Showing 531 items

matching john britain

-

Moorabbin Air Museum

Moorabbin Air MuseumBook - BRITISH AIRCRAFT GUNS OF WORLD WAR TWO, ARMS AND ARMOUR PRESS, 1979

-

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone was an important commodity, used in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and toys.Whale bone vertebrae. Advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.Noneflagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked-coast, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Vertebrae, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Whalebone The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The bone of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as whalebone. Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale bone Vertebrae with advanced stage of calcification as indicated by deep pitting. Off white to grey.None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageAnimal specimen - Whale Jaw Bone, Undetermined

Prior to carrying out a detailed condition report of the cetacean skeletons, it is useful to have an understanding of the materials we are likely to encounter, in terms of structure and chemistry. This entry invites you to join in learning about the composition of whale bone and oil. Whale bone (Cetacean) bone is comprised of a composite structure of both an inorganic matrix of mainly hydroxylapatite (a calcium phosphate mineral), providing strength and rigidity, as well as an organic protein ‘scaffolding’ of mainly collagen, facilitating growth and repair (O’Connor 2008, CCI 2010). Collagen is also the structural protein component in cartilage between the whale vertebrae and attached to the fins of both the Killer Whale and the Dolphin. Relative proportions in the bone composition (affecting density), are linked with the feeding habits and mechanical stresses typically endured by bones of particular whale types. A Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758) skeleton (toothed) thus has a higher mineral value (~67%) than a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) (baleen) (~60%) (Turner Walker 2012). The internal structure of bone can be divided into compact and cancellous bone. In whales, load-bearing structures such as mandibles and upper limb bones (e.g. humerus, sternum) are largely composed of compact bone (Turner Walker 2012). This consists of lamella concentrically deposited around the longitudinal axis and is permeated by fluid carrying channels (O’Connor 2008). Cancellous (spongy) bone, with a highly porous angular network of trabeculae, is less stiff and thus found in whale ribs and vertebrae (Turner Walker 2012). Whale oil Whales not only carry a thick layer of fat (blubber) in the soft tissue of their body for heat insulation and as a food store while they are alive, but also hold large oil (lipid) reserves in their porous bones. Following maceration of the whale skeleton after death to remove the soft tissue, the bones retain a high lipid content (Higgs et. al 2010). Particularly bones with a spongy (porous) structure have a high capacity to hold oil-rich marrow. Comparative data of various whale species suggests the skull, particularly the cranium and mandible bones are particularly oil rich. Along the vertebral column, the lipid content is reduced, particularly in the thoracic vertebrae (~10-25%), yet greatly increases from the lumbar to the caudal vertebrae (~40-55%). The chest area (scapula, sternum and ribs) show a mid-range lipid content (~15-30%), with vertically orientated ribs being more heavily soaked lower down (Turner Walker 2012, Higgs et. al 2010). Whale oil is largely composed of triglycerides (molecules of fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule). In Arctic whales a higher proportion of unsaturated, versus saturated fatty acids make up the lipid. Unsaturated fatty acids (with double or triple carbon bonds causing chain kinks, preventing close packing (solidifying) of molecules), are more likely to be liquid (oil), versus solid (fat) at room temperature (Smith and March 2007). Objects Made From the Whaling Industry We all know that men set forth in sailing ships and risked their lives to harpoon whales on the open seas throughout the 1800s. And while Moby Dick and other tales have made whaling stories immortal, people today generally don't appreciate that the whalers were part of a well-organized industry. The ships that set out from ports in New England roamed as far as the Pacific in hunt of specific species of whales. Adventure may have been the draw for some whalers, but for the captains who owned whaling ships, and the investors which financed voyages, there was a considerable monetary payoff. The gigantic carcasses of whales were chopped and boiled down and turned into products such as the fine oil needed to lubricate increasing advanced machine tools. And beyond the oil derived from whales, even their bones, in an era before the invention of plastic, was used to make a wide variety of consumer goods. In short, whales were a valuable natural resource the same as wood, minerals, or petroleum we now pump from the ground. Oil From Whale’s Blubber Oil was the main product sought from whales, and it was used to lubricate machinery and to provide illumination by burning it in lamps. When a whale was killed, it was towed to the ship and its blubber, the thick insulating fat under its skin, would be peeled and cut from its carcass in a process known as “flensing.” The blubber was minced into chunks and boiled in large vats on board the whaling ship, producing oil. The oil taken from whale blubber was packaged in casks and transported back to the whaling ship’s home port (such as New Bedford, Massachusetts, the busiest American whaling port in the mid-1800s). From the ports it would be sold and transported across the country and would find its way into a huge variety of products. Whale oil, in addition to be used for lubrication and illumination, was also used to manufacture soaps, paint, and varnish. Whale oil was also utilized in some processes used to manufacture textiles and rope. Spermaceti, a Highly Regarded Oil A peculiar oil found in the head of the sperm whale, spermaceti, was highly prized. The oil was waxy, and was commonly used in making candles. In fact, candles made of spermaceti were considered the best in the world, producing a bright clear flame without an excess of smoke. Spermaceti was also used, distilled in liquid form, as an oil to fuel lamps. The main American whaling port, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was thus known as "The City That Lit the World." When John Adams was the ambassador to Great Britain before serving as president he recorded in his diary a conversation about spermaceti he had with the British Prime Minister William Pitt. Adams, keen to promote the New England whaling industry, was trying to convince the British to import spermaceti sold by American whalers, which the British could use to fuel street lamps. The British were not interested. In his diary, Adams wrote that he told Pitt, “the fat of the spermaceti whale gives the clearest and most beautiful flame of any substance that is known in nature, and we are surprised you prefer darkness, and consequent robberies, burglaries, and murders in your streets to receiving as a remittance our spermaceti oil.” Despite the failed sales pitch John Adams made in the late 1700s, the American whaling industry boomed in the early to mid-1800s. And spermaceti was a major component of that success. Spermaceti could be refined into a lubricant that was ideal for precision machinery. The machine tools that made the growth of industry possible in the United States were lubricated, and essentially made possible, by oil derived from spermaceti. Baleen, or "Whalebone" The bones and teeth of various species of whales were used in a number of products, many of them common implements in a 19th century household. Whales are said to have produced “the plastic of the 1800s.” The "bone" of the whale which was most commonly used wasn’t technically a bone, it was baleen, a hard material arrayed in large plates, like gigantic combs, in the mouths of some species of whales. The purpose of the baleen is to act as a sieve, catching tiny organisms in sea water, which the whale consumes as food. As baleen was tough yet flexible, it could be used in a number of practical applications. And it became commonly known as "whalebone." Perhaps the most common use of whalebone was in the manufacture of corsets, which fashionable ladies in the 1800s wore to compress their waistlines. One typical corset advertisement from the 1800s proudly proclaims, “Real Whalebone Only Used.” Whalebone was also used for collar stays, buggy whips, and toys. Its remarkable flexibility even caused it to be used as the springs in early typewriters. The comparison to plastic is apt. Think of common items which today might be made of plastic, and it's likely that similar items in the 1800s would have been made of whalebone. Baleen whales do not have teeth. But the teeth of other whales, such as the sperm whale, would be used as ivory in such products as chess pieces, piano keys, or the handles of walking sticks. Pieces of scrimshaw, or carved whale's teeth, would probably be the best remembered use of whale's teeth. However, the carved teeth were created to pass the time on whaling voyages and were never a mass production item. Their relative rarity, of course, is why genuine pieces of 19th century scrimshaw are considered to be valuable collectibles today. Reference: McNamara, Robert. "Objects Made From the Whaling Industry." ThoughtCo, Jul. 31, 2021, thoughtco.com/products-produced-from-whales-1774070.Whale bone during the 17th, 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries was an important industry providing an important commodity. Whales from these times provided everything from lighting & machine oils to using the animal's bones for use in corsets, collar stays, buggy whips, and many other everyday items then in use.Whale jaw bone one side, long & curved with advanced stage of calcification off white to grey.None.warrnambool, flagstaff-hill, flagstaff-hill-maritime-museum, maritime-museum, shipwreck-coast, flagstaff-hill-maritime-village, whale bones, whale skeleton, whales, whale bone, corsets, toys, whips, whaleling industry, maritime fishing, whalebone -

