Showing 21 items

matching roads, themes: 'a diverse state','aboriginal culture','built environment','creative life','gold rush','service and sacrifice'

-

Rippon Lea Estate

... to the comforts of the home counties. The same year Frederick married Marian Australia Rolfe, and they rented a house in Alma Road, St Kilda. A decade later, Frederick was able to begin what was to become a life-long project with the purchase of over twenty acres ..."Do you remember the garden in which you grew up, or the part the backyard played in your family life? Imagine if you had actually grown up in one of Australia's finest gardens.

Created in the English-landscape tradition which traces its roots back to Capability Brown and Humphry Repton, Rippon Lea is one of Australia's most important historic homes, exemplifying the lifestyle of wealthy families living in 19th and 20th century Australian cities. Although its architecture and that of its outbuildings is impressive, it is the mansion’s gardens, which are truly remarkable, both for their landscape qualities and because they have survived many threats and changes in the past 130 years.

Today, the amenities offered by a typical garden are still greatly valued: a safe place for children to play, somewhere to dry the washing, a plot for vegetables and a flower garden that adds colour and produces blooms for the home. Today as then, the scale differs but the experience of owning a garden - with its balance of utility and ornament - is essentially the same.

The National Trust of Australia (Victoria) now runs Rippon Lea as a museum, conserving the architecture and the landscape, and presenting the social history of the owners and their servants. Visitors to Rippon Lea enter a mansion preserved as the Jones family lived in it after their 1938 modernisation. In the pleasure garden the Sargood era is evoked by the staging of a range of performing arts events including opera, theatre, chamber music and outdoor activities."

The text above has been abstracted from an essay Solid Joys and Lasting Treasure: families and gardens written by Richard Heathcote for the publication The Australian Family: Images and Essays. The entire text of the essay is available as part of this story.

This story is part of The Australian Family project, which involved 20 Victorian museums and galleries. The full series of essays and images are available in The Australian Family: Images and Essays published by Scribe Publications, Melbourne 1998, edited by Anna Epstein. The book comprises specially commissioned and carefully researched essays with accompanying artworks and illustrations from each participating institution.

-

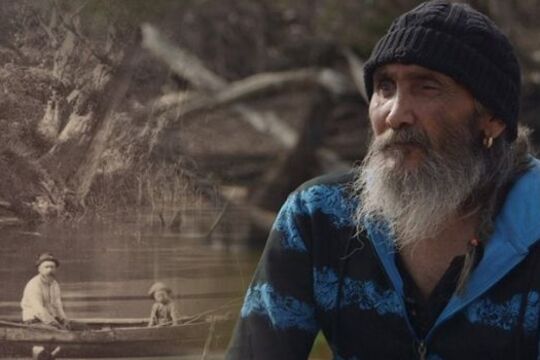

Seeing the Land from an Aboriginal Canoe

... Print: J. Tingle after S.T. Gill, 'Spring Hill from Road to Government Camp, Creswick’s Creek', 1857... Victoria in 1840, Charles Sievwright wrote how: “where from the state of the roads and rivers, I got them [Wadawurrung guides] to render, essential service to settlers and travellers, whose provisions must have been lost, and progress stopped ...This project explores the significant contribution Aboriginal people made in colonial times by guiding people and stock across the river systems of Victoria.

Before European colonisation Aboriginal people managed the place we now know as Victoria for millennia. Waterways were a big part of that management. Rivers and waterholes were part of the spiritual landscape, they were valuable sources of food and resources, and rivers were a useful way to travel. Skills such as swimming, fishing, canoe building and navigation were an important aspect of Aboriginal Victorian life.

European explorers and colonists arrived in Victoria from the 1830s onwards. The newcomers dispossessed the Aboriginal people of their land, moving swiftly to the best sites which tended to be close to water resources. At times it was a violent dispossession. There was resistance. There were massacres. People were forcibly moved from their traditional lands. This is well known. What is less well known is the ways Aboriginal people helped the newcomers understand and survive in their new environment. And Victoria’s river system was a significant part of that new environment.

To understand this world we need to cast ourselves back into the 19th century to a time before bridges and cars, where rivers were central to transport and movement of goods and people. All people who lived in this landscape needed water, but water was also dangerous. Rivers flooded. You could drown in them. And in that early period many Europeans did not know how to swim. So there was a real dilemma for the newcomers settling in Victoria – how to safely cross the rivers and use the rivers to transport stock and goods.

The newcomers benefited greatly from Aboriginal navigational skills and the Aboriginal bark canoe.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images of deceased persons and images of places that could cause sorrow.

