Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this page may contain culturally sensitive information, and/or contain images and voices of people who have died

See story for image details

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Lithograph - George A. Appleton, 'View on the Upper Mitta Mitta', 1865, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This artwork shows culturally sensitive material. Permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria.

Managing the Waterways

Aboriginal people managed the place we now know as Victoria for millennia.

Waterways were a big part of that management. Rivers and waterholes, part of the spiritual landscape, were valuable sources of food and resources, and rivers were a useful way to travel. Thus skills such as swimming, fishing, canoe building and navigation were important.

This lithograph is based on a painting by Eugene Von Guerard of Victorian Aborigines on the Mitta Mitta River with the Bogong Ranges in the background. It harks back to an imagined pristine, more noble, time before colonisation. The Upper Mitta Mitta, in North-Eastern Victoria, was probably the country of Dhudhuroa and Jaitmathang speaking peoples before the new wave of settlers arrived.

Charles Troedel's Chromo-Lithographic Establishment, 1865. 1 print: tinted lithograph ; 26.5 x 36.5 cm. on sheet 38.5 x 53.5 cm.

Lithograph - S. T. Gill, 'Night Fishing', c. 1864, State Library of Victoria

Courtesy of State Library of Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library of Victoria

Uses of Canoes

In Victoria Aboriginal people built canoes out of different types of bark - Stringy Bark or Mountain Ash or Red Gum bark, depending on the region.

Bark was stripped from the tree. It was fired to shape, seal and make it watertight, then moulded into a low-freeboard flat-bottomed craft.

Some canoes were very large, able to seat up to a dozen people. Others were only large enough to hold food. Sometimes canoes were built to last several seasons, other times they were built quickly for just one use. Sometimes, as in this sketch by S.T. Gill, fires would be built inside the canoe.

The Australian Sketchbook, Melbourne, Victoria : Hamel & Ferguson, circa 1864. 1 print: colour lithograph on white paper ; 17.7 x 25.3 cm. on sheet 25.4 x 31.3 cm.

Map - David Payne, Watercraft Map, 2014, Australian National Maritime Museum

Courtesy of Australian National Maritime Museum

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Australian National Maritime Museum

Courtesy of Australian National Maritime Museum

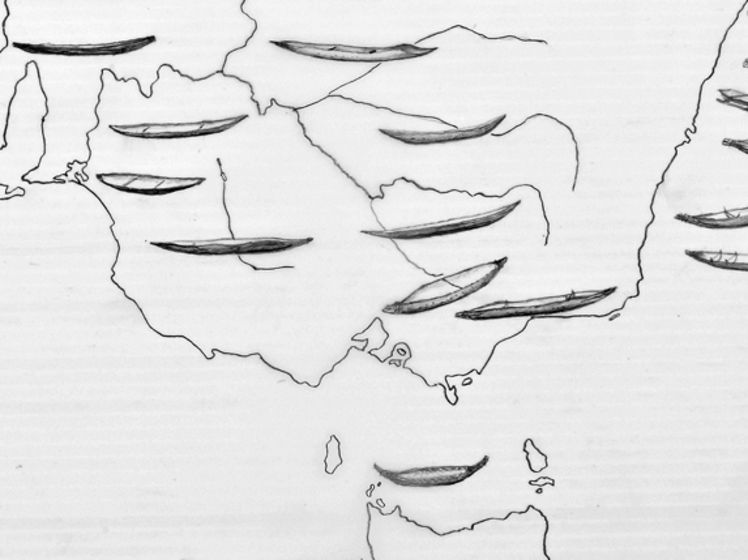

Bark canoes were built all around Australia.

Different types of canoes were constructed in different areas. This map produced by the Australian National Maritime Museum shows the variations in canoe construction geographically.

Map - David Payne, 'Watercraft Map', 2014, Australian National Maritime Museum

Courtesy of Australian National Maritime Museum

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Australian National Maritime Museum

Courtesy of Australian National Maritime Museum

Types of Canoe in Victoria

The inset shows the two major types of canoe built in Victoria.

In the North and North West a flatter style of canoe was constructed using River Red Gum bark. This is sometimes called the ‘Murray River’ style. In the East the form known as ‘Gippsland Style’ had slightly higher freeboard and tied ends and was constructed from the more papery Stringybark and Mountain Ash bark.

Painting - Duncan Elphinstone Cooper, 'Langi Kal Kal', c. 1889, Art Gallery of Ballarat

Courtesy of Duncan Elphinstone Cooper and Art Gallery of Ballarat

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Duncan Elphinstone Cooper and Art Gallery of Ballarat

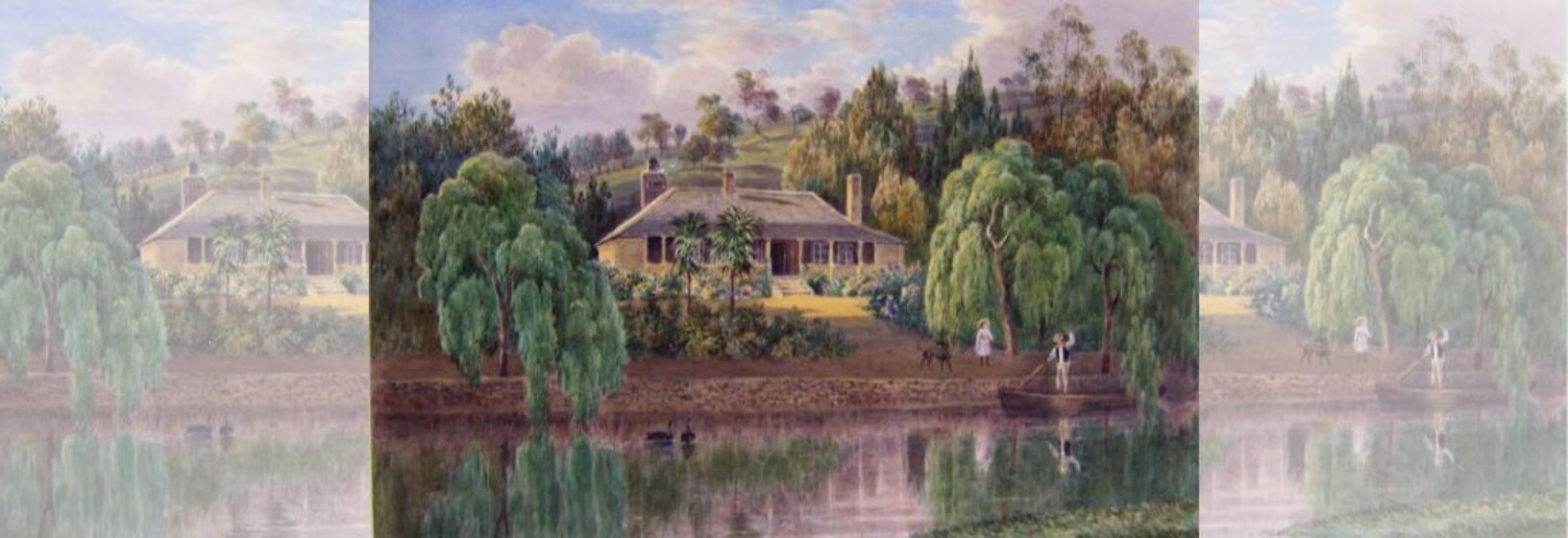

Settlement

River life and a river economy were essential to both pre-colonial and colonial existence.

