Showing 37 items

matching high%20country, themes: 'a diverse state','aboriginal culture','family histories','immigrants and emigrants','service and sacrifice','sporting life'

-

Koorie Heritage Trust / NGV Australia / State Library Victoria

Koorie Heritage Trust / NGV Australia / State Library VictoriaKoorie Art and Artefacts

... Deberer (bogong moth) travel hundreds of kilometres from their winter homes to the high country on my country where, in the past we feasted on them in the warmer months. The long zigzag lines represent the wind currents that deberer fly ...Koorie makers of art and artefacts draw upon rich and ancient cultural traditions. There are 38 Aboriginal Language Groups in Victoria, each with unique traditions and stories. These unique traditions include the use of geometric line or free flowing curving lines in designs.

This selection of artworks and objects has been chosen from artworks made across the range of pre-contact, mission era and contemporary times and reflects the richness and diverse voices of Koorie Communities. It showcases prehistoric stone tools, works by 19th century artists William Barak and Tommy McRae right through to artworks made in the last few years by leading and emerging Aboriginal artists in Victoria.

The majority of the items here have been selected from the extensive and significant collections at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne. The Trust’s collections are unique as they concentrate solely on the Aboriginal culture of south-eastern Australia (primarily Victoria). Over 100,000 items are held in trust for current and future generations of Koorie people and provide a tangible link, connecting Community to the past.

Within the vibrant Koorie Community, artists choose their own ways of expressing identity, cultural knowledge and inspiration. In a number of short films Uncle Wally Cooper, Aunty Linda Turner and Aunty Connie Hart practice a range of traditional techniques and skills. These short documentaries show the strength of Koorie culture today and the connection with past traditions experienced by contemporary Koorie artists.

Taungurung artist Mick Harding draws upon knowledge from his Country about deberer, the bogong moth: "The long zigzag lines represent the wind currents that deberer fly on and the gentle wavy lines inside deberer demonstrate their ability to use those winds to fly hundreds of kilometres to our country every year."

Koorie artists today also draw inspiration from the complex and changing society we are all part of. Commenting on his artwork End of Innocence, Wiradjuri/Ngarigo artist Peter Waples-Crowe explains: "I went on a trip to Asia early in the year and as I wandered around Thailand and Hong Kong I started to think about Aboriginality in a global perspective. This series of works are a response to feeling overwhelmed by globalisation, consumerism and celebrity."

Koorie culture is strong, alive and continues to grow.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

-

Lucinda Horrocks

Lucinda HorrocksThe Missing

... the Australian engagements at Gallipoli: 1686 wounded in the Dardenelles, reported in the Age newspaper on the 15 May 1915. The numbers of wounded and dead from Gallipoli were a dreadful shock. No one then had any idea how high the number of dead would reach once ...When WW1 brought Australians face to face with mass death, a Red Cross Information Bureau and post-war graves workers laboured to help families grieve for the missing.

The unprecedented death toll of the First World War generated a burden of grief. Particularly disturbing was the vast number of dead who were “missing” - their bodies never found.

This film and series of photo essays explores two unsung humanitarian responses to the crisis of the missing of World War 1 – the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau and the post-war work of the Australian Graves Detachment and Graves Services. It tells of a remarkable group of men and women, ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, who laboured to provide comfort and connection to grieving families in distant Australia.

-

Language, A Key to Survival: Cantonese-English Phrasebooks in Australia

... Maa Louey (1835-1915) and his family Maa Louey (Ma Lui in Mandarin) was born in 1835 in Canton, China. He is believed to have had a high position in the Imperial Court but to have supported modernisation and social reform. He left China in 1866 ...Most international travellers today are familiar with phrasebooks. These books provide a guide to pronunciation, useful vocabulary, but most importantly lists of useful phrases to help travellers negotiate their way around a country where they don't speak the language.

Anyone who has tried to communicate across the language divide without such a tool knows how valuable they are.

This web story explores how Chinese from the gold rush period onwards have used phrasebooks to help them find their way in Australia. You can compare examples of Cantonese-English phrasebooks from different eras; watch Museum volunteers Nick and David speak English using a gold-rush era phrasebook; learn a little about the lives of some of the people who owned these phrasebooks; and hear Mr Ng and Mr Leong discuss their experiences learning English in Australia and China in the early to mid-twentieth century.

This project is supported through funding from the Australian Government's Your Community Heritage Program.