-

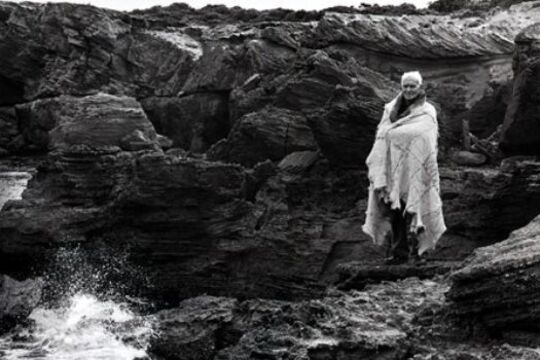

Possum Skin Cloaks

... River and the other little creeks that run into Reddy Lake. You've got Reddy One, Two and Three which are about 7km out of Kerang on the Swan Hill Road. Between the lakes, the tribes came and they sat. The men would sit around one side of the lake ...CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

Continuing the practice of making and wearing possum skin cloaks has strengthened cultural identity and spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities across Victoria.Embodying 5,000 years of tradition, cultural knowledge and ritual, wearing a possum skin cloak can be an emotional experience. Standing on the barren escarpment of Thunder Point with a Djargurd Wurrong cloak around his shoulders, Elder Ivan Couzens felt an enormous sense of pride in what it means to be Aboriginal.

In this story, eight Victorian Elders are pictured on Country and at home in cloaks that they either made or wore at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony.

In a series of videos, the Elders talk about the significance of the cloaks in their lives, explain the meanings of some of the designs and motifs, and reflect on how the cloaks reinforce cultural identity and empower upcoming generations.

Uncle Ivan’s daughter, Vicki Couzens, worked with Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm and Maree Clarke on the cloak project for the Games. In the essay, Vicki describes the importance of cloaks for spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities and in ceremony in mainstream society.

Traditionally, cloaks were made in South-eastern Australia (from northern NSW down to Tasmania and across to the southern areas of South Australia and West Australia), where there was a cool climate and abundance of possums. From the 1820s, when Indigenous people started living on missions, they were no longer able to hunt and were given blankets for warmth. The blankets, however, did not provide the same level of waterproof protection as the cloaks.

Due to the fragility of the cloaks, and because Aboriginal people were often buried with them, there are few original cloaks remaining. A Gunditjmara cloak from Lake Condah and a Yorta Yorta cloak from Maiden's Punt, Echuca, are held in Museum Victoria's collection. Reproductions of these cloaks are held at the National Museum of Australia.

A number of international institutions also hold original cloaks, including: the Smithsonian Institute (Washington DC), the Museum of Ethnology (Berlin), the British Museum (London) and the Luigi Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography (Rome).

Cloak-making workshops are held across Victoria, NSW and South Australia to facilitate spiritual healing and the continuation of this traditional practice.

-

Sound in Space

... One of Melbourne most impressive neo-gothic spaces, the enormous sandstone church of St Monica in Mount Alexander Road, Moonee Ponds, provided a host of spatial possibilities for voices moving through the building in changing configurations ...Music always interacts with the architecture in which it is heard.

Melbourne has some wonderful acoustic environments. Often, these spaces were built for other purposes – for example the splendid public and ecclesiastical buildings from the first 100 years of the city’s history, and more recent industrial constructions.

Exploiting ‘non-customized’ spaces for musical performance celebrates and explores our architectural heritage.

For 30 years, the concerts of Astra Chamber Music Society have ranged around Melbourne’s architectural environment. Each concert has had a site-specific design that takes advantage of the marvellous visual qualities, spatial possibilities, and acoustic personality of each building.

The music, in turn, contributes a new quality to the perception of the buildings, now experienced by audiences as a sounding space - an area where cultural issues from music’s history are traversed, and new ideas in Australian composition are explored.

In this story take a tour of some of Melbourne’s intimate, hidden spaces and listen to the music that has filled their walls.

For further information about Astra Chamber Music Society click here.

-

Lucinda Horrocks

Lucinda HorrocksThe Missing

... the Australians were sent to the Western Front of France and Belgium, where from 1916 to1918 tens of thousands of Australian soldiers died. Campaigns such as Fromelles, Somme 1, Ypres/Passchendaele and Menin Road would become notorious for the number of Australian ...When WW1 brought Australians face to face with mass death, a Red Cross Information Bureau and post-war graves workers laboured to help families grieve for the missing.

The unprecedented death toll of the First World War generated a burden of grief. Particularly disturbing was the vast number of dead who were “missing” - their bodies never found.

This film and series of photo essays explores two unsung humanitarian responses to the crisis of the missing of World War 1 – the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau and the post-war work of the Australian Graves Detachment and Graves Services. It tells of a remarkable group of men and women, ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, who laboured to provide comfort and connection to grieving families in distant Australia.