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.Sign - Pub Sign, 1920

The sons of a spirits dealer, Andrew and John Usher created one of the world’s most successful blended Scotch whiskies, Old Vatted Glenlivet, and played a key role in building the North British distillery. But they were also responsible for one of the most misunderstood lawsuits in Scotch history – the trademark battle for ‘Glenlivet’. Iain Russell reports. Three badly damaged paper labels on the back. A mirror is mounted on a one centimetre thick, 67 by 43 centimetres wooden frame with 18 centimetres by three centimetres decorative extensions on all sides. there two pieces of metal on the top to hang the mirror. A box nine six by four centimetres is mounted on each side, one is labeled MATCHES and the other CIGAR CUTTER both have ANDREW USHER & Co written on them. Behind the glass is gold coloured writing with black shadows stating USHER'S "SPECIAL RESERVE" & "O.V.C." WHISKIESpub mirror, andrew usher, o.v.c. whiskies -

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.Photograph - BRITISH QUEEN HOTEL: BENDIGO, late 1800's

The "British Queen Hotel", in Bridge street, Bendigo was first licensed to Squire Barlow (1817-1882), a Lancashire man who came to Australia in 1853 with his two eldest sons, travelling on the "Goldfinder". His wife Mary (nee Taylor, 1814-1891) soon followed with the rest of their children. One more child was born in Sandhurst in 1856. Squire and Mary had married in 1838, "The British Queen" was taken over by John Crowe (1825-1882) some time after 1876. John had previously been the licesee of the Globe Hotel, also in Bridge Street. When John died in 1881, his son Robert Phillip Crowe (Phillip) transferred the licence to John Hope in 1882.Black and white photograph. Buiilding Crowe's British Queen Hotel, 4 people, 2 boys at left, man with hat at centre, lady with long dress centre right. Large hotel light above door, laneway beside building at left with creeper above. On windows of building ' Crowe's British Queen Hotel' On parapet, partially visible ' British Queen..'cottage, miners -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillageFurniture - Desk, Foy & Gibson, Circa 1880s

