Showing 4 items matching "bark canoe"

-

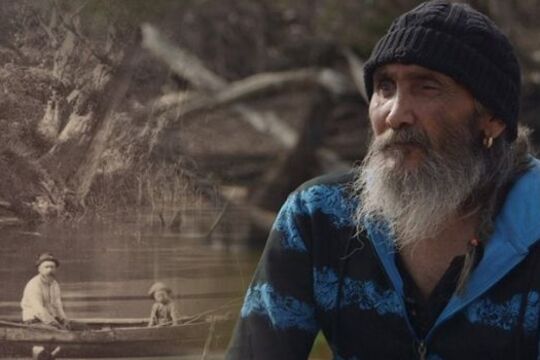

Seeing the Land from an Aboriginal Canoe

... Photograph: F. Kruger, 'Natives and Bark Canoe', c. 1870... Aboriginal bark canoes were made and what they were used for in the swamps and waterways of Dja Dja Wurrung language country. He talks about the impacts of colonisation and the gold rush on the landscape on the lives of Dja Dja Wurrung people. Lucinda.... So there was a real dilemma for the newcomers settling in Victoria – how to safely cross the rivers and use the rivers to transport stock and goods. The newcomers benefited greatly from Aboriginal navigational skills and the Aboriginal bark canoe ...This project explores the significant contribution Aboriginal people made in colonial times by guiding people and stock across the river systems of Victoria.

Before European colonisation Aboriginal people managed the place we now know as Victoria for millennia. Waterways were a big part of that management. Rivers and waterholes were part of the spiritual landscape, they were valuable sources of food and resources, and rivers were a useful way to travel. Skills such as swimming, fishing, canoe building and navigation were an important aspect of Aboriginal Victorian life.

European explorers and colonists arrived in Victoria from the 1830s onwards. The newcomers dispossessed the Aboriginal people of their land, moving swiftly to the best sites which tended to be close to water resources. At times it was a violent dispossession. There was resistance. There were massacres. People were forcibly moved from their traditional lands. This is well known. What is less well known is the ways Aboriginal people helped the newcomers understand and survive in their new environment. And Victoria’s river system was a significant part of that new environment.

To understand this world we need to cast ourselves back into the 19th century to a time before bridges and cars, where rivers were central to transport and movement of goods and people. All people who lived in this landscape needed water, but water was also dangerous. Rivers flooded. You could drown in them. And in that early period many Europeans did not know how to swim. So there was a real dilemma for the newcomers settling in Victoria – how to safely cross the rivers and use the rivers to transport stock and goods.

The newcomers benefited greatly from Aboriginal navigational skills and the Aboriginal bark canoe.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images of deceased persons and images of places that could cause sorrow.

-

Megan Cardamone

Megan CardamoneGanagan

... bark canoe ...I dreamt about weaving a net. So I did just that. I wove a net! When I started weaving my net my mind wandered back in time and I thought about how it must have been for my ancestors who lived along the mighty Murray River.

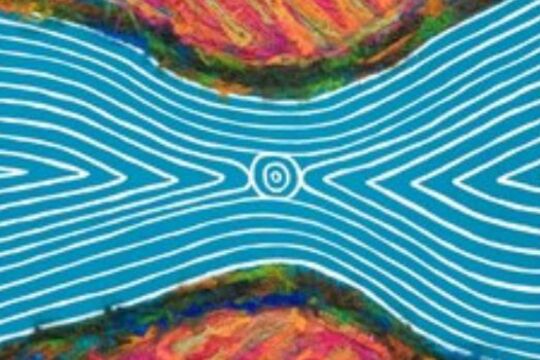

GLENDA NICHOLLS Waddi Waddi/Yorta Yorta/Ngarrinjeri

Glenda Nicholls entered her Ochre Net into the Victorian Indigenous Art Awards in 2012 and was the winner of the Koorie Heritage Trust Acquisition Award.

When Glenda’s Ochre Net came into the Trust’s care, it inspired this exhibition of artworks and stories relating to waterways and their significance to Koorie people. Powerful spiritual connections to waterways, lakes and the sea are central to Koorie life and culture.

The works shown in Ganagan Deep Water come from the Trust’s collections and represent many Koorie cultural groups from south-eastern Australia.

