Kooramook yakeen: Possum dreaming

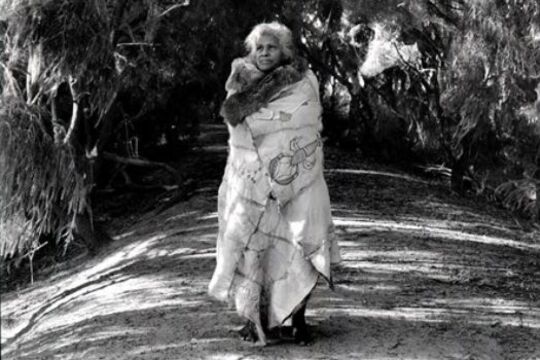

Kooramook yakeen: possum dreaming Culture is the framework through which we connect to our Country, our Belonging. It defines and makes us who we are. Our language, stories, songs, dance, artefacts, cultural knowledge and practices demonstrate our continuing connections. Land, language and identity are fundamental to our Being. To know who you are, and where you come from, is to know your Place. Background Possum skin cloaks were a vital part of Aboriginal peoples lives in pre-European times. Cloaks were used in daily activity, to keep warm, to sleep in and carry our babies. Cloaks were an important trade item. Cloaks were significant in ritual and ceremony. We were buried in our cloaks – ‘wrapped in our Country.’

To make a cloak was a very labour intensive and time consuming process. The skins were gathered; stretched and cured; incised with designs and sewn together with kangaroo sinew; some cloaks were made of 50 or more skins. The designs on the skins depicted stories of clan and Country. There are two surviving 19th century cloaks in the Melbourne Museum collection; the Lake Condah cloak of the Gunditjmara and the Maiden’s Punt cloak of the Yorta Yorta people.

Reclamation and regeneration of possum skin cloak making

In 1999, I attended a Printmaking workshop offered through the Bunjilaka Centre at the Melbourne Museum. It was the initiative of roving curator Lorraine Coutts, in partnership with Australian Print Workshop in Fitzroy.

As part of the workshop we were taken to the Museum to view items from the collection. Our group was taken out the back into a collections room where the staff displayed cultural objects and artefacts from the collection, for us to engage with and study closely. The staff allowed us to wander and look at what we felt inclined to and to ask questions.

After a time, we were called to gather around a large unopened box. As we gathered, the box was opened to reveal the Lake Condah possum skin cloak (collected by the museum in the 1870s). Laid bare before us, no glass display cabinet, no barriers. I was overwhelmed with emotion – awe, respect, love, connection, yearning- all of these emotions swirling around inside of me. Lake Condah is part of my Grandmother's Country.

It seemed, in that moment, that the Old People were standing there beside and around us. I felt as if the illusionary veils of time, space and place had thinned, dissipated and I could reach through and feel them, touch and see the Old People. It was a profound spiritual experience.

The acquisition of knowledge by way of dreams is a phenomenon that is well known and widely accepted in Aboriginal cultures across Australia, and indeed around the world. Rover Thomas’ experience in finding the kurrirr kurrirr is an example of our Aboriginal ways of knowing and learning. ' it came to him in dreams over a period of time’. (I want to Paint, Rover Thomas, edited by Belinda Carrigan, Heytesbury, 2003)

Noongar Elder, Vilma Webb or Wonidgie (Speaker of the Dead), says of the Spirit Journey ‘...dreaming, go on a journey in dreamtime, a chance to look into the future. The Old People would travel this way often and advise the rest of the tribe, as a visionary of the tribe...' (Elders, Peter McConchie, Cambridge University Press, 2003).

After viewing the cloak a vision, a dream, was given from the Old People to us (Vicki Couzens, Debra Couzens, Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm, Maree Clarke).

In my conference paper at the Museums Australia in 2009, I said:

Our story began ten years ago. The Old People sent this story to us. We heard them speak through our hearts to our spirits. They told us what to do, they are still telling us what to do.