The design of this small disc is from the Australian Colonial period. The cedar wood desk was made in Australian by Foy & Gibson in the 1880s, most probably in the business’s works in Collingwood, Victoria. The heavy brass locks fitted into the desk drawers were made by the famous Hobbs & Co of London, mid-late 19th century. In 1860 the business changed hands but the locks were still branded Hobbs & Co. The desk is branded with the symbol of Victoria’s Public Works Department. There is currently no information on when, where and by whom this desk was used. However, a very similar desk with Hobbs & Co. locks is on site at the Point Hicks Lightstation in Victoria and was formerly used by the Point Hicks head light keeper there. Other light stations also have similar desks from the P.W.D. (see also ‘Desk, Parks Victoria – Point Hicks Lightstation, Victorian Collections’.) HOBBS & CO., LONDON Alfred Charles Hobbs, 1812-1891, was American born. He became an executive salesman in 1840 for renowned lock manufacturer Day & Newell. His technique of exposing the weaknesses of people’s current locks was very successful in generating sales. He represented Day & Newell at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, competing with other lock makers. Through the Exhibition he became famous for picking the best trusted Bramah and Chubb locks. Hobbs’ fame led him to found his own company in 1851 then register it in 1852 as Hobbs & Co., London. Hobbs was awarded the Telford Medal by the British Institution of Civil Engineers in 1854 for his paper 'On the Principles and Construction of Locks'. In 1855 the very successful company added partners and became Hobbs, Ashley and Co. In 1860, it traded under the name of Hobbs, Hart & Co. and was based in Cheapside London, where the business remained. Hobbs then returned to America, having sold the complete company to John Mathias Hart. He briefly returned to attend the 21st anniversary celebrations of the successful business in 1872. Hobbs kept himself busy in America, inventing and manufacturing firearm ammunition, for which he held several patents. He passed away there in 1891, a month after his 70th birthday. FOY & GIBSON Mark Foy wan an Irish draper who migrated to Bendigo, Victoria in 1858, attracted by the gold rush. He lived and worked in the area, establishing a drapery business. In the 1870s he moved to Melbourne where there were better prospects for expansion. He chose a place in Smith Street, Collingwood, a suburb of Melbourne, and started his business at the rear. In 1883 Foy retired, bringing in William Gibson as a partner, and then transferred his own share of the company to his son Francis Foy. Not long afterwards Francis sold his half share to Gibson, and the business continued under the name of Foy & Gibson. Francis Foy and he and his brother Mark Foy (junior) moved to Sydney. They established a business there in 1885, named after their father, Mark Foy. Gibson added to his business by starting his own manufacturing works from 1887, producing clothing, millinery, furniture, bedding and hardware for his stores. The factories, warehouses and stores complex became one of Victoria’s largest employers. He set up branches of his stores in Perth, Brisbane and Adelaide and two more branches in Melbourne. Foy & Gibson (usually referred to as Foys) became one of Australia’s largest retail department stores. In 1931 Foy’s little house in Collingwood was still part of the entrance to Foy & Gibson Emporium. In 1955 the company was bought out by Cox Brothers. Later on the stores were sold to various businesses such as David Jones, Woolworths and Harris Scarfe. In 1968 Cox Brothers went into receivership, ending almost 100 years of the business known as Foy’s. The former Foy & Gibson Complex is registered by Heritage Council Victoria. “Designed by William Pitt, this magnificent 19th and early 20th century complex of factories, warehouses and showrooms saw the production of a remarkable range of goods for Foy & Gibson, Melbourne’s earliest department store chain”. (Quoted from the Plaque erected by the Collingwood Historical Society 2007) P.W.D. – Public Works Department, Victoria The desk is stamped “P.W.D,” signifying that it is from the Public Works Department in Victoria, which operated from 1855-1987. The department was responsible for, among other things, the design and supply of office furniture and equipment for public buildings and organisations. This desk is significant historically as it originated from Foy & Gibson, a colonial Australian company that had a positive and strong impact on employment, manufacturing and retailing in Melbourne, Victoria and Australia. The significance of Foy & Gibson to Victoria’s and Australia’s history is marked by the Collingwood Complex being registered in both Heritage Victoria Register (H0755, H0897 and H0896) and National Trust Register (B2668). This locks on this desk are significant for their connection with their manufacturer, Hobbs & Co, who invented a lock that surpassed the security of any other locks produced in the mid-19th century. Desk; Australian Colonial cedar desk, honey coloured. Desktop has a wooden border with a rolled edge and a fitted timber centrepiece. The four tapered legs are tulip turned. Two half-width drawers fit side by side and extend the full depth of the desk. The drawers have dovetail joints. Each drawer has two round wooden knob handles, a keyhole and a fitted, heavy brass lever lock. Inscriptions are on the desktop, drawers, desk leg and lock. Made in Australia circa 1880 by Foy & Gibson, lock made by Hobbs & Co, London.Impressed into timber frame of one drawer “FOY & GIBSON” Impressed into lock “HOBBS & CO / LONDON”, “MACHINE MADE”, “LEVER” Impressed along the front edge of the desktop [indecipherable] text. Impressed into the timber of right front leg “P. W. D.” below a ‘crown’ symbol Handwritten in white chalk under a drawer “206” flagstaff hill, warrnambool, shipwrecked coast, flagstaff hill maritime museum, maritime museum, shipwreck coast, flagstaff hill maritime village, great ocean road, desk, cedar desk, colonial desk, 1880s desk, australian colonial furniture, furniture, office furniture, office equipment, australian made furniture, colonial furniture, colonial hardware, foy & gibson, alfred charles hobbs, hobbs & co london, hobs & co lever lock, cabinetry lock, machine made lever lock, p.w.d., public works department victoria, day & newell, great exhibition of 1851, bramah lock, chubb lock, telford medal 1854, cheapside london, mark foy, mark foy – bendigo draper, smith street collingwood, william gibson, foy & gibson emporium, foy & gibson complex, cox brothers -

Kew Historical Society Inc

Kew Historical Society IncWork on paper - Sepia Wash & Ink, G B Richardson, Creek and Old Watering Stage, on the Yarra, East Collingwood, 1854, 1854

Blind Creek was located between the Abbotsford Convent and what is now the Collins Bridge in Studley Park. In an 1858 map of East Collingwood by Clement Hodgkinson, in the State Library of Victoria, one can see how the creek was originally a significant landmark in Collingwood; remaining vacant land until a barrel drain enclosed it. The area was later filled in, surveyed and developed. The position where Blind Creek entered the Yarra was in the immediate vicinity of Hodgson’s Punt, which had linked Kew to the other side of the Yarra from 1839. The Punt was purchased by the Colonial Government in 1852 and was in use until the opening of the Studley Park Road (Johnston Street) Bridge in 1858 made its continued use redundantThe point of view selected by the artist for the watercolour is from the banks of Blind Creek in East Collingwood, looking across the Yarra to the Kew side of the river.Inscribed verso 'Creek and Old Watering stage, on the Yarra East Collingwood 1854 / Trees, stage, &c have long since disappeared / [Artist Signature] / FT 110 / Creek itself now being filled in 1903.gb richardson, blind creek - abbotsford, yarra river - abbotsford (vic) - kew (vic), colonial artists, australian art - 19th century, george bouchier richardson -

Port Melbourne Historical & Preservation Society

Port Melbourne Historical & Preservation SocietyPostcard - Various Port Melbourne views, 2015 - 2016

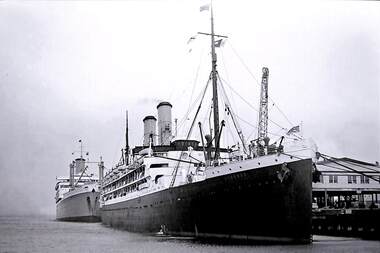

A set (11) of postcards from historic photographs produced by John Hoskin, trading as Great Southern Card Publishing, Australia. .01 - J Kitchen & Sons factory in 1939 .02 - J Kitchen & Sons factory 1939 also showing Port Melbourne Football Ground .03 - Strathaird - 1934 - departing Station Pier .04 - British Aircraft Carriers at Station Pier from 23 to 31 January 1946 .05 - USA warships at Princes Pier 26July to 6 August 1925 .06 - Railway Pier c 1890 .07 -Wanganella - 1946 at Station Pier .08 - Uraba minesweeper at Station Pier 1946 .09 - Oronsay and Ormonde at Station Pier c 1951/52 .10 - Empress of Britain and Reliance at Station Pier 6 April 1938 transport - shipping, piers and wharves, industry, manufacturing, piers and wharves - station pier, piers and wharves - princes pier, piers and wharves - railway pier, j kitchen & sons pty ltd, wanganella, strathaird, oronsay, ormonde, uralba, hms implacable, hms glory, hms indefatigable -

Melbourne Tram Museum

Melbourne Tram MuseumDocument - Report, Victorian Railways, "Annual Report 1948-49 - Victorian Railways", 1949

Report - foolscap size, 100 pages, bound with staples along left hand edge and glued into a printed colour cover titled "Annual Report 1948-49 - Victorian Railways". Details the results of the Victorian Railways operations for each station, division, traffic and written information including an investigation by Mr John Elliot of the Southern Region of British Railways into the organisation of Transport in Victoria. Has the results for the two tramways operated by the VR of Appendix 7 (page 55) and the last page of the report.On cover stamped "Australian Electric Traction Association" and hand written Library numbers and notes.trams, tramways, victorian railways, vr, st kilda brighton, tramways, railways -