Aboriginal people relied on waterways and waterholes for their essential resources and food supplies. The colonists, too, needed rivers to feed stock and crops, to transport goods, and for their own survival.

European explorers and colonists arrived in Victoria from the 1830s. The newcomers dispossessed the Aboriginal people of their land, moving swiftly to the best sites, which tended to be close to water resources. The Langi Kal Kal homestead in Central Victoria, depicted here in established form with well-grown European trees, was on the original lands of Wadawurrung (Wathaurung) speaking people who settled seasonally by the Mt Emu Creek.

Watercolour on paper. Purchased with funds from the L.J. Wilson Bequest, 1987.

Painting - Unknown, 'Early Geelong', c. 1860, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This artwork shows culturally sensitive material, permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria.

Adapting to Colonisation

Aboriginal people had to adapt quickly to the impacts of colonisation. It was a time of great change and crisis.

Denied access to resources they had relied on for sustenance, they watched the landscape change as hoofed animals compacted the soil, rivers were dammed, and European farming methods changed the environment. At times it was a violent dispossession. There was resistance. There were massacres. Eventually people were forcibly moved from their traditional lands.

This watercolour of early Geelong from around 1860 shows a group of Aboriginal people in the foreground. There are cattle and homesteads in the background. Geelong was the traditional land of the Wadawurrung (Wathaurung) speaking people.

1 painting: watercolour and Chinese white on buff paper; 29.0 x 46.0 cm.

Map - C.J. Tyers and T.S. Townsend, 'VPRS 8168 Surveyor General’s Department, Port Phillip Branch; P2 Unit 1707, GEOGEN2; Melbourne and the River Glenelg [map]', 1840, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria.

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

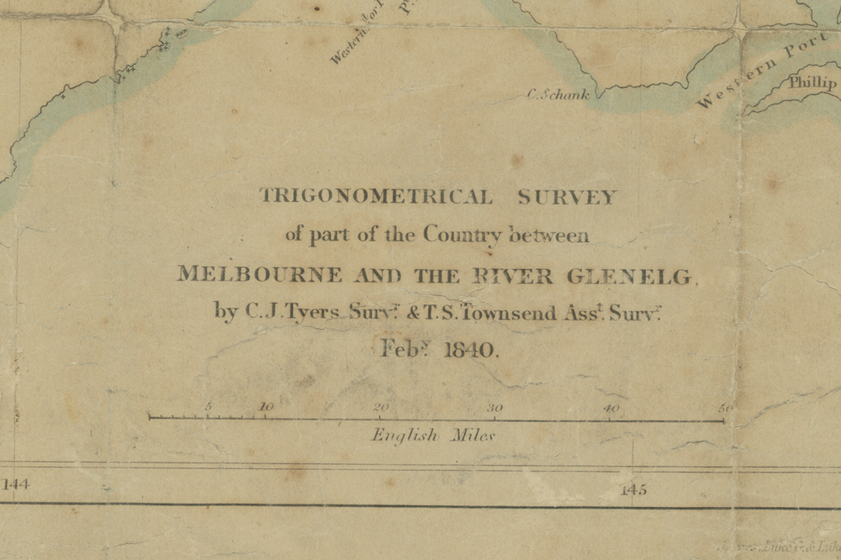

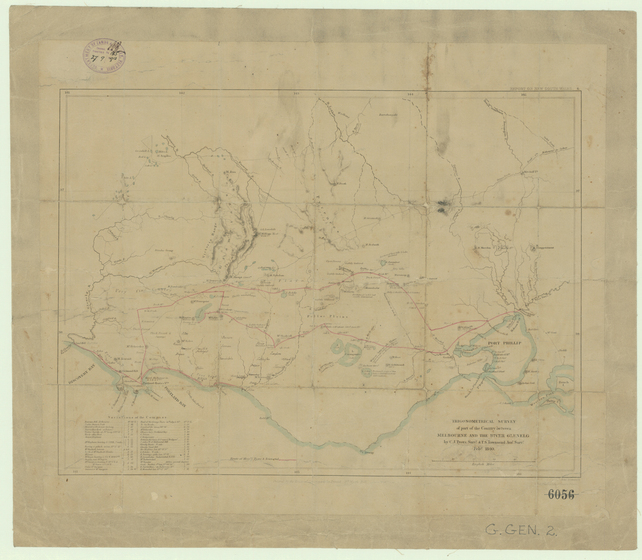

Much of the early exploration of Victoria took place with Aboriginal help. Surveying and geological research relied on Aboriginal guidance and knowledge, particularly to travel along and across rivers.

Of those surveyors needing to cross to Western Victoria in 1840, Charles Sievwright wrote how:

“where from the state of the roads and rivers, I got them [Wadawurrung guides] to render, essential service to settlers and travellers, whose provisions must have been lost, and progress stopped but for their timely aid. The servants of Mr Murray at Colac, and the Surveyors who were proceeding to Portland Bay, can bear testimony to the skill and safety with which their provisions and equipment were transported across the Nar-ra-hil [Moorabool River], in a bark canoe, when without such assistance they must have remained some weeks upon its banks ere the river subsided.[1] “

It is likely that the “Surveyors” referred to in this extract were Charles Tyers and Thomas Townsend, who crossed Victoria between Portland Bay and Port Phillip Bay in 1839-1840.

This rare map of Tyer’s and Townsend’s surveying journey, held by the Public Record Office Victoria, shows rivers, mountains and geological and geographic features. The insets show the area around Geelong, which was the territory of the Wadawarrung (Wathaurung) speaking peoples, and the area around the Grampians-Gariwerd region, which was the territory of the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali speaking peoples.

[1] C. Sievwright, 1 June 1840, in R. Wrench & M.Lakic (eds), Through Their Eyes (Melbourne: Museum of Victoria, 1994) p. 129.

