for the transmission of the spoken word and an electro- magnet. A receiver which hangs on the left hand side on a hook. The hook acts as the on and off switch to answer the call and to switch on the battery to provide power for the receiver and energize the transmitter. There is an angled ledge for writing any messages. There is no battery. The circuit for the phone is on the inside of the door to the interior of the phone. pHone is type CDA116 - PMG Registered - Ericsson.communication, telephonic