Marysville & District Historical Society

Marysville & District Historical SocietyPostcard (item) - Colour tinted postcard, Valentine Publishing Co. Pty. Ltd, "ROSELEIGH," MARYSVILLE. V.7, 1923-1963

A colour tinted postcard of Roseleigh Guest House in Marysville that was produced by Valentine Publishing Co. Pty Ltd as a souvenir of Marysville.A colour tinted postcard of Roseleigh Guest House in Marysville that was produced by Valentine Publishing Co. Pty Ltd as a souvenir of Marysville.VALENTINE'S/ POST CARD/ SENDING YOU GREETINGS/ FOR ADDRESS ONLY PRINTED IN GT. BRITAIN THIS IS A REAL PHOTOGRAPH Published by The Valentine Publishing Co., Sydney and Melbourne. 3016marysville, victoria, australia, roseleigh guest house, grieve family, thomas charles grieve, john arthur grieve, rose grieve, ackerman family, mary moyne, elise ackerman, ken mcleod, george peters, rose emily pullum, beltana, rose lillian smith, ivy may grieve, alexander james ficinus, raymond charles smith, postcard, souvenir, valentine's publishing co. pty ltd -

Marysville & District Historical Society

Marysville & District Historical SocietyPostcard (item) - Colour tinted postcard, Valentine Publishing Co. Pty. Ltd, "ROSELEIGH," MARYSVILLE. V.7, 1923-1963

A colour tinted postcard of Roseleigh Guest House in Marysville that was produced by Valentine Publishing Co. Pty Ltd as a souvenir of Marysville.A colour tinted postcard of Roseleigh Guest House in Marysville that was produced by Valentine Publishing Co. Pty Ltd as a souvenir of Marysville.VALENTINE'S/ POST CARD/ SENDING YOU GREETINGS/ FOR ADDRESS ONLY PRINTED IN GT. BRITAIN THIS IS A REAL PHOTOGRAPH Published by The Valentine Publishing Co., Sydney and Melbourne. marysville, victoria, australia, roseleigh guest house, grieve family, thomas charles grieve, john arthur grieve, rose grieve, ackerman family, mary moyne, elise ackerman, ken mcleod, george peters, rose emily pullum, beltana, rose lillian smith, ivy may grieve, alexander james ficinus, raymond charles smith, postcard, souvenir, valentine's publishing co. pty ltd -

Victorian Railway History Library

Victorian Railway History LibraryBook, Flint, Edward John, Tracks to Dieselization BR v QR 1948 - 1969, 2012

Comparing the dieselization of the British Railways to that of Queensland Government railways between 1948 & 1969.index, ill, maps, p.245.non-fictionComparing the dieselization of the British Railways to that of Queensland Government railways between 1948 & 1969.vicrail - victoria - history, locomotives - victoria - history -

Mont De Lancey

Mont De LanceyBook, Oxford University Press, The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testaments, 1840

The Holy Bible containing the Old and New testaments: translated out of the original tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, By His Majesty's Special Command. Appointed to be read in churches.A faded black hardcover Holy Bible with embossed pattern on the front and back covers. The front has stamped inside a circle the words, For Foreign and British Bible Society. The endpaper at the front is coming away from the spine, there are stains, foxing, ink markings and tears inside. Text is clear. The spine has faded patterning all along it with Holy Bible printed in gold lettering at the top. There is an inscription from Psalms 1 at the front from Henry Sebire who owned the Bible in June 15 /57. At the back is a handwritten Sebire Family Tree. Overall for it's age it is in remarkably reasonable condition. non-fictionThe Holy Bible containing the Old and New testaments: translated out of the original tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, By His Majesty's Special Command. Appointed to be read in churches. holy bible, religion -

Wangaratta RSL Sub Branch

Wangaratta RSL Sub BranchLetter - Personal papers, Lieut. A.J Cruise MBE

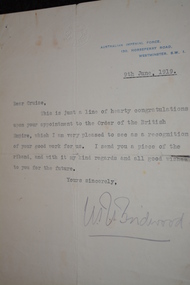

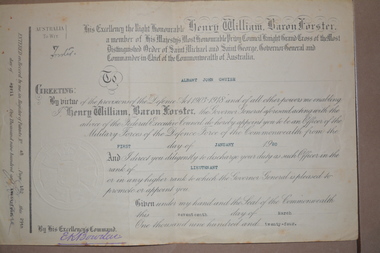

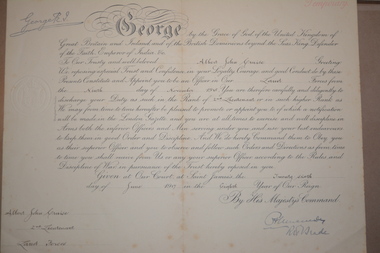

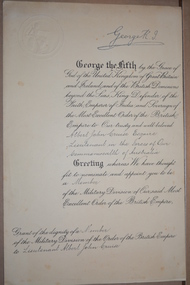

Personal documents and letters belonging to Lieutenant Albert John CRUISE born 13/4/1883 at Nathalia in Victoria. Educated at Geelong College. Enlisted in NSW on 29/8/1914 as Private No 86 1st Battalion. Promoted to L/cpl on 25/7/1915 then Lieutenant on 9/11/1915. He was nominated and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire - Military Division for conspicuous services rendered as follows:- 'During the period 16-19 September to 11th November 1918 this officer has shown conspicuous devotion to duty and great gallantry in the performance of that duty. He has organised salvage parties and was instrumental during the advance in September in making German Dumps of HE material available for use in forward positions thus saving time and transport. His work throughout has been characterised by marked individuality and courage in the forward area and has been productive of far reaching results. He served at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Due to pneumonia and enteric he returned to Australia in early 1916 to recuperate and married before returning in August 1916. In September 1919 he returned to Australia on board HMAT Takadaussie (refer item 363) and discharged on 7/11/1919. He later served full time with the CMF from 15/5/1940 - 17/10/1943. He died in 1952Parchment of Appointed to rank 2nd Lieutenant on 9/11/1915 by King George V - Document dated 26/6/1917 Parchment of Appointment as a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire by King George V dated 3/6/1919 Two parchments issued by the Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia Appointed Lieutenant of the Military Forces of the Defence Force of the Commonwealth from 1/1/1920 by Henry William, Baron Forster Appointed Lieutenant of the Reserve Military Forces of the Commonwealth from 13/4/1940 by Alexander Gore Arkwright, Baron GowrieFour large parchment documents Two Australian Military Forces certificates and one form Five original letters One copy of letter written in French Seven copies of typed letters AIF Military PassCream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script and stamped George R I dated 26/6/1917 and 3/6/1919 Cream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script issued by the Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia dated 17/3/1924 and 21/4/1941 AMF Recommendation for Promotion V 84119 Lieut Cruise - form incomplete AMF Certificate of Release from War Service No 11943 - V84199 Lieut Cruise AMF Certificate of Service of an Officer No 33461 -V84119 Lieut Cruise Typed letter dated 13/10/1919 from Commonwealth of Australia Dept of Defence to Lieut Cruise referring to London Gazette extract - Member of the British Empire - Military Division Typed letter embossed with seal dated 9/6/1919 signed W Birdwood Handwritten in blue ink with "Denman Chambers" imprint top right corner letter of reference signed B V Stacy formerly Lieut. Col., Commanding 1st Bn AIF Typed letter with AIF letterhead dated 1/6/1927 Typed letter with The Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs letterhead dated 24/1/1950 Typed copy of letter of gratitude in French dated 18/6/1918 from Military Attache General Pierre de Laguiche - stamped with Statue of Liberty AIF Military Pass dated 25/6/1919 issued to Lieut Cruiselt. a j cruise mbe, ww1 -