Map - C.J. Tyers and T.S. Townsend, 'VPRS 8168 Surveyor General’s Department, Port Phillip Branch; P2 Unit 1707, GEOGEN2; Melbourne and the River Glenelg [map]', 1840, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

The full map of Tyer’s and Townsend’s surveying journey across Victoria which shows rivers, mountains and geological and geographic features.

Map - C.J. Tyers and T.S. Townsend, 'VPRS 8168 Surveyor General’s Department, Port Phillip Branch; P2 Unit 1707, GEOGEN2; Melbourne and the River Glenelg [map]', 1840, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

The inset shows the area around Geelong and Tyers' and Townsend's Moorabool River crossing point. Faint dates are marked at key points in the surveyors' journey. The Moorabool River was the territory of the Wadawarrung (Wathaurung) speaking peoples.

Map - C.J. Tyers and T.S. Townsend, 'VPRS 8168 Surveyor General’s Department, Port Phillip Branch; P2 Unit 1707, GEOGEN2; Melbourne and the River Glenelg [map]', 1840, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria

The inset shows the area around the Grampians-Gariwerd region, which was the territory of the Djab Wurrung and Jardwadjali speaking peoples.

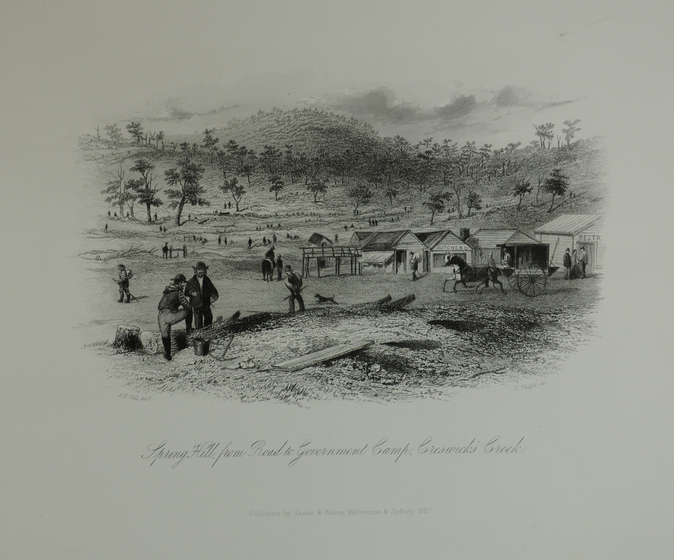

Print - J. Tingle after S.T. Gill, 'Spring Hill from Road to Government Camp, Creswick’s Creek', 1857, Gold Museum Sovereign Hill

Courtesy of Gold Museum Sovereign Hill

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Gold Museum Sovereign Hill

Gold Fever

The gold rush of the 1850s devastated Victoria’s rivers and waterways and brought an influx of people into Aboriginal territory.

Gold was found by creek and river beds, those still flowing and those ancient and buried in the ground. Miners camped and congregated by the waterways and in the forests, digging them up and changing them forever. Creeks were churned up and dammed, and entire river beds diverted or washed away. Forests by the mining camps were denuded, chopped up to provide wood for fires and shelter. The basic resources Aboriginal people relied on were destroyed in the fever to find gold.

Victorian Aboriginal people adapted to the gold rush in many ways, selling possum skin cloaks to miners, cutting bark for shelter, guiding miners to the gold fields and in some instances finding and fossicking for gold themselves. Aboriginal labour also became valued on farms and in industry to fill in the gaps as huge numbers of workers left to find their fortune on the gold fields.

Published by Sands & Kenny, Melbourne & Sydney, 1857

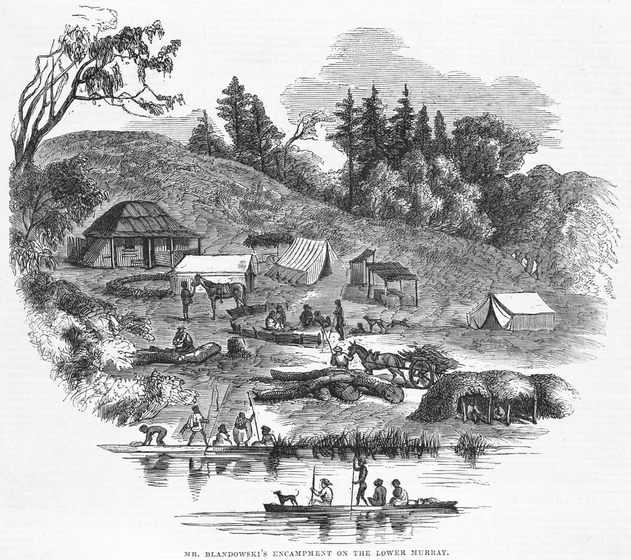

Print - George Slater, 'Mr. Blandowski's Encampment on the Lower Murray', 1858, State Library of Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This artwork shows culturally sensitive material, permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library Victoria.

Ferrying Services

Aboriginal people offered ferrying services to the newcomers.

Hubert De Castella described how Aboriginal people guided large numbers of people, cattle and supplies across the Murray River in the 1850s. In particular he noted the ease it afforded the colonists and also the economic benefits Aboriginal people derived from exercising their entrepreneurial skills.

'Crossing the Murray, which is half a kilometre wide at that spot [junction of the Murray and Darling], was a large number of savages, [who] were camped on the river banks and had boats ready to help the travellers cross.' [1]

This engraving depicts the explorer and geologist William Blandowski’s encampment on the Lower Murray, near the junction of the Murray and Darling Rivers, in the 1850s. In it, three Aboriginal Australians are depicted transporting a white person in a canoe, along with a dog. Before European contact the confluence of the Murray and Darling was probably the country of the Yuyu speaking people, but by 1858 had been claimed by the Marawara, also known as Yaako-Yaako or Weimbio speaking people, who may be the people depicted here.

[1] H.D Castella, Australian Squatters, trans. CB Thornton-Smith (Melbourne: MUP, 1987) p. 128.

1 print: Wood engraving, published in The Illustrated Melbourne news. Melbourne : George Slater, February 6, 1858.

