'Felon families: Stories of women prisoners and their families', Diane Gardiner

Felon Families: Stories of women prisoners and their families

Diane Gardiner

Old Melbourne Gaol

National Trust of Australia (Victoria)

Life in the colony of Victoria during the nineteenth century could be fraught with difficulties for families and, particularly, for women. The problems they encountered in hard times were exacerbated by distance from the support and friendship of their extended families.

Men had greatly outnumbered women since European settlement commenced. To correct this imbalance a great many unaccompanied single women were encouraged to migrate to Victoria during the gold rushes in the 1850s. If unable to find husbands or work, they survived by desperate means such as theft or prostitution. Prostitution in particular represented a threat to the moral well-being of a society which, even more than today, was predicated on a myth of unimpeachable family respectability, with the wife and mother as exemplar. However, for families experiencing the tough conditions of the rapidly developing colony, respectability was often the first casualty. If women found themselves unable to cope, the repercussions for the whole family could be tragic.

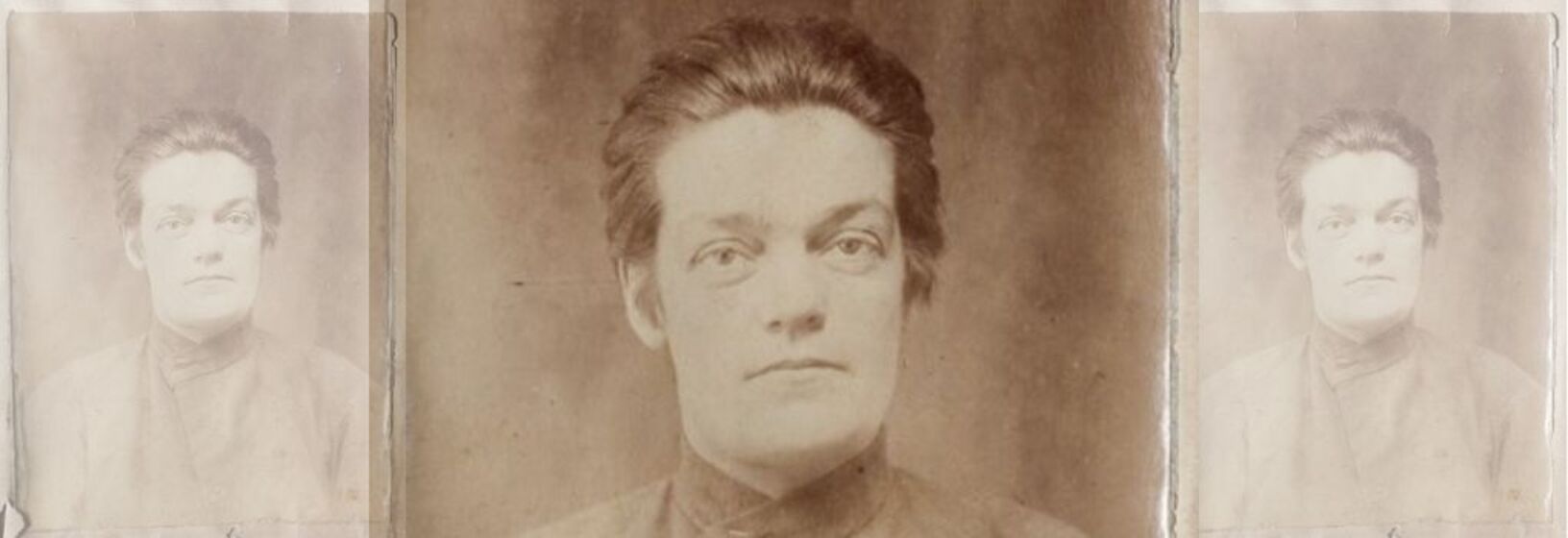

Elizabeth Scott's story illustrates the horrors that a young girl forced into marriage and living in an isolated part of the country could experience. Elizabeth Scott was the first woman hanged in Victoria - at the Old Melbourne Gaol on 11 November 1863.