Wangaratta RSL Sub Branch

Wangaratta RSL Sub BranchDocument - Personal papers, Lieut. A.J Cruise MBE

Personal documents and letters belonging to Lieutenant Albert John CRUISE born 13/4/1883 at Nathalia in Victoria. Educated at Geelong College. Enlisted in NSW on 29/8/1914 as Private No 86 1st Battalion. Promoted to L/cpl on 25/7/1915 then Lieutenant on 9/11/1915. He was nominated and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire - Military Division for conspicuous services rendered as follows:- 'During the period 16-19 September to 11th November 1918 this officer has shown conspicuous devotion to duty and great gallantry in the performance of that duty. He has organised salvage parties and was instrumental during the advance in September in making German Dumps of HE material available for use in forward positions thus saving time and transport. His work throughout has been characterised by marked individuality and courage in the forward area and has been productive of far reaching results. He served at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Due to pneumonia and enteric he returned to Australia in early 1916 to recuperate and married before returning in August 1916. In September 1919 he returned to Australia on board HMAT Takadaussie (refer item 363) and discharged on 7/11/1919. He later served full time with the CMF from 15/5/1940 - 17/10/1943. He died in 1952Parchment of Appointed to rank 2nd Lieutenant on 9/11/1915 by King George V - Document dated 26/6/1917 Parchment of Appointment as a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire by King George V dated 3/6/1919 Two parchments issued by the Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia Appointed Lieutenant of the Military Forces of the Defence Force of the Commonwealth from 1/1/1920 by Henry William, Baron Forster Appointed Lieutenant of the Reserve Military Forces of the Commonwealth from 13/4/1940 by Alexander Gore Arkwright, Baron GowrieFour large parchment documents Two Australian Military Forces certificates and one form Five original letters One copy of letter written in French Seven copies of typed letters AIF Military PassCream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script and stamped George R I dated 26/6/1917 and 3/6/1919 Cream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script issued by the Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia dated 17/3/1924 and 21/4/1941 AMF Recommendation for Promotion V 84119 Lieut Cruise - form incomplete AMF Certificate of Release from War Service No 11943 - V84199 Lieut Cruise AMF Certificate of Service of an Officer No 33461 -V84119 Lieut Cruise Typed letter dated 13/10/1919 from Commonwealth of Australia Dept of Defence to Lieut Cruise referring to London Gazette extract - Member of the British Empire - Military Division Typed letter embossed with seal dated 9/6/1919 signed W Birdwood Handwritten in blue ink with "Denman Chambers" imprint top right corner letter of reference signed B V Stacy formerly Lieut. Col., Commanding 1st Bn AIF Typed letter with AIF letterhead dated 1/6/1927 Typed letter with The Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs letterhead dated 24/1/1950 Typed copy of letter of gratitude in French dated 18/6/1918 from Military Attache General Pierre de Laguiche - stamped with Statue of Liberty AIF Military Pass dated 25/6/1919 issued to Lieut Cruiselt. a j cruise mbe, ww1 -

Bendigo Military Museum

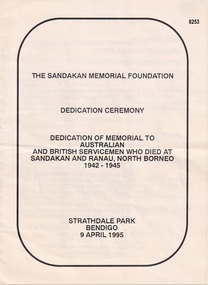

Bendigo Military MuseumPamphlet - SANDAKAN MEMORIAL 1995, C. 1995

This service was to dedicate a Memorial to Australian & British Servicemen who died at Sandakan and Ranau, North Borneo 1942 - 1945. It was unveiled at Strathdale Park Bendigo on 9.4.1995. The Official Party were; Mr Peter Ross Edwards AM, Chief Commissioner The City of Greater Bendigo, Mr J.S. Millner AM, Chairman The Sandakan Memorial Foundation. The Requiem was read by Father John Brendan Rogers OFM. Unveiling the Memorial by, Mr Peter Ross Edwards AM. Dedication of the Memorial by; Father John Brendan Rogers OFM, Chaplain 8th Division Sandakan and Kuching, Chaplain Gary Kenney, Australian Army. Laying of the wreaths, Wreath Marshalls supplied by Bendigo RSL Sub Branch, Australian Army Band Melbourne. The ODE was read by; President Bendigo RSL Mr Cliff Clohesy. The Catalflaque Party was supplied by; Army School of Survey Regiment Bendigo.Pamphlet off white colour, A4 folded making 8 pages total, all print in black, one staple central holding together.On the front, "The Sandakan Memorial Foundation, Strathdale Park Bendigo 9 April 1995"brsl, smirsl, sandakan, strathdale -