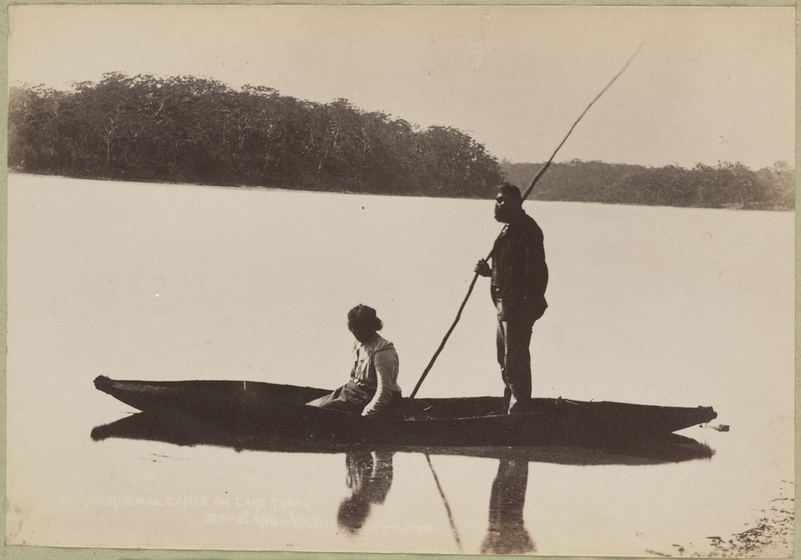

Photograph - Charles Rudd, 'Aboriginal Australian Man and Woman in Canoe on Lake Tyers, Gippsland, Victoria', 1892-1902, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This photograph shows culturally sensitive material, permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria.

Valuable Skills

Aboriginal people could make canoes very quickly. But to do so required specific technical knowledge.

And it wasn’t just the making that was important. The ability to steer and navigate canoes, understanding the rivers and the currents, and confidence in and on the water, were all valuable skills in the 1800s.

Alfred Howitt, who conducted geological research in Gippsland in 1875, described in his journal how he depended on Aboriginal guides to construct and pilot vessels for ferrying the exploration team across rivers, and how they delivered vital stores and provisions to forward positions. He wrote effusively of their efficiency and inventiveness.

This photograph depicts an Aboriginal man and woman in a canoe on Lake Tyers, in Gippsland. It was taken towards the end of the 19th century, probably between 1890 and 1901.

The canoe is the tied end style or ‘Gippsland style’ of bark canoe.

The Lake Tyers Mission was founded in the 1860s for the Gunai/Kurnai people of South Eastern Victoria. By the time this photograph was taken, Aboriginal people from around Victoria were moving or being moved to Lake Tyers.

Photograph - 'On J. H. Kerr's Station', 1849, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Farm Transport

To understand how important rivers were for transport we need to cast ourselves back into the 19th century to a time before bridges and cars.

When rivers flooded they became major barriers to trade and movement.

This photograph of John Hunter Kerr’s station in 1849 shows the ute of the day – a horse and cart.

John Hunter Kerr was an early photographer and a pastoralist, taking property on the Loddon Plains near Boort, near the border of Dja Dja Wurrung and Wemba Wemba language group territories. Aboriginal people lived on and near his land. His now significant historical photographs taken in the 1840s and 1850s of Aboriginal people are held by the State Library of Victoria.

When this photograph was taken, one of Kerr’s neighbours, the pastoralist Fredric Godfrey, a squatter of Boort on the Loddon River, was relying on Aboriginal labour on bark canoes. Godfrey was struck by the usefulness and utilitarian nature of Aboriginal canoes, especially noting in his journal the debt owed to the Aboriginal water carriers who rescued ‘two tons of trussed hay in a fine canoe made by the blacks’ on one occasion in September 1852. He added: ‘The Aboriginals were often sent across by canoe for urgently needed goods – flour, tea, sugar, tobacco and the like, which were loaded onto waiting drays.’[1]

[1] Frederic Godfrey (c.1851) cited in F. Stevens, Smoke from the Hill (Bendigo: Cambridge Press, 1969) p. 28.

1 photograph: salted paper; 14.2 x 21.7 cm.

Photograph - John Henry Harvey, 'Smith’s Crossing, Yea River, Toolangi', c. 1875-1938, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Flooded Creeks

For colonists, the movement of mail, stock and goods was vital.

When rivers were low, they could be forded. When rivers flooded and the water level got too high, Aboriginal people would often be employed to ferry goods by canoe. This offered an efficient and safe mode of river pilotage, particularly in remote areas where no other means of transportation was available.

Godfrey described in about 1851 how rivers such as the Loddon, in central Victoria, were prone to flooding and how one year ‘All the country on both sides of the Loddon was flooded, and the wagons could get no nearer than four miles from the homestead, so supplies had to be brought in by bark canoe.’[1]

In 1859 when the waters of Joyce’s Creek at Avenel, near Seymour, rose 20 feet after a flood of the Goulburn River, the Argus reported that ‘passengers had to be ferried across one at a time in a native canoe.’[2]

[1]Quoted in F Stevens Smoke from the Hill, (Bendigo, Cambridge Press 1969) p.28.

[2]The Argus, Tuesday 1 February 1859, p.5.

Transparency: toned glass lantern slide; 8.5 x 8.5 cm.

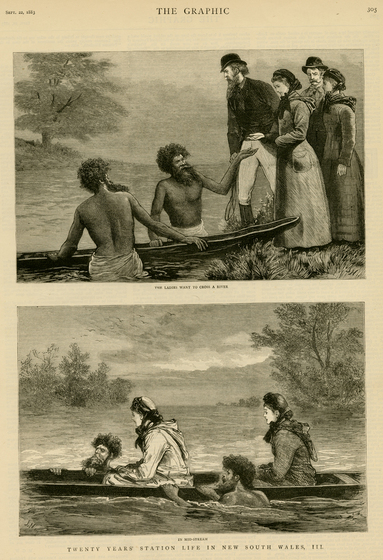

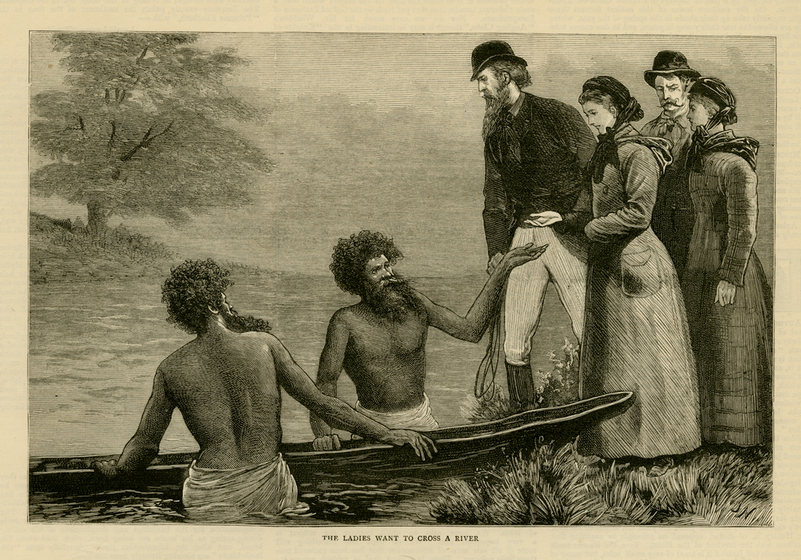

Print - 'The Ladies Want to Cross a Stream; In Mid-stream', 1883, Art Gallery of Ballarat

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Fear of Crossing

Europeans saw canoes as frail craft, low to the water, nothing like the sturdy wooden boats they were used to. It took some convincing to get Europeans into them.