When Elizabeth was thirteen years old she was coerced by her mother into marriage with Robert Scott, a much older man and an alcoholic. Together they ran a bush inn near Mansfield for ten years. They had five children, of whom three died in infancy.

Elizabeth was supposedly friendly with two local men. David Gedge worked nearby at a staging point for a coach-run between Mansfield and Jamieson. The other man was Julian Cross, an Asian hired by Scott to work as a general hand in the business. While Scott was in one of his drunken stupors, either Gedge or Cross shot him and tried to make it look like a suicide. Elizabeth was not even in the room when the murder occurred; but she, together with the two local men, was arrested.

Victoria's ultra-conservative chief justice, Sir William Stawell, known as the 'hanging judge', presided over the case and condemned all three to hang. At the trial no evidence was given on Elizabeth's behalf. Neither would premier McCulloch commute the sentence. Only the Herald had misgivings: 'There is something unusually terrible in condemning a woman, even though she be unsexed by her crimes, to a sudden and shameful death' (6 November 1863).

The three prisoners were executed together at the Old Melbourne Gaol. Nothing is known of what became of Elizabeth's two orphaned children.

Elizabeth was probably kept in the newly built 1860s Female Ward. It was almost identical in layout to the men's Second Cell block, which is still standing. Women had been held at the Old Melbourne Gaol from 1842 but were not kept apart from the male prisoners until the Female Ward was built 20 years later. Women were occupied with washing, making and repairing their own clothes, and making shirts and waistcoats for male prisoners. They also acted as domestic servants for the governor and his family.

The stories of the unfortunate women who were hanged in the era around the 1890s reflect the desperation that families experienced during that time of severe economic depression. Their stories also demonstrate that sentencing often seemed arbitrary and depended on the persuasion of those in authority.

People like Frances and Rudolph Knorr found life hard in Melbourne during the 1890s depression. Jobs were scarce, there was no state welfare and it was difficult to avoid becoming involved in petty crime.

When Rudolph Knorr was sent to prison in February 1892 for selling furniture being bought on hire purchase, his wife was left pregnant and penniless. She managed by 'baby farming' - looking after children whose mothers could not care for them.

In September 1892 the bodies of three babies were discovered in Brunswick. Frances was arrested and sent for trial in December. The Weekly Times described the 23-yearold woman as 'white and careworn'. She probably suffered from epilepsy.

The public was deeply divided when she was sentenced to be executed. The hangman, Thomas Jones, committed suicide two days before the event. His wife had threatened to leave him if he hanged Mrs Knorr.

Nevertheless, Frances Knorr hanged on 15January 1894. This was the first execution of a woman in Victoria since 1863.

Frances Knorr found little support either among newspapers of the day or among government officials, for they had all come to believe in the deterrent effect of capital punishment. Her execution was intended as a warning to other wayward women. The city's health officer, Dr Neil, told a royal commission in 1893 that, of about 500 post-mortems he had performed on child bodies, more than half indicated murder.

Martha Needle was the next woman to be hanged, also in 1894. Martha was an attractive woman with an apparently kindly disposition, but she was insane by any modern standards. Her friends were shocked when it was discovered she had poisoned her husband, daughters and prospective brother-in-law. She had grown up in a violent and abusive household, and had shown signs of mental instability as an adolescent, but had grown into a beautiful young woman and married at seventeen. After her children's deaths, before she was apprehended, she spent the insurance money on an elaborate family grave which she visited regularly.

She was hanged at the age of thirty. Martha had been raised in an unstable family and wreaked havoc on her own. Her story is unusual in this catalogue of misery, because her crimes arose not out of the severe circumstances of colonial Victoria but from universal, age-old family and personal dysfunction.

