Historical information

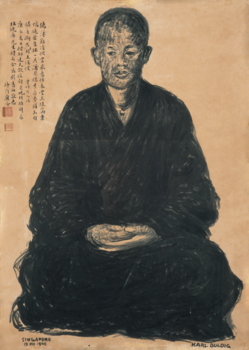

The Buddhist monk Guangqia visited Karl Duldig’s studio on two consecutive days, in the company of the noted Chinese writer, Professor Yu Dafu, a friend of Karl’s. Karl made two portraits of the monk, the first depicting him sitting, and the second in a standing pose. The portraits were drawn using a Chinese brush and Indian ink. Surviving sketches in the Studio’s collection indicate that Karl thought about creating a life-size sculpture later on, but this was not realised.

Guangqia added inscriptions in his own hand to both drawings and stamped them with a red seal. The seated drawing has an inscription in which he quoted from a Buddhist poem, ‘A Contented Mind’ by the scholar Lingfeng of Mt Tiantai.

In the summer I went to visit the Austrian sculptor Duldig with

Professor Yu Da Fu.

My virtue is slight – I cannot accept your offerings and gifts;

I am amply rewarded by the clouds and springs.

Rather than a table laden with pearl-like rice,

I prefer the wind and leaves falling on my bed.

Sitting quietly on my meditation cushion

Is sweeter than the wheat offered by a thousand families.

The pity is that I am gradually growing old;

My bitter journey is not worthy of your offerings.

The second drawing has a quote from a Buddhist poem on the study of Chán (Zen) Buddhism, by the famed Chán master, Dàjiàn Huìnéng (638–713):

The portrait, with its figure positioned on a scroll-like ground and inscription is reminiscent of traditional Zen Buddhist portraiture. In this school of portraiture, which stretched back to at least the thirteenth century, monks were depicted sitting or standing facing the viewer, and typically the monk added an autographic inscription to the portrait. The portraits were often passed from master to disciple, continuing the disciples’ journey of spiritual enlightenment and were revered for their association with remarkable or holy priests. The Buddhist monk, Guangqai who added his inscription and stamp to the drawings would most certainly have been aware of this tradition.

It is likely that Karl was aware of this tradition, one of the points where the studio’s collections of art works from Singapore intersect with the earlier Viennese collections can be found in the Library where a catalogue of an exhibition, 'Ausstellung Ostasiatischer Malerie und Graphik' is held. The Viennese Friends of Asian Art and Culture and the Albertina Museum staged this exhibition of East Asian painting and graphic works in 1932. Such was the internationalism of Duldig’s education in Vienna, that adaption to a new environment and culture in the Straits Settlement was swift, and he was able to interpret the artistic traditions of the place, and make them his own.

It is part of the strength of the collection, that in many cases contemporary supporting documentation for the works of art is available. In this case there is a photograph of the Monk with Yu Ta-fu, and Karl and Eva Duldig, outside the studio at the time the drawings were made.

Ann Carew 2016

Significance

The portraits of Guangqai have national and international aesthetic significance. The works of art demonstrate the artist’s skill in capturing the physical appearance and demeanour of his subject, and his ability to adapt his working methods to incorporate traditional Asian materials and cultural practices. The portrait is one of few examples in Melbourne of a central European modernist artists working in, and engaging with Asia, during this period and it is culturally and aesthetically significant for this reason.

The portraits are also historically interesting in documenting the life and experiences of Karl Duldig in the Straits Settlement (Singapore).

Ann Carew 2016

Physical description

Brush drawing in chinese ink on paper.

Seated Buddhist Monk.

Chinese calligraphy hand written in black ink.

Two red stamps under calligraphy.

Inscriptions & markings

Signed Karl Duldig in l.r. corner.

Dated Singapore 1940 in l.l. corner.

References

- Duldig Studio museum + sculpture garden http://www.duldig.org.au