This illustration from the London based magazine The Graphic depicts a scene from station life in New South Wales in 1883. Aboriginal men are ready to guide two European women across the river on a canoe. The associated story acknowledges that the Aboriginal assistance is indispensable:

“the ladies wish to cross the river, but they are a little uneasy at the sight of the boat, and of the ebony-skinned mermen who are acting as attendants. But the truth is these blackfellows are indispensable. The boat is only a frail bark canoe, and to keep this from upsetting the balance must be very exactly maintained. Few Europeans possess the delicacy of touch and sight requisite for this, so the safest way, especially for ladies who cannot swim, is to be piloted by a couple of blackfellows, one swimming on either side of the canoe. The natives are such perfect swimmers that they can swim with both hands and feet tied together, and even if the boat were to upset its fair freight would be quite safe in the hands of these faithful black escorts.”[1]

[1]‘Station Life in New South Wales’, The Graphic, 22 September 1883, p.291.

Illustration taken from 'The Graphic', wood engraving on paper. Purchased with funds from public donation, 2014.

Print - 'The Ladies Want to Cross a Stream', 1883, Art Gallery of Ballarat

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Fear of Crossing

Illustration taken from 'The Graphic', wood engraving on paper. Purchased with funds from public donation, 2014.

Print - 'The ladies want to cross the stream', 1883, Art Gallery of Ballarat

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ballarat

Fear of Crossing

Illustration taken from 'The Graphic', wood engraving on paper. Purchased with funds from public donation, 2014.

Functional Object - 'Woi wurrung, Yarra Canoe', c. 1860, Museum Victoria

Courtesy of Museum Victoria and Benjamin Healley

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Digital reproduction copyright of Benjamin Healley

Courtesy of Museum Victoria and Benjamin Healley

Permission to use these photographs was kindly given by Elders of the Wurundjeri Tribe Land & Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated

Woi wurrung Bark Canoe

This rare artefact is the only remaining 19th century Aboriginal canoe from the Melbourne region.

It was collected by the Buchan family in Kew, Victoria, probably from the banks of the Yarra River in Studley Park, in the 1870s. It is difficult to know when it was built.

The canoe is made from the bark of the Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans). It is therefore probable that the canoe was made in the hills east of Melbourne, and brought down the Yarra River, a distance of over 50 kilometres.

The Yarra River was the territory of the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurrung speaking people. By the 1870s the Wurundjeri and many other clans of the Woi wurrung had settled at Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve in the Yarra Ranges near Healesville, 65 kilometres east of where the canoe was found.

The canoe may have been built by people from Coranderrk and left on the river, or it may have been built before Coranderrk was established. The canoe could well have been sitting near the banks of the Yarra River for some years before being collected and stored by the Buchans.

The canoe incorporates a European technology - hoops from a barrel have been used to hold the bark. Possibly the Aboriginal makers used these hoops, combining a European material with the traditional design. Or they may have been added by the collector.

More information is available on the Museum Victoria Collections website at: http://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/items/199797

Item measurements: 32 cm (height) x 61.5 cm (width) x 451.5 cm (length)

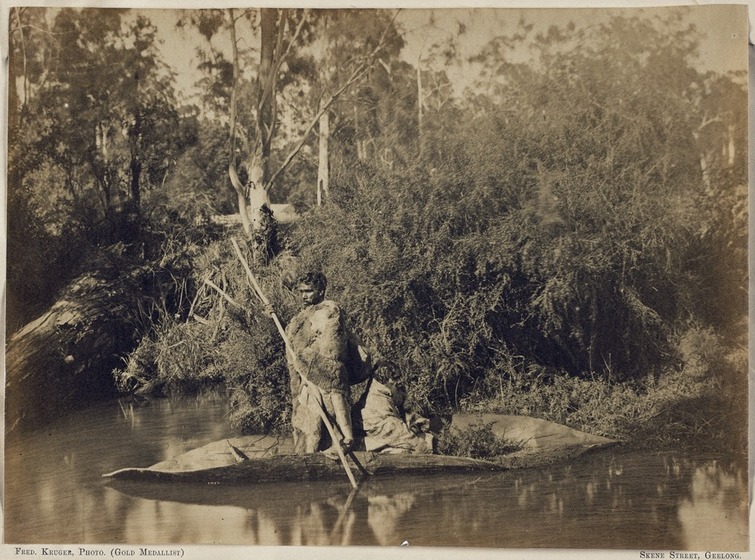

Photograph - F. Kruger, 'Natives and Bark Canoe', c. 1870, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This photograph shows culturally sensitive material. Permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria. Permission to use this photograph was kindly given by Elders of the Wurundjeri Tribe Land & Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated.

Bark Canoe, Coranderrk

Different styles of canoe were built in Victoria. This photograph depicts an inland, flatter, ‘Murray River style’ canoe.

This photograph by Fred Kruger was probably taken on Badger Creek, at Coranderrk, near Healesville in the Yarra Valley east of Melbourne, at around 1870.

Coranderrk, a reserve set up for Aboriginal use by the Victorian government in 1863, was founded on the traditional lands of the Woi Wurrung speaking people, at the instigation of two prominent Wurundjeri leaders Simon Wonga and William Barak. Aboriginal people from all around Victoria were either sent or moved voluntarily to Coranderrk as the process of dispossession forced them from their traditional lands, so the two people in this photograph may have come from river communities elsewhere in Victoria. By the mid 1870s, when this photograph was probably taken, Coranderrk had become a productive farming community.

Photograph: albumen silver; 20.0 x 27.2 cm. approx. on mount.