-

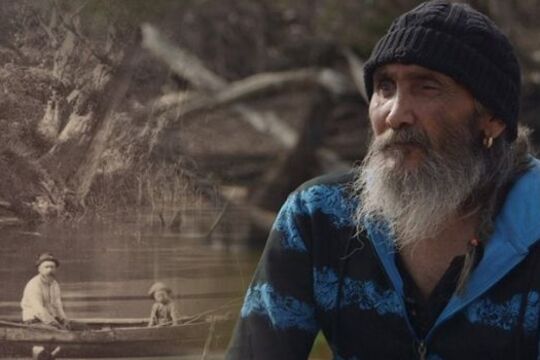

Seeing the Land from an Aboriginal Canoe

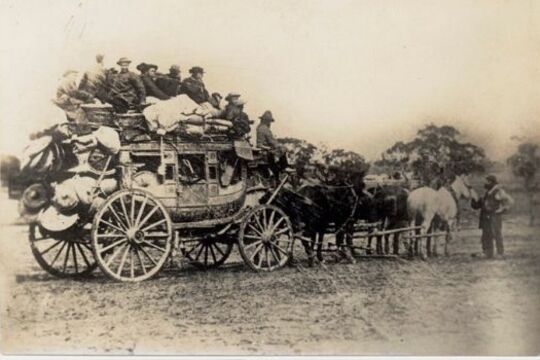

... Flooded Creeks For colonists, the movement of mail, stock and goods was vital. When rivers were low, they could be forded. When rivers flooded and the water level got too high, Aboriginal people would often be employed to ferry goods by canoe ...This project explores the significant contribution Aboriginal people made in colonial times by guiding people and stock across the river systems of Victoria.

Before European colonisation Aboriginal people managed the place we now know as Victoria for millennia. Waterways were a big part of that management. Rivers and waterholes were part of the spiritual landscape, they were valuable sources of food and resources, and rivers were a useful way to travel. Skills such as swimming, fishing, canoe building and navigation were an important aspect of Aboriginal Victorian life.

European explorers and colonists arrived in Victoria from the 1830s onwards. The newcomers dispossessed the Aboriginal people of their land, moving swiftly to the best sites which tended to be close to water resources. At times it was a violent dispossession. There was resistance. There were massacres. People were forcibly moved from their traditional lands. This is well known. What is less well known is the ways Aboriginal people helped the newcomers understand and survive in their new environment. And Victoria’s river system was a significant part of that new environment.

To understand this world we need to cast ourselves back into the 19th century to a time before bridges and cars, where rivers were central to transport and movement of goods and people. All people who lived in this landscape needed water, but water was also dangerous. Rivers flooded. You could drown in them. And in that early period many Europeans did not know how to swim. So there was a real dilemma for the newcomers settling in Victoria – how to safely cross the rivers and use the rivers to transport stock and goods.

The newcomers benefited greatly from Aboriginal navigational skills and the Aboriginal bark canoe.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images of deceased persons and images of places that could cause sorrow.

-

Possum Skin Cloaks

... was offered the choicest cuts but he refused them all, only taking the head, which he carried up into the high tree. Then he told the head of Berrimul that in future, emus were not to defend their nests and were to allow the Kulin to help themselves ...CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

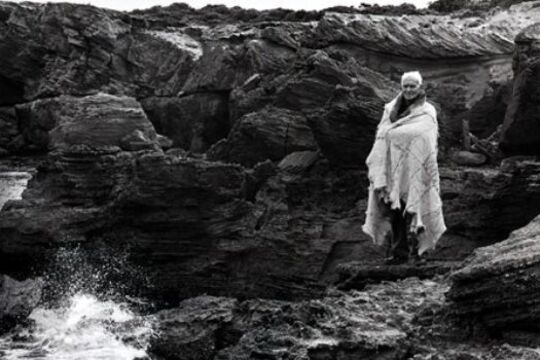

Continuing the practice of making and wearing possum skin cloaks has strengthened cultural identity and spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities across Victoria.Embodying 5,000 years of tradition, cultural knowledge and ritual, wearing a possum skin cloak can be an emotional experience. Standing on the barren escarpment of Thunder Point with a Djargurd Wurrong cloak around his shoulders, Elder Ivan Couzens felt an enormous sense of pride in what it means to be Aboriginal.

In this story, eight Victorian Elders are pictured on Country and at home in cloaks that they either made or wore at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony.

In a series of videos, the Elders talk about the significance of the cloaks in their lives, explain the meanings of some of the designs and motifs, and reflect on how the cloaks reinforce cultural identity and empower upcoming generations.

Uncle Ivan’s daughter, Vicki Couzens, worked with Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm and Maree Clarke on the cloak project for the Games. In the essay, Vicki describes the importance of cloaks for spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities and in ceremony in mainstream society.

Traditionally, cloaks were made in South-eastern Australia (from northern NSW down to Tasmania and across to the southern areas of South Australia and West Australia), where there was a cool climate and abundance of possums. From the 1820s, when Indigenous people started living on missions, they were no longer able to hunt and were given blankets for warmth. The blankets, however, did not provide the same level of waterproof protection as the cloaks.

Due to the fragility of the cloaks, and because Aboriginal people were often buried with them, there are few original cloaks remaining. A Gunditjmara cloak from Lake Condah and a Yorta Yorta cloak from Maiden's Punt, Echuca, are held in Museum Victoria's collection. Reproductions of these cloaks are held at the National Museum of Australia.

A number of international institutions also hold original cloaks, including: the Smithsonian Institute (Washington DC), the Museum of Ethnology (Berlin), the British Museum (London) and the Luigi Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography (Rome).

Cloak-making workshops are held across Victoria, NSW and South Australia to facilitate spiritual healing and the continuation of this traditional practice.