Wangaratta RSL Sub Branch

Wangaratta RSL Sub BranchDocument - Personal papers, Lieut. A.J Cruise MBE

Personal documents and letters belonging to Lieutenant Albert John CRUISE born 13/4/1883 at Nathalia in Victoria. Educated at Geelong College. Enlisted in NSW on 29/8/1914 as Private No 86 1st Battalion. Promoted to L/cpl on 25/7/1915 then Lieutenant on 9/11/1915. He was nominated and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire - Military Division for conspicuous services rendered as follows:- 'During the period 16-19 September to 11th November 1918 this officer has shown conspicuous devotion to duty and great gallantry in the performance of that duty. He has organised salvage parties and was instrumental during the advance in September in making German Dumps of HE material available for use in forward positions thus saving time and transport. His work throughout has been characterised by marked individuality and courage in the forward area and has been productive of far reaching results. He served at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Due to pneumonia and enteric he returned to Australia in early 1916 to recuperate and married before returning in August 1916. In September 1919 he returned to Australia on board HMAT Takadaussie (refer item 363) and discharged on 7/11/1919. He later served full time with the CMF from 15/5/1940 - 17/10/1943. He died in 1952Parchment of Appointed to rank 2nd Lieutenant on 9/11/1915 by King George V - Document dated 26/6/1917Four large parchment documents Two Australian Military Forces certificates and one form Five original letters One copy of letter written in French Seven copies of typed letters AIF Military PassCream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script and stamped George R I dated 26/6/1917 and 3/6/1919 Cream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script issued by the Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia dated 17/3/1924 and 21/4/1941 AMF Recommendation for Promotion V 84119 Lieut Cruise - form incomplete AMF Certificate of Release from War Service No 11943 - V84199 Lieut Cruise AMF Certificate of Service of an Officer No 33461 -V84119 Lieut Cruise Typed letter dated 13/10/1919 from Commonwealth of Australia Dept of Defence to Lieut Cruise referring to London Gazette extract - Member of the British Empire - Military Division Typed letter embossed with seal dated 9/6/1919 signed W Birdwood Handwritten in blue ink with "Denman Chambers" imprint top right corner letter of reference signed B V Stacy formerly Lieut. Col., Commanding 1st Bn AIF Typed letter with AIF letterhead dated 1/6/1927 Typed letter with The Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs letterhead dated 24/1/1950 Typed copy of letter of gratitude in French dated 18/6/1918 from Military Attache General Pierre de Laguiche - stamped with Statue of Liberty AIF Military Pass dated 25/6/1919 issued to Lieut Cruiselt. a j cruise mbe, ww1 -

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.

Bendigo Historical Society Inc.Document - VICTORIA HILL - THE RICH VICTORIA HILL AND IT'S HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

Two copies of document : nineteen handwritten pages of notes on 'The Rich Victoria Hill and Its Historical Association' Signed by A Richardson and dated 30 - 8 - 1971. and a typed copy of same. Notes include: Introduction, Hotels, Mines, Mining History and descriptions of features where the signposts are. Mines mentioned in the text are: North Old Chum. Ballerstedt's first open cut, Lansell's Big 180. 20 head stamper, Lansell's Cleopatra Needle, Victoria Quartz Mine. Cleopatra's Needle was a square sectioned brick chimney with this four sided pyramidal chimney top with four vents to allow the smoke to escape whatever the direction of the wind. It was demolished in the 1950's as it had a bend in it and it was considered unsafe. Lansell had two other mines with similar chimneys, the '222' in Chum Street and his 'Sandhurst' or 'Needle' mine near the Bendigo, Eaglehawk boundary. Notes prepared by Albert Richardson.mine, gold, victoria hill, victoria hill, the rich victoria hill and it's historical association, j. n. macartney, quartz miner's arms hotel, ironbark methodist church, greek orthodox church, john brown knitwear factory, little 180 mine, geo lansell, conrad heinz, british & american hotel, victoria reef gold mining coy, manchester arms hotel, housing commission homes, ironbark (victoria reef gold mines, hercules and energetic, midway, wittscheibe, gt central victoria, wm rae, mr & mrs conroy, wm rae jr, central nell gwynne, moorhead's shop, gill family, gold mines hotel, david chaplin sterry, pioneer, new chum and victoria, burrowes and sterry, new chum and victoria tribute, rotary club of bendigo south, big 180, victoria quartz mines, jeweller's shop, bendigo and district tourist association, north old chum mine, john wybrandt, ballerstedt's first open-cut, j c t christopher ballerstedt, ballerstedt's mine, bendigo cemetry, lansell's 'cleopatra nedle' type chimney, 222 mine, sandhurst or 'needle' mine, victoria quartz mine, victoria reef quartz company, mr e j dunn, eureka ext'd, new chum railway, pearl, bendigo advertiser 16 june 1910, victoria consols, shamrock, shenandoah, victoria quartz dams, rae's open cut, prospecting tunnels, floyd's small 5 head crushing battery, gt central victoria (midway) shaft, midway no 2, midway north, ballerstedt's small 24 yard claim, the humboldt, the tribute coy, advance, luffsman and sterry's claim, a round shaft, chinese joss house, lansell's fortuna, p m g repeater station, a richardson -

Wangaratta RSL Sub Branch

Wangaratta RSL Sub BranchEquipment - Canvas Dispatch Bag

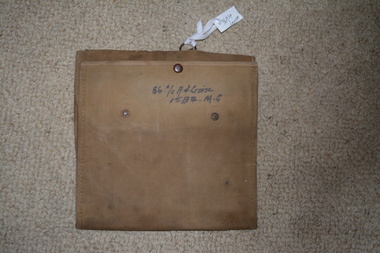

Item belonging to Lieutenant Albert John CRUISE born 13/4/1883 at Nathalia in Victoria. Educated at Geelong College. Enlisted in NSW on 29/8/1914 as Private No 86 1st Battalion. Promoted to L/cpl on 25/7/1915 then Lieutenant on 9/11/1915. He was nominated and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire - Military Division for conspicuous services rendered as follows:- 'During the period 16-19 September to 11th November 1918 this officer has shown conspicuous devotion to duty and great gallantry in the performance of that duty. He has organised salvage parties and was instrumental during the advance in September in making German Dumps of HE material available for use in forward positions thus saving time and transport. His work throughout has been characterised by marked individuality and courage in the forward area and has been productive of far reaching results. He served at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Due to pneumonia and enteric he returned to Australia in early 1916 to recuperate and married before returning in August 1916. In September 1919 he returned to Australia on board HMAT Takadaussie (refer item 363) and discharged on 7/11/1919. He later served full time with the CMF from 15/5/1940 - 17/10/1943. He died in 1952 Insufficient detail to positively identify Lieutenant Peters - possibly Captain Gordon Peters DSO born 5/7/1894 Adelaide South Australia. The 12th Infantry were recruited from Tasmania, South Australian and Western Australia. 9 Jun 1915: Enlisted AIF WW1, Lieutenant, 12th Infantry Battalion 21 Sep 1915: Involvement Lieutenant, 12th Infantry Battalion 21 Sep 1915: Embarked Lieutenant, 12th Infantry Battalion, HMAT Star of England, Adelaide 16 May 1917: Promoted AIF WW1, Captain, 12th Infantry Battalion 27 Jul 1919: Discharged AIF WW1, Captain, 12th Infantry Battalion 15 Sep 1919: Honoured Commander of the Order of the British Empire 30 Oct 1919: Honoured Mention in Dispatches, unknownBrown canvas double sided pouch bag that opens out to reveal two clear plastic sleeves one of which has a brown cloth overlay. Attached on top is small metal ring near tear repaired by hand stitching.Handwritten under rear flap 86 L/C A J Cruise 1st Bn M.G. Handwritten inside front pouch Lt. Peters 12th Inflt. a j cruise mbe, ww1 -