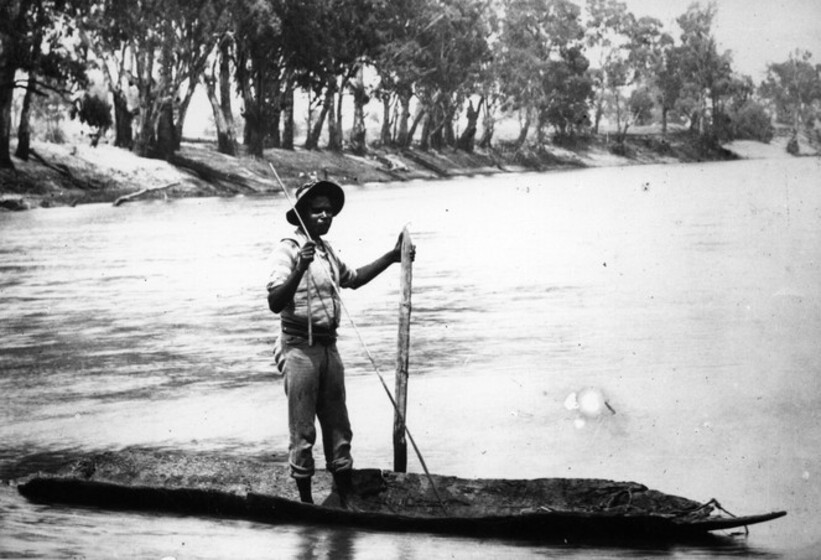

Photograph - 'Alowidgee, Maloga, New South Wales', Museum Victoria

Courtesy of Museum Victoria, Nancy Cato Collection (XP2441)

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of Museum Victoria, Nancy Cato Collection (XP2441)

This photograph shows culturally sensitive material. Permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, Museum Victoria. Permission to use this photograph was kindly given by Elders of the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation.

Alowidgee, Maloga, New South Wales

This photograph of Alowidgee on a canoe was taken at the Maloga Mission, near modern day Barmah, on the banks of the Murray River on the New South Wales side, probably in the late 19th century.

He is steering a flat canoe made in the ‘Murray River style’, probably from River Red Gum bark. Today the nearby Barmah-Millewa Forest forms the largest River Red Gum forest in the world.

Alowidgee was a Yorta Yorta man. The Maloga Mission was founded by European missionaries in 1874 and people of the Yorta Yorta Nation and other tribal groups from the Murray River region were moved here. In 1889 most of the residents of Maloga relocated to nearby Cummeragunja in protest at the strict religious rules of Maloga.

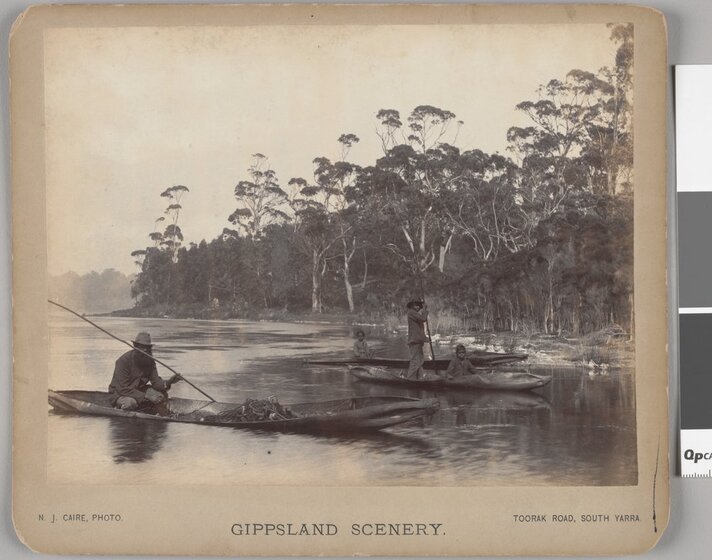

Photograph - N.J. Caire, 'Native Bark Canoes', c. 1886, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This artwork shows culturally sensitive material, permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria.

Both men and women were proficient on canoes.

At Moe (in central Gippsland, in eastern Victoria), one European over-landing party in the 1870s, who were ‘afraid to cross the creek on account of the flood and having eaten all their provisions’ received relief from a female Aboriginal guide whose exceptional bush and canoe skills the travellers depended upon for their very lives. Having heard the desperate travellers ‘cooeeing’ the unidentified Aboriginal heroine crossed treacherous floodwaters twice over ‘with a very welcome parcel of damper, tea, sugar and meat’. The travellers fearing they would ‘die by starvation’ and encircled by rising flood waters elected to use the Aboriginal canoe and crossed the floodwaters safely. [1]

This photograph, taken in Gippsland at around 1886, shows a man, two boys and a girl using canoes constructed in the ‘Gippsland style’ of canoe, which had with a higher freeboard than the flatter ‘Murray River style’ used inland, and where the ends of the canoe were tied up with bark.

[1] G. Dunderdale, The Book of the Bush. (London: Ward and Lock, 1898) p.280.

1 photographic print: albumen silver; 15.0 x 20.5 cm. approx., on mount.

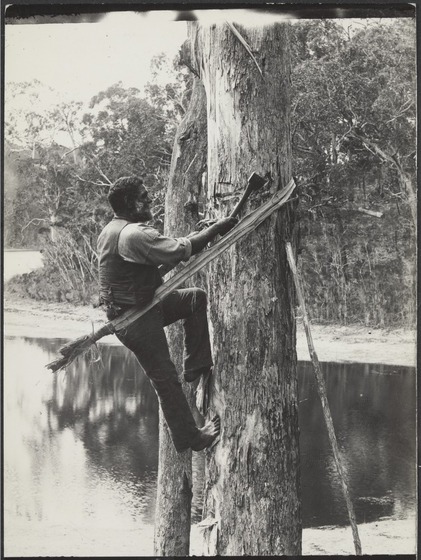

Photograph - Howard Decimus Bulmer, 'Andrew Chase Cutting Bark from a Tree with a Tomahawk, Secured to Tree with Bark', 1936-1937, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

This photograph shows culturally sensitive material, permission to publish must be sought from the collection holder, the State Library of Victoria.

Bark Cutting

Because of their acknowledged skill, Aboriginal bark-cutters were often hired by colonists, gold miners and squatters in the 1800s.

Bark was a useful commodity in the colonial period for roofing and furniture as well as canoes.

The first stage of building a canoe was to strip the bark from a living tree without killing it.

This photograph from 1936 or 1937 taken at the Lake Tyers Mission, in Gippsland, shows Andrew Chase cutting bark from a tree with a tomahawk. He is secured to the tree with bark.

By the time this photograph was taken the Lake Tyers Station was one of the few government Aboriginal reserves left operating in Victoria. In 1917 the Victorian Government introduced a policy of concentrating Aboriginal people at Lake Tyers. Many residents of the former missions at Ramahyuck, Ebenezer, Condah and Coranderrk were transferred here. Most of these former reserve lands were then turned into soldier settlement blocks for returned servicemen of World War 1. Aboriginal returned servicemen, however, were not permitted to settle in them.

