Showing 5 items matching "Veterans"

-

World War One: Coming Home

... veterans ...From 1920 until 1993, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre operated first as Bundoora Convalescence Farm and then as Bundoora Repatriation Hospital.

For more than seventy years, it was home to hundreds of returned servicemen. These men were not only physically damaged by their wartime experiences, their mental health was also dramatically affected. Despite the severe trauma, sometimes it took years or decades for the conditions to emerge.

For some servicemen, this meant being unable to sleep, hold down a job, maintain successful relationships or stay in one place, whilst others experienced a range of debilitating symptoms including delusions and psychosis. While these men tried to cope as best they could, they were rarely encouraged to talk openly about what they had seen or done. The experience of war haunted their lives and the lives of their families as they attempted to resume civilian life.

At this time, there was little understanding around trauma and mental health. For some returned servicemen and their families, it was important that their mental illness was acknowledged as being a consequence of their war service. This was not only due to social stigma associated with mental illness generally, but also because war pensions provided families with greater financial security.

This is as much the story of the Bundoora Repatriation Hospital as it is the story of a mother and daughter uncovering the history of the man who was their father and grandfather respectively. That man was Wilfred Collinson, who was just 19 when he enlisted in the AIF. He fought in Gallipoli and on the Western Front, saw out the duration of the war and returned home in 1919. He gained employment with the Victorian Railways and met and married Carline Aminde. The couple went on to have four children. By 1937, Wilfred Collinson’s mental state had deteriorated and he would go on to spend the remainder of his life – more than 35 years – as a patient at Bundoora.

We know so little about the lives and stories of men like Wilfred, the people who cared for them, the people who loved them and the people they left behind. For the most part the voices of the men themselves are missing from their own narrative and we can only interpret their experiences through the words of authorities and their loved ones.

-

Geelong Voices

... complete thanks to funding that has been provided at various times over the past seven years by: The Friends of the Geelong Heritage Centre, The Geelong Family History Group, The Local History Grants Program - Vic. Govt., The Department of Veteran Affairs ...Stories of World War 1, World War 2 and the Vietnam War as told by Geelong residents.

During World War 1 and World War 2 Geelong residents - whether joining the Armed Forces as soldiers, nurses, pilots, or helping out at home on projects such as the Australian Women’s Land Army - were swept up in the action. Motivated by youthful enthusiasm, the desire for adventure, and intense feelings of patriotism, they joined in hordes. For many, however, the war was not what they expected.

The Geelong Voices Oral History Project was established in 2001. The project collected recordings of diverse programs broadcast by a range of groups - including multicultural groups, women’s groups, trade unions, Aboriginal groups, youth groups and Senior Citizen’s groups - on 3YYR, Geelong Community Radio from 1988 to 2000.

Keeping in Touch and Koori Hour were two such programs. Keeping In Touch was a nostalgic program hosted by Gwlad McLachlan. Gwlad conducted interviews delving into historical aspects of Geelong and Geelong West, including world scale events such as WW1 and WW2, that shaped both the city and its people.

Koori Hour was a Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative Radio Program hosted by a range of people including Richard Fry and Gwenda Black, and consisted of talk about community activities, messages to friends and family, music and discussions about current events. One such event was the launch of “Forgotten Heroes” a book about the overlooked contribution of Aboriginal people to the Australian Armed Forces.

Over 200 of these interviews were recorded off the radio by Gwlad’s neighbour and her husband, Colin. Many of these recordings have been preserved and are available to listen to in digital format at the State Library of Victoria and the Geelong Heritage Centre.

-

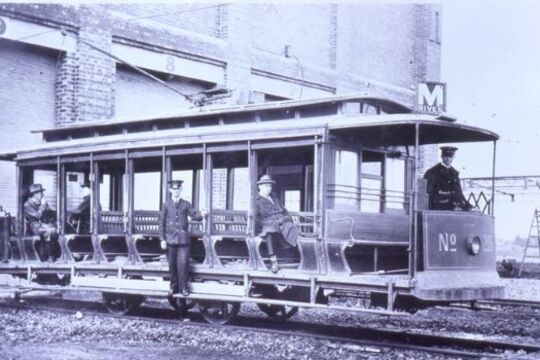

Melbourne Trams: Step aboard!

... a wide range of tasks critical to keeping the system running, including driving, track maintenance, tram maintenance, time tabling, customer service and more. But just as designs of ‘rolling stock’ have changed - from the beloved veteran W class trams ...'Introduction to Melbourne Trams: Step aboard!'

Written by Carla Pascoe, May 2012

Trams are what make Melbourne distinctive as a city. For interstate and overseas visitors, one of the experiences considered compulsory is to ride a tram. When Melbourne is presented to the rest of the world, the tram is often the icon used. The flying tram was one of the most unforgettable moments of the Opening Ceremony of the 2006 Commonwealth Games. When Queen Elizabeth II visited Australia in 2011, she was trundled with regal dignity along St Kilda Road in her very own ‘royal tram’.

The history of trams is closely bound up with the history of this southerly metropolis. Melbourne’s tram system originated during the 1880s economic boom when the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company opened the first cable line. Cable tram routes soon criss-crossed much of the growing city and cable engine houses can still be seen in some inner suburbs, such as the grand building on the south-east corner of Gertrude and Nicholson streets, Fitzroy. Some older passengers like Daphne Rooms still remember riding cable cars.

In the late 19th century, cable and electric tram technologies were vying for supremacy. Australia’s first electric tram line opened in 1889, running through what was then farmland from Box Hill station to Doncaster. The only surviving clue that a tram line once traversed this eastern suburb is the eponymous Tram Road, which follows the former tram route in Doncaster.