Emma Williams' case demonstrates the horrific action that a single mother with no support could be forced to take. The Champion newspaper claimed in October 1895 that the case of Emma Williams would 'exhibit Victoria to the world as the very lowest and most degraded of all civilised communities'. Was the newspaper condemning the society or the criminal?

Emma and her husband arrived in Melbourne in 1893 from Tasmania but things went badly for her. Work was scarce because of the depression; she became pregnant; and her husband died of typhoid. She tried unsuccessfully to give her son to a baby farmer or orphanage, and resorted to prostitution to survive.

In August 1895 the anguished mother drowned her baby son because he was a 'nuisance' and cried when she had clients. Emma was found guilty but her execution was delayed when she claimed, falsely, to be pregnant. Various public petitions against capital punishment were sent to the Executive Council but Emma was hanged on 4 November 1895, aged twenty-seven.

All of these cases illustrate the extreme punishments that could be meted out to women. Yet Janet Dibden, who committed a similar offence, was to avoid the gallows.

Janet had given birth to a large number of children, of whom five died while young. She was living apart from her husband when John Dibden was born on 20 November 1887. Janet gave the baby to Ellen Gardner, a baby farmer, to care for. However, Gardner did not give the baby proper food, starving him and allowing him to become filthy and emaciated. About mid-December the condition of the child was noticed by some outsiders and he was returned to his mother. She continued to neglect him, and John died on 24 December 1887 of starvation. Dibden and Gardner were found guilty of manslaughter. Janet was sentenced to four years gaol and Ellen three years, served at Old Melbourne Gaol. While Janet was in gaol she penned the following poem:

THE BROKENHEARTED MOTHER'S RECITATION

My age is fifty five,

My children their mother have despised;

In this world alone.

No daughter to say,

Dear mother, do come home;

My mother, I love so dear,

I am your son, I wish you were here.

Ellen Kelly had married 'Red' Kelly in 1850. Red was an ex-convict transported from Ireland ostensibly for stealing two pigs. He had settled in country Victoria, prospecting for gold. Later he purchased a small farm but was forced to sell because of debts. The bushranger Ned Kelly was the second of Ellen's eight children. Ellen had little education and was unable to write. Life was not easy.

After Red died she ran a sly grog shop as a means of earning some money. A little known side to the Ned Kelly saga was that Ellen was in the female section of the Old Melbourne Gaol when Ned was hanged on 11 November 1880. She had been convicted of assaulting Constable Fitzpatrick when he had visited her home and harassed her daughter Kate. Ellen was sentenced in the Beechworth Court to three years in gaol for supposedly hitting the constable on the head with a shovel. Even by the standards of the day this was a harsh punishment, made even crueller by the decree that she was not allowed to take the normal course of having her four-month-old baby in prison with her. Her punishment was meant to be a warning to the Kellys and their relatives.

As it transpired, Ned was captured and sentenced to hang while his mother was still serving her sentence. Permitted to visit him before his execution, she told him: 'Die brave, die like a Kelly'. Then Ellen waited in the adjacent building for her son's execution.

The diaries of John Castieau, governor of the gaol between 1869 and 1884, reveal how harsh the conditions were for women prisoners. Nevertheless it was not uncommon for a pregnant, destitute woman to commit a crime so that she could be cared for in the gaol hospital and have her delivery there. Babies under the age of twelve months were allowed to be with their mothers in prison. For these women, conditions outside the gaol were intolerable.

When women left prison, the inequalities, disadvantages and stigma remained. Even the Discharged Prisoners Aid Society refused aid to females, putting them in the same category as drunks. It was to take considerable time to improve conditions for women and to change such attitudes. Many families hid from other family members and their descendants the fact that a family member had been imprisoned or hanged.

Families settling in the new colony had much to contend with. For women the problems were often insurmountable, especially if they were widows with children or were unemployed. Many were forced into prostitution, while others sought solace in drink. When these women ended up in gaol, the cycle of devastation upon the families continued.