Photograph: gelatin silver; 16.6 x 10.8 cm. approx

Photograph - 'On the Loddon', 1872, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Rivers

Both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people appreciated the beauty of rivers.

Rivers were also boundaries, often demarcating the territory of different Aboriginal clan groups.

This picture was taken in 1872 on the Loddon River. Before colonisation the Loddon River was lived on and managed by the Dja Dja Warrung (Upper Loddon) and Wemba Wemba (Lower Loddon) speaking peoples. Colonisation had a rapid impact in Central Victoria and by the 1870s few Aboriginal people remained living tribal lifestyles on their traditional land.

In 1872 a Dja Dja Wurrung man known as ‘Tommy Clarke’ or ‘King Tommy’, whose tribal name was Yereep or Equinhup, was the last known tribal inhabitant of the Upper Loddon river area. He adapted to settlement and lived alongside the gold miners and farmers, and was known locally as “the last King of the Loddon.” A newspaper report of September 1871 notes he brought his bark canoe to the celebrative festive opening of the Laanecoorie Bridge on the Loddon. [1]

[1] ‘Laanecoorie Bridge’, Tarnagalla Courier, 30 September 1871.

1 photographic print: albumen silver; 18.0 x 24.9 cm., on page 29 x 23 cm.

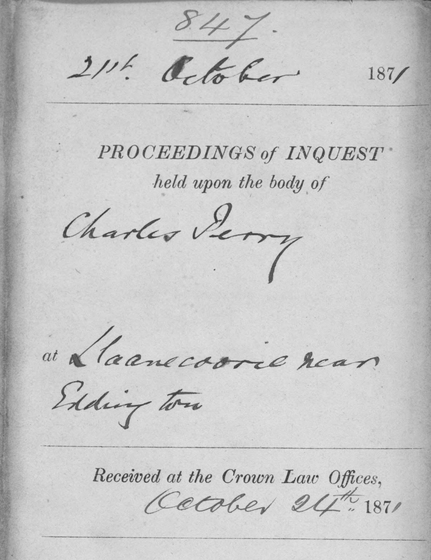

Document - 'Inquest into the Death of Charles Perry, Front Page', 21 October 1871, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria (VA 2889 Registrar General’s Department (Victoria), VPRS 24/ PO Unit 260, Inquest Deposition Files, Item: 1871/847)

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria (VA 2889 Registrar General’s Department (Victoria), VPRS 24/ PO Unit 260, Inquest Deposition Files, Item: 1871/847)

Europeans Drown

When Europeans tried their hand at operating bark canoes it led at times to tragic deaths by drowning, as many could not swim.

In 1871 a young man called Charles Perry drowned trying to cross the Loddon River at Laanecoorie in a bark canoe which had been built and used by a Dja Dja Wurrung man known as Tommy Clarke or ‘King Tommy’.

The inquest into Perry's death found he died accidentally.

Further Information

TRANSCRIPT, Front Page

21 October 1871

PROCEEDINGS of INQUEST held upon the body of Charles Perry at Llaanecoorie near Eddington.

Received at the Crown Law Offices 24 October 1871.

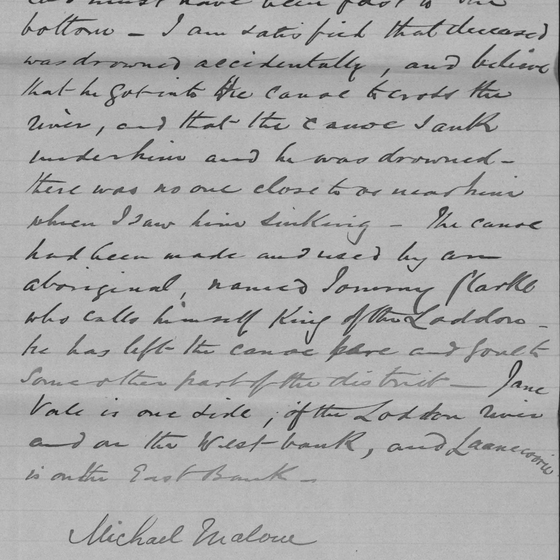

Document - Michael Malone, 'Inquest into the Death of Charles Perry, Extract', 21 October 1871, Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria (VA 2889 Registrar General’s Department (Victoria), VPRS 24/ PO Unit 260, Inquest Deposition Files, Item: 1871/847, Llaanecoorie, near Eddington)

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of State of Victoria through Public Record Office Victoria

Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria (VA 2889 Registrar General’s Department (Victoria), VPRS 24/ PO Unit 260, Inquest Deposition Files, Item: 1871/847, Llaanecoorie, near Eddington)

Europeans Drown

Extract of the deposition of Michael Malone, inquest into the death of Charles Perry, 1871.

Further Information

TRANSCRIPT, Extract

“I am satisfied that deceased was drowned accidentally, and believe that he got into the canoe to cross the river, and that the canoe sank under him and he was drowned. There was no one close to or near him when I saw him sinking. The canoe had been made and used by an aboriginal, named Tommy Clarke who calls himself King of the Loddon. He has left the canoe here and gone to some other part of the district. Janevale is one side of the Loddon River and on the West bank, and Laanecoorie is on the East Bank.

"Michael Malone.”

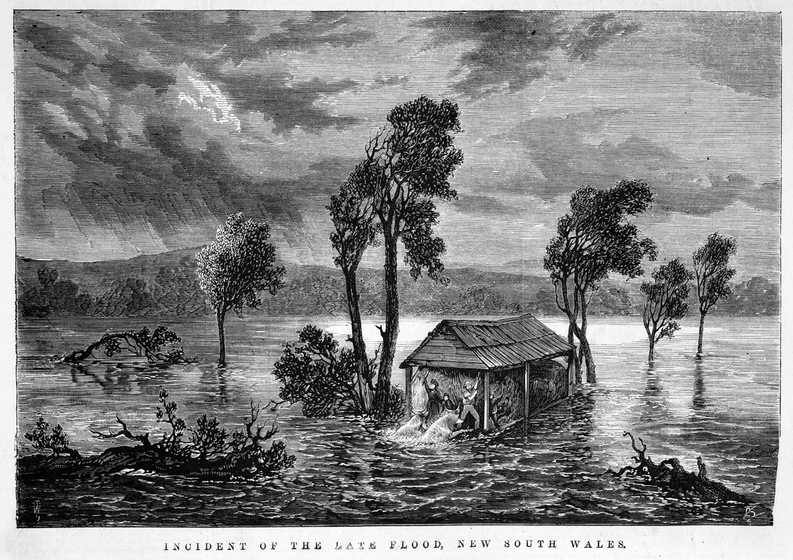

Print - Samuel Calvert, 'Incident of the Late Flood, New South Wales', August 13, 1870, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Great Rescues

Heroic stories of Aboriginal people rescuing Europeans during floods abound.