Wangaratta RSL Sub Branch

Wangaratta RSL Sub BranchDocument - Personal papers, Lieut. A.J Cruise MBE

Personal documents and letters belonging to Lieutenant Albert John CRUISE born 13/4/1883 at Nathalia in Victoria. Educated at Geelong College. Enlisted in NSW on 29/8/1914 as Private No 86 1st Battalion. Promoted to L/cpl on 25/7/1915 then Lieutenant on 9/11/1915. He was nominated and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire - Military Division for conspicuous services rendered as follows:- 'During the period 16-19 September to 11th November 1918 this officer has shown conspicuous devotion to duty and great gallantry in the performance of that duty. He has organised salvage parties and was instrumental during the advance in September in making German Dumps of HE material available for use in forward positions thus saving time and transport. His work throughout has been characterised by marked individuality and courage in the forward area and has been productive of far reaching results. He served at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Due to pneumonia and enteric he returned to Australia in early 1916 to recuperate and married before returning in August 1916. In September 1919 he returned to Australia on board HMAT Takadaussie (refer item 363) and discharged on 7/11/1919. He later served full time with the CMF from 15/5/1940 - 17/10/1943. He died in 1952Parchment of Appointed to rank 2nd Lieutenant on 9/11/1915 by King George V - Document dated 26/6/1917 Parchment of Appointment as a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire by King George V dated 3/6/1919Four large parchment documents Two Australian Military Forces certificates and one form Five original letters One copy of letter written in French Seven copies of typed letters AIF Military PassCream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script and stamped George R I dated 26/6/1917 and 3/6/1919 Cream Parchment with embossed seal, italic script issued by the Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia dated 17/3/1924 and 21/4/1941 AMF Recommendation for Promotion V 84119 Lieut Cruise - form incomplete AMF Certificate of Release from War Service No 11943 - V84199 Lieut Cruise AMF Certificate of Service of an Officer No 33461 -V84119 Lieut Cruise Typed letter dated 13/10/1919 from Commonwealth of Australia Dept of Defence to Lieut Cruise referring to London Gazette extract - Member of the British Empire - Military Division Typed letter embossed with seal dated 9/6/1919 signed W Birdwood Handwritten in blue ink with "Denman Chambers" imprint top right corner letter of reference signed B V Stacy formerly Lieut. Col., Commanding 1st Bn AIF Typed letter with AIF letterhead dated 1/6/1927 Typed letter with The Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs letterhead dated 24/1/1950 Typed copy of letter of gratitude in French dated 18/6/1918 from Military Attache General Pierre de Laguiche - stamped with Statue of Liberty AIF Military Pass dated 25/6/1919 issued to Lieut Cruiselt. a j cruise mbe, ww1 -

Bendigo Military Museum

Bendigo Military MuseumPoster - POSTER, FRAMED, "The Family Herald and The Weekly Star", Montreal Canada, " CANADA RALLY TO THE EMPIRE - ANSWERING THE CALL OF THE MOTHERLAND", 1914

From relevant information - "The poster was sent to my Grandmother's father (John Garriock) from Canada. It was a giveaway in a Canadian farming magazine of the time. My Grandmother (Barbara Ross) and Grandfather (Robert Heddle Ross) kept the poster and it eventually came to me. I wish to donate it as a way of remembering them".Poster - panoramic poster, paper, black and white, depicts the "Canadian Army setting sail to join British Forces operating against Germany in the War of Nations". Collection of ships setting sail. Print below illustration. Frame - timber, brown/black stain/paint, cardboard backing to poster, cardboard backing. Glass front.framed item, poster, canada, 1914 -

Moorabbin Air Museum

Moorabbin Air MuseumBook - BATTLE OF BRITAIN, John Foreman, 1988

... BATTLE OF BRITAIN Book BATTLE OF BRITAIN John Foreman Air ... -

Moorabbin Air Museum

Moorabbin Air MuseumBook - THE HARVARD FILE, John F. Hamlin, 1988

... THE HARVARD FILE Book THE HARVARD FILE John F. Hamlin Air ... -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

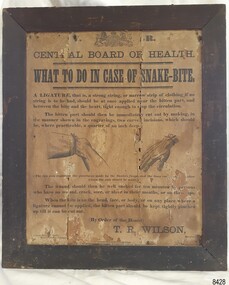

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillagePoster - Snake Bite treatment, T.R. Wilson, Secretary, Central Board of Health, What to do in case of snake-bite, 1865-1881

The poster has the following instructions for the treatment of snake bite:- "A ligature, that is, a strong string or narrow strip of clothing if no string is to be had, should be at once applied near the bitten part, and between the bite and the heart. tight enough to stop the circulation. The bitten part should then be immediately cut out by making, in the manner shown in the engravings, two curved incisions, which should be, where practicable, a quarter of an inch deep. The wound should then be well sucked for then minutes, by persons who have no wound, cut, sore or ulcer in their mouths, or on their lips. When the bite is on the head, face or body, or on any place where a ligature cannot be applied, the bitten part should be kept tightly pinched up till it can be cut out." The poster was authorised by T.R. Wilson, Secretary of Melbourne's Central Board of Health, between 1865 and 1881. It was printed by John Ferres, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1865-1881. The Central Board of Health, Melbourne, was in existence between 1855 and 1889. This poster has significance as an early record of public health instruction issued by the Central Board of Health in Melbourne for the treatment of snake-bite. The materials used to mount and frame the poster are also of significance, with the printing being done on fabric, and the newspaper inserted between the poster and the backboards.Timber-framed rectangular poster with printed instructions for treating a snake bite. The poster is printed on fabric. Between the poster and the backboards is a layer of newspaper, revealed by the damaged fabric. The back of the frame is filled by three vertical timber panels that are strengthened by three horizontal timber slats across the top, centre and bottom. The timbers are fixed in place with nails. The edges of the frame at the back have remnants of paper. Two metal eyelets are inserted into the top edge of the frame. The poster was issued by the Central Board of Health in Melbourne and printed by the Government Printer in Melbourne. It has the British Coat of Arms on top, diagrams and text, plus sections of newsprint.Symbol of [British Coat of Arms] between the letters "V." and "R." Headline "CENTRAL BOARD OF HEALTH" Subheading "WHAT TO DO IN CASE OF SNAKE-BITE" Instructions are printed on the poster. Diagrams include a bite on the knee and bites on the hand. Publisher "Central Board of Health, Melbourne, 28th February ----" "(By Order of the Board), T.R. WILSON, Secretary" "BY AUTHORITY, - - - - - - - - -, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE" Newsprint includes:- "Duties in the bay were put ... --rried out. On ... harbour boat's cr-- ... , and formed of sufficient ... given ... to vessels in distress, and ... life-b- ... the help of a few..." and "last, a Gold English ... engraved -- cove-- to leave it at F.P. ..."flagstaff hill, warrnambool, maritime village, maritime museum, shipwreck coast, great ocean road, central board of health, melbourne, t.r. wilson, secretasry, government printer, john ferres, snake-bite, treatment, first aid, 19th century, poster, government health announcement -