The Ganagan Deep Water exhibition at the Koorie Heritage Trust was sponsored by Melbourne Water.

This online component of the Ganagan exhibition is sponsored by the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme, supported by the Australian Government through the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Ganagan means ‘deep water’ in the Taungurung language.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users of this website are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons and places that could cause sorrow.

-

Koorie Heritage Trust / NGV Australia / State Library Victoria

Koorie Heritage Trust / NGV Australia / State Library VictoriaKoorie Art and Artefacts

... Uncle Wally Cooper, Yorta Yorta Elder, shows us how to make a bark canoe. ...Koorie makers of art and artefacts draw upon rich and ancient cultural traditions. There are 38 Aboriginal Language Groups in Victoria, each with unique traditions and stories. These unique traditions include the use of geometric line or free flowing curving lines in designs.

This selection of artworks and objects has been chosen from artworks made across the range of pre-contact, mission era and contemporary times and reflects the richness and diverse voices of Koorie Communities. It showcases prehistoric stone tools, works by 19th century artists William Barak and Tommy McRae right through to artworks made in the last few years by leading and emerging Aboriginal artists in Victoria.

The majority of the items here have been selected from the extensive and significant collections at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne. The Trust’s collections are unique as they concentrate solely on the Aboriginal culture of south-eastern Australia (primarily Victoria). Over 100,000 items are held in trust for current and future generations of Koorie people and provide a tangible link, connecting Community to the past.

Within the vibrant Koorie Community, artists choose their own ways of expressing identity, cultural knowledge and inspiration. In a number of short films Uncle Wally Cooper, Aunty Linda Turner and Aunty Connie Hart practice a range of traditional techniques and skills. These short documentaries show the strength of Koorie culture today and the connection with past traditions experienced by contemporary Koorie artists.

Taungurung artist Mick Harding draws upon knowledge from his Country about deberer, the bogong moth: "The long zigzag lines represent the wind currents that deberer fly on and the gentle wavy lines inside deberer demonstrate their ability to use those winds to fly hundreds of kilometres to our country every year."

Koorie artists today also draw inspiration from the complex and changing society we are all part of. Commenting on his artwork End of Innocence, Wiradjuri/Ngarigo artist Peter Waples-Crowe explains: "I went on a trip to Asia early in the year and as I wandered around Thailand and Hong Kong I started to think about Aboriginality in a global perspective. This series of works are a response to feeling overwhelmed by globalisation, consumerism and celebrity."

Koorie culture is strong, alive and continues to grow.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

-

Nyernila - Listen Continuously: Aboriginal Creation Stories of Victoria

... and continued his journey to Port Albert; he was alone carrying a bark canoe on his head. As he was walking he heard a constant tapping sound but, look as he may, he could not find the source of it. At last he reached the deep waters of the inlet and put his ...This story is based on the unique publication Nyernila – Listen Continuously: Aboriginal Creation Stories of Victoria.

The uniqueness is differentiated by two significant and distinguishing features. It is the first contemporary compilation of Victorian Aboriginal Creation Stories told by Victorian Aboriginal People, and it is the first to extensively use languages of origin to tell the stories.

‘Nyernila’ to listen continuously – a Wergaia/Wotjobaluk word recorded in the 20th century. To listen continuously. What is meant by this term. What meaning is being attempted to be communicated by the speaker to the recorder? What is implied in this term? What is the recorder trying to translate and communicate to the reader?

‘Nyernila’ means something along the lines of what is described in Miriam Rose Ungemerrs ‘dadirri’ – deep and respectful listening in quiet contemplation of Country and Old People. This is how our Old People, Elders and the Ancestors teach us and we invite the reader to take this with them as they journey into the spirit of Aboriginal Victoria through the reading of these stories.

Our stories are our Law. They are important learning and teaching for our People. They do not sit in isolation in a single telling. They are accompanied by song, dance and visual communications; in sand drawings, ceremonial objects and body adornment, rituals and performance. Our stories have come from ‘wanggatung waliyt’ – long, long ago – and remain ever-present through into the future.

You can browse the book online by clicking the items below, or you can download a PDF of the publication here.

nyernila

nye

ny like the ‘n’ in new

e like the ‘e’ in bed

rn

a special kind of ‘n’

i

i like the ‘i’ in pig

la

la