The most famous account of bravery on bark canoes is from the 1852 flood of Gundagai, in New South Wales, when the Murrumbidgee River overflowed, killing almost 100 people in one of Australia’s largest natural disasters.[1] Four Wiradjuri people played a vital role in rescuing townsfolk from certain death with their bark canoes. Singlehandedly, Yarrie, who was reported as being ‘willing to run any risk to give assistance’, rescued 49 people using his canoe to pluck them one or two at a time off rooftops.

In these times, skill with a canoe was crucial. But in swirling floodwater, no matter how skilled at watercraft you were, going out on a canoe was a great risk. Even more so when, as in some accounts, the Aboriginal rescuer would put the European on the canoe and jump into the floodwater to steer the canoe by swimming with it. In the Orbost district, an Aboriginal named Joe Banks rescued a sick non-Aboriginal man during the floods by ‘making a canoe out of a sheet of bark from the roof and placing the sick man in it, swam through the turbulent waters, towing the canoe and its helpless occupant to safety.’ [2]

This engraving shows a flood in Bodalla, NSW, 1870. Mr. Michael Bell and his family took refuge in the barn after his house was swept away by the flood waters; the barn was full of wheat and so floated down river; the family is shown beating off two bullocks that tried to come on board.

[1] S. Wardiningsih; ‘Remembering Yarrie: An Indigenous Australian and the 1852 Gundagai Flood. Public History Review, vol.19 (2012) pp.120-129.

[2] Cited in ‘Personalities and Stories of the Early Orbost District' (R.H.S.V Ms, 1972).

Samuel Calvert, engraver, wood engraving, published in 'The Illustrated Australian News', August 13, 1870.

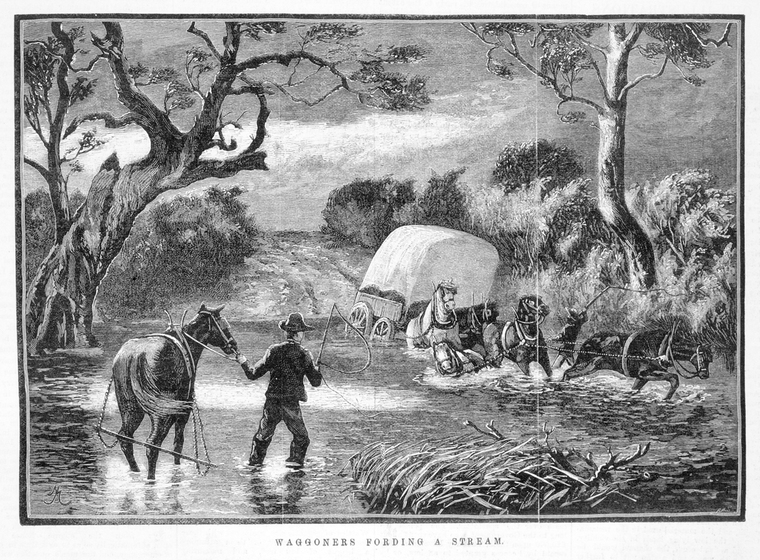

Print - F.A. Sleap, 'Waggoners (sic) Forwarding a Stream', 24 January 1883, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Offering Assistance

Some accounts of assistance offered across rivers emphasise the water skills possessed by Aboriginal people in contrast to the hapless European newcomer.

They also can be intriguingly personal, showing unexpected interactions between the colonisers and the Aboriginal people they had usurped from their lands.

In 1867 a Mr McLachlan, who couldn’t swim, lost control of his horse when crossing the flooded McAllister River in Gippsland, ending up stranded on one bank with his horse on the other. A local Aboriginal man, ‘Billy’, finding the riderless horse, went in search of the rider and found McLachlan puzzling how to get across.

‘Billy, after signifying his pleasure at meeting McLachlan alive, speedily solved the difficulty by making a canoe from the bark of an adjacent tree, wherewith to cross the river. Before getting on board, McLachlan considered it his duty to inform his black friend he could not swim. ”Then you take off ‘em boots,’ says Billy; ‘if ‘em go down, you then swim like ‘em duck.” [1]’

A little time later, when the hastily made canoe started to split, Billy advised McLachlan that if the boat breaks apart he would try to save him, but that McLachlan should not catch him too hard around the head or neck. Fortunately, and by ‘skilful management’ on Billy’s part, they made it to the other side.

[1] The Argus, Thursday 17 October 1867, p.7.

Wood engraving published in 'The Illustrated Australian News'. Melbourne: David Syme and Co. January 24, 1883.

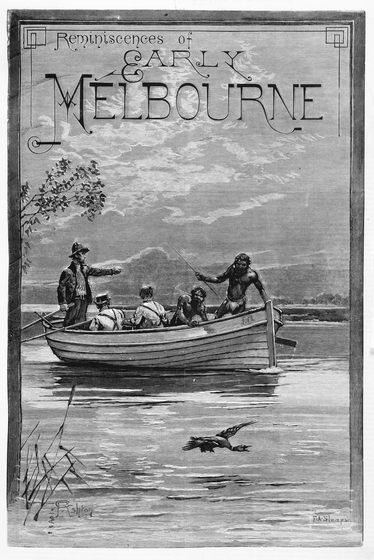

Print - F.A. Sleap and G.R. Ashton, 'Reminiscences of Early Melbourne', 25 June 1887, State Library Victoria

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

Courtesy of State Library Victoria

Forgetting

The knowledge of colonial Victoria’s reliance on Aboriginal people’s skills and technology fell out of historical accounts in the 20th century, untaught and forgotten.

But the diaries, letters, records and newspapers still tell the story if we take the time to read them.

Colonial anecdotes of rescues, ferrying, trade and transport using Aboriginal people's expertise and Aboriginal bark canoes, are coated in the colonial perspectives of the writers, but show a depth and diversity of interactions on Victoria’s rivers between Aboriginal and non Aboriginal Australians.

They tell that humble bark canoes, and the people who made them and navigated them, saved people’s lives and helped make Victoria prosperous.

Wood engraving published in Supplement to the 'Illustrated Australian News'. Melbourne : David Syme and Co. June 25, 1887.