Gradually, various local councils joined together to create municipal Tramways Trusts, constructing electric lines that extended the reach of the cable system. In 1920 the tram system came under centralised control when the Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board (MMTB) consolidated the routes and began electrifying all cable lines.

Manpower shortages during World War II meant that Australian women stepped into many roles previously reserved for men. The tramways were no exception, with women being recruited as tram conductors for the first time. After the war, tram systems were slowly shut down in cities around both Australia and the world, as transport policies favoured the motor vehicle. But thanks to the stubborn resistance of MMTB Chairman, Sir Robert Risson, as well as the wide, flat streets that characterise the city’s geography, Melbourne retained its trams.

Melbourne’s tram industry has always possessed a unique workplace culture, characterised by fierce camaraderie and pride in the role of the ‘trammie’ (the nickname for a tram worker). Many Trammies, like Bruce MacKenzie, recall that they joined the tramways because a government job was seen as a job for life. But the reason they often remain for decades in the job is because of the strong bonds within the trammie ‘family’. This is partly due to the many social events and sporting clubs that have been attended by Trammies, as Bruce MacKenzie remembers. It is also because the demands of shift work bond people together, explains Roberto D’Andrea.

The tram industry once employed mainly working-class, Anglo-Australian men. After World War II, many returned servicemen joined the ranks, bringing a military-style discipline with them. With waves of post-war migration the industry became more ethnically diverse, as Lou Di Gregorio recalls. Initially receiving Italian and Greek workers from the 1950s and 1960s, from the 1970s the tramways welcomed an even broader range of Trammies, from Vietnamese, South American, Turkish and other backgrounds.

Trammies perform a wide range of tasks critical to keeping the system running, including driving, track maintenance, tram maintenance, time tabling, customer service and more. But just as designs of ‘rolling stock’ have changed - from the beloved veteran W class trams to the modern trams with their low floors, climate control and greater capacity - so too have the jobs of Trammies changed over time. Bruce MacKenzie remembers joining the Preston Workshops in the 1950s when all of Melbourne’s fleet was constructed by hand in this giant tram factory. Roberto D’Andrea fondly recalls the way that flamboyant conductors of the 1980s and 1990s would perform to a tram-load of passengers and get them talking together. As a passenger, Daphne Rooms remembers gratefully the helping role that the connies would play by offering a steadying arm or a piece of travel advice.

Trams have moved Melburnians around their metropolis for decades. As Daphne maintains, ‘If you can’t get there by tram, it’s not worth going’. Everyone has memories of their experiences travelling on trams: some funny, some heart-warming and some frustrating. Tram driver, Lenny Bates, tells the poignant story of the blind boy who would sometimes board his tram on Collins Street and unhesitatingly call out the names of the streets they passed. As the films in this collection demonstrate, every passenger has their routes that they customarily ride and these routes take on a personal meaning to their regulars. You could say that every tram line has its own distinct personality. Whilst the way the tram system is run inevitably changes across time, one thing has been constant: trams have always played a central role in the theatre of everyday life in Melbourne.

-

Lucinda Horrocks

Lucinda HorrocksThe Missing

... the Armistice was announced. Veteran volunteers included the Indigenous war veteran Edward Smith and Frank Cahir MM DSM, who was at the Gallipoli landing and then the Western Front. The AGD worked in the fields at Pozières and Villers-Bretonneux, which had ...When WW1 brought Australians face to face with mass death, a Red Cross Information Bureau and post-war graves workers laboured to help families grieve for the missing.

The unprecedented death toll of the First World War generated a burden of grief. Particularly disturbing was the vast number of dead who were “missing” - their bodies never found.

This film and series of photo essays explores two unsung humanitarian responses to the crisis of the missing of World War 1 – the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau and the post-war work of the Australian Graves Detachment and Graves Services. It tells of a remarkable group of men and women, ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, who laboured to provide comfort and connection to grieving families in distant Australia.

-

The Ross Sea Party

... James Paton (1869-1917) on the ice just prior to Aurora leaving the Antarctic after the relief of the stores party. Paton was an Antarctic veteran. He was on the crew of Morning when it relieved Scott’s party in 1902, on the Nimrod transporting ...As Shackleton’s ambitious 'Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition' of 1914 foundered, the Ross Sea party, responsible for laying down crucial supplies, continued unaware, making epic sledging journeys across Antarctica, to lay stores for an expedition that would never arrive.

In 1914 Ernest Shackleton advertised for men to join the Ross Sea Party which would lay supply deposits for his 'Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition'. Three Victorians were selected for the ten-man shore party: Andrew Keith Jack (a physicist), Richard Walter Richards (a physics teacher from Bendigo), and Irvine Owen Gaze (a friend of Jack’s).

The Ross Sea party commenced laying supplies in 1915 unaware that Shackleton’s boat Endurance had been frozen in ice and subsequently torn apart on the opposite side of the continent (leading to Shackleton’s remarkable crossing of South Georgia in order to save his men). Thinking that Shackleton’s life depended on them, the Ross Sea Party continued their treacherous work, with three of the men perishing in the process. The seven survivors (including Jack, Richards and Gaze) were eventually rescued in 1917 by Shackleton and John King Davis.

In total, the party’s sledging journeys encompassed 169 days, greater than any journey by Shackleton, Robert Scott, or Roald Amundsen – an extraordinary achievement.

Jack, Gaze and others in the party took striking photographs during their stay. Jack later compiled the hand coloured glass lantern slides, which along with his diaries, are housed at the State Library of Victoria.