Bendigo Military Museum

Bendigo Military MuseumUniform - BATTLE DRESS, ARMY, Esquire, 1950 and 1981

John Bruce MacCathie. POB: Dalkeith, Scotland. DOB: 4 AUG 1923. WWII: He served in the Royal Navy, Service No C/JX340061. POST WWII: As a member of the British Armed Forces he applied to stay in Australia – the National Archives holds his application form. MARRIAGE: He married Isabel Noel Fulton in 1949, in Vic. AUST. MIL. FORCES: He joined the Aust. Army and served from 1953 to 1977. His number then was 35175 in the Royal Aust. Engineers. His last rank was Sergeant. Returned Service League: He spent some time as a member of the Castlemaine Sub Branch. DEATH: He died 28 JUN 2005. His remains are in the Garden of Remembrance, Springvale, VIC. FAMILY: He was survived by his wife Isabel ( dec 2020) and two children. Ribbons 1. 1939-45 Star 2. Atlantic Star with Rosette, 3. Africa Star with Rosette. 4. Italy Star, 5. Defence Medal, 6. War Medal 1939-45, 7. General Service Medal 1962, 8. Long Service and Good Conduct Medal.1. Jacket - Khaki, woollen. On both arms are Sergeants cloth stripes and a cloth badge for Royal Aust. Engineers. It has eight medal ribbons on left breast. 2. Trousers - Khaki, woollen. Zip fly, no cuffs on ankles. 3. Lanyard - cotton, black. Small loop one end, large loop at other end.Written in jacket is “35175 MacCathie” A tag in jacket shows his Navy no. “C/JX340061” - British Navy.post ww2, uniform, winter, passchendaele barracks trust -

Ballarat Heritage Services

Ballarat Heritage ServicesPhotograph - Architecture, Novar, Webster Street, Ballarat, 02/05/2022

Built in 1885 of red brick, the Webster Street Ballarat mansion was once a private hospital designed by architects E. James & Co. The 900sqm building had eight bedrooms, four bathrooms and five living areas plus a large separate bluestone summer house under the main dwelling. Used as a repatriation hospital after World War One, it was later used by St John of God hospital. In 2018 Ballarat OSM moved into the building. "Novar" is typically Victorian with its faceted wrap around verandah with ornate cast iron filigree lacework. The polychromatic clinker brick banding that spreads across the building's facade is also typical of the Victorian era, as is the use of large bay windows to allow light to fill the mansion's formal reception rooms. "Novar" also has exaggerated chimneys with fine stonework detailing. "Novar" was so named in recognition of Lady Helen Hermione Munro Ferguson (1865 - 1941), the wife of the then Governor general Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson (1860-1934). Lady Munro Ferguson was also the Countess of Novar and founder of the Australian Red Cross movement. In 1918 she was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire for her war work during the Great War. When her husband's term as Governor-General came to an end in 1920, the Munro Fergusons returned to "Novar House"; an Eighteenth Century residence located north of the village of Evanton in Ross, Scotland. After boom turned to bust, Mr. Stephens sold "Novar" to Mr. John Heinz, a wealthy local butcher. He named the building after his home town - Nieder Weisel. In 1919, "Novar" was the first property in Victoria to be purchased by the Red Cross Society for use as a convalescent home for soldiers wounded in battle. Its size, especially after the 1901 two storey rear extension, and its large gardens, made it a perfect place to nurse the wounded. After the war in 1922, "Novar" continued life as a hospital; the Novar Private Hospital. It was sold in 1956 and reverted to a residence, which it remains to this day, only it is no longer known as "Novar", but "Valhalla". Photographs of the house Novar in Webster St Ballarat. novar, webster street, ballarat, nieder weisel -

Clunes Museum

Clunes MuseumPainting, WILL LONGSTAFF, MENIN GATE AT MIDNIGHT, 1927

COPY OF MENIN GATE HELD AT CLUNES R.S.L. MENIN GATE WAS UNVEILED ON SUNDAY JULY 24th 1927. A MEMORIAL TO THE ARMIES OF BRITISH EMPIRE WHO STOOD THERE 1914 - 1918. AND TO THOSE OF THEIR DEAD WHO HAVE KNOWN NO GRAVE. WILL LONGSTAFF WAS SO MOVED HE MADE THE PAINTING WHICH WAS UNVEILED JULY 27th THE PAINTING IS NOW HANGING IN AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL IN CANBERRA.BOROUGH OF TALBOT AND CLUNES.1 FRAMED COPY OF PAINTING "MENIN GATE AT MIDNIGHT" .2 DOCUMENT ENTITLED "THE GHOSTS OF MENIN GATE - THE STORY OF CAPTAIN WILL LONGSTAFF'S GREAT ALLEGORICAL PAINTING" 3. FRAMED COPY OF PAINTING "MENIN GATE AT MIDNIGHT" BY WILL LONGSTAFF.3 BRASS PLATE ATTACHED TO THE WOODEN FRAME BELOW THE IMAGE INSCRIBED -"MENIN GATE AT MIDNIGHT, COPYRIGHT, RESERVED BY WILL LONGSTAFF PRESENTED TO THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA BY LORD WOOLAVINGTON"; A SECOND BRASS PLATE IS ATTACHED TO THE FRAME AT THE RIGHT HAND SIDE INSCRIBED "PRESENTED TO THE MAYOR CR N. C. FOULKES AND COUNCILLORS OF THE BOROUGH OF CLUNES JULY 1929" .1 BRASS PLATE ATTACHED TO THE WOODEN FRAME BELOW THE IMAGE INSCRIBED "MENIN GATE AT MIDNIGHT BY ILL LONGSTAFF Copyright Reserved""local history, illustration, copy, longstaff, sir john -

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and VillagePhotograph - Historical, religious, mid-20th century