Their message, our story, is to return the cloaks to our People, to reclaim, regenerate, revitalise and remember. To remember what those cloaks mean to us and tell the stories of our People and Country. (Museums Australia Conference, VL Couzens, Newcastle, 2009)

Koorramook yakeen – koorramook yana-n – koorramook poorrpa – laka meerreng laka maar. Possum dreaming, possum journey, possum travelling, talking Country, talking people.

wunta yananooroo ngathoongan? Wunta ngeeye ngaken-an? Where are we going? What is our vision?

This dream became, and continues to be, a long and profound spiritual, cultural journey.

Commonwealth Games

In 2005-2006, I was invited to attend a ‘think-tank’ on ideas for the Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony. From this discussion I developed the proposal meerta peeneeyt, yana peeneeyt, tanam peeneeyt kooramook: stand strong, walk strong, proud flesh strong, possum skin cloak, mpyptpk.

On this project we worked with local artists, community and traditional owner groups to create possum skin cloaks which were worn in the Opening Ceremony of the Commonwealth Games. This project sparked a major cultural phenomenon, a renaissance of an almost lost cultural practice. It brought together the largest gathering of Aboriginal people in cloaks in over 150 years to represent their People; clans and communities– all there in unity, One Heart, One Spirit. It was a healing journey for all bringing an all encompassing sense of belonging, togetherness, pride and strengthening of identity.

mpyptpk enabled us to realise the core intent of the Old People through kooramook yakeen: possum cloak dreaming and that was to bring the knowledge, skills and cultural revitalisation of possum cloaks back to Aboriginal people in communities across Victoria and south eastern Australia.

Cultural reclamation and regeneration – the story

Since 2006 Possum skin cloaks have been firmly re-established as a cultural practice across Victoria. In more recent years the word has spread and cloak making has been taken up by other south-eastern groups in Canberra, New South Wales, South Australia and is growing.

The making of possum skin cloaks has a regenerating effect on other cultural practices. This process of making a cloak evokes an interest and quest for seeking knowledge of the ‘old ways’ – how were possums hunted? how were and with what were the skins sewn together? What tools were used ? The making teaches old and new skills.

In a cloak-making workshop, different generations interact and this supports the transference of knowledge, of listening to stories, being given knowledge and responsibilities and the strengthening of family and kinship networks.

Possum skin cloaks were an important part of our ritual and ceremonial life. Today they continue that tradition and are used at Welcome To Country ceremonies, community events in both Aboriginal and mainstream communities; for every day use such as warmth/bedding and baby carriers, naming ceremonies, births, deaths and burials.

Language is central to our cultural knowledge. It is the repository of our cultural knowledge, our laws for living and our kinship systems. Making possum skin cloaks triggers the need to find out the language that relates to possums. The knowledge and stories for hunting, materials, ceremony, dance, song. Communities and individuals have and continue to seek this knowledge and relearn their ‘mother tongue’. Again strengthening pride and identity.

The impact of the revival of possum skin cloaks as a community cultural practice has been significant and profound. The healing experience of a possum skin cloak is immediate, powerful and lasting. However the cloaks are encountered their effect reaches to the person’s spirit, giving strength and healing.

In some communities cloaks are used directly for healing. Cloaks are taken and wrapped around a person who may be experiencing emotional issues. At other times cloaks have been laid across hospital beds for those who are physically ill.

One of the most significant aspects of this cultural phenomenon has been the spiritual healing that occurs. The Commonwealth Games project and other ensuing community workshops have engendered a sense of identity and pride in all and every Aboriginal person who encounters a possum skin cloak.

When a cloak is put around someone’s shoulders, when they are enfolded within, there is a visible and tangible sense of empowerment. Emotions are seen and expressed in smiles, words and actions. Some stand taller, beaming smiles and telling of what they feel. Some will stand quietly, reflecting on their feelings, and others will sit and go within to fully experience what they are feeling.

No one is unaffected.

Conclusion

The Old People continue to paint the picture of our story and lead us where we need to go. As our journey unfolds, we are taking cloak making and all that it embraces out to communities. Providing our experience to reconnect and support those communities with their stories. This is our honour and privilege to do this work and we are humbly grateful for the experience.

Dedicated to our Old People.

Vicki Couzens, 2011