Showing 11 items matching "indigenous art"

-

Megan Cardamone

Megan CardamoneGanagan

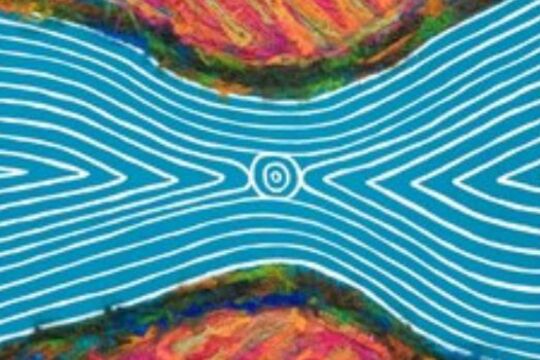

... Indigenous art... Waddi/Yorta Yorta/Ngarrinjeri Glenda Nicholls entered her Ochre Net into the Victorian Indigenous Art Awards in 2012 and was the winner of the Koorie Heritage Trust Acquisition Award. When Glenda’s Ochre Net came into the Trust’s care, it inspired ...I dreamt about weaving a net. So I did just that. I wove a net! When I started weaving my net my mind wandered back in time and I thought about how it must have been for my ancestors who lived along the mighty Murray River.

GLENDA NICHOLLS Waddi Waddi/Yorta Yorta/Ngarrinjeri

Glenda Nicholls entered her Ochre Net into the Victorian Indigenous Art Awards in 2012 and was the winner of the Koorie Heritage Trust Acquisition Award.

When Glenda’s Ochre Net came into the Trust’s care, it inspired this exhibition of artworks and stories relating to waterways and their significance to Koorie people. Powerful spiritual connections to waterways, lakes and the sea are central to Koorie life and culture.

The works shown in Ganagan Deep Water come from the Trust’s collections and represent many Koorie cultural groups from south-eastern Australia.

The Ganagan Deep Water exhibition at the Koorie Heritage Trust was sponsored by Melbourne Water.

This online component of the Ganagan exhibition is sponsored by the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme, supported by the Australian Government through the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Ganagan means ‘deep water’ in the Taungurung language.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users of this website are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons and places that could cause sorrow.

-

Badger Bates

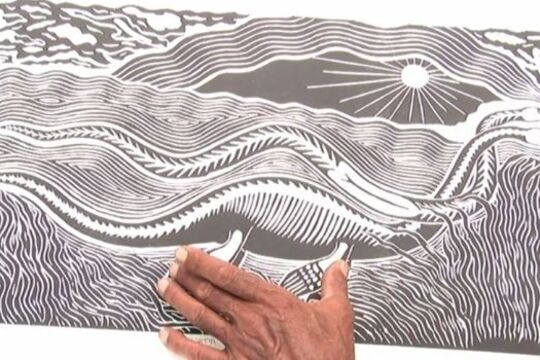

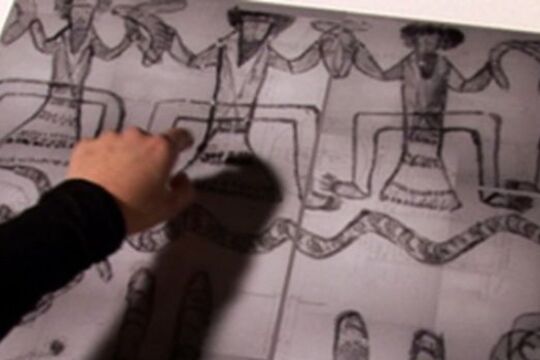

... indigenous art ...Badger Bates (William Brian Bates) was raised by his extended family and his grandmother Granny Moysey, with whom he travelled the country, learning about the language, history and culture of the Paakantji people of the Darling River, or Paaka.

When he was about 8 years old Granny Moysey started to teach him to carve emu eggs and make wooden artefacts in the traditional style, carving by ‘feeling through his fingers.’

Badger works in linoprint, wood, emu egg and stone carving, and metalwork, reflecting the motifs, landforms, animals, plants and stories of Paakantji land. His art is an extension of a living oral tradition, and in his work we find the wavy and geometric lines from the region’s wooden artefacts; places of ceremonial and mythological importance; depictions of traditional life such as hunting and gathering bush tucker; and stories about the ancestral spirits; as well as contemporary issues such as the degradation of his beloved Darling River.

-

Lorraine Northey Connelly

... indigenous art ...Once a symbol of cultural survival, traditional crafts have in recent years become a means of reaffirming cultural identity.

In the hands of Waradgerie artist Lorraine Northey Connelly, this rich tradition undergoes further reinterpretation. She transforms woven string baskets and coolamons into contemporary colonial artefacts, using rustic materials, synthetic paint, ochre painted on sheets of corrugated iron, scrap metals and wire netting: expressive of a shared history and her own heritage of mixed cultures.

Over the past fourteen years Lorraine has been re-discovering her childhood environments, namely the mallee and riverine, acquiring a knowledge of local native and introduced plants and their cultural uses. Lorraine's personal interest in the protection of the environment and equality for all is represented in her art, through the use of recycled materials and symbols of reconciliation.

-

What’s Going On!

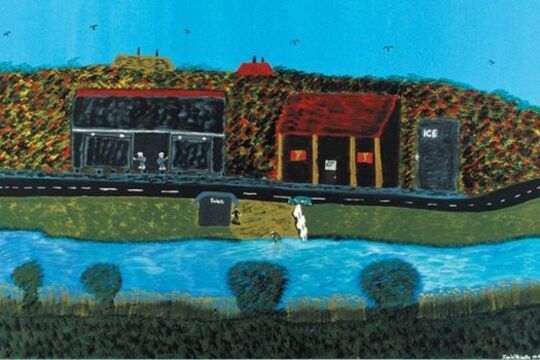

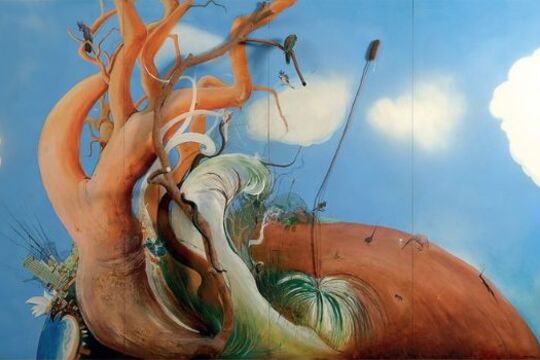

... indigenous art ...What’s Going On! was a groundbreaking exhibition presenting contemporary indigenous artists from the Murray Darling basin.

Taking Mildura as the centre, at the confluence of the Murray and Darling Rivers, the exhibition ranges from Menindee, Wilcannia and Broken Hill to the north and north east, Berri in the south west and Swan Hill to the east, dissolving State boundaries that fragment this distinct region. Uniting the artists in the exhibition are extended family networks and connections to country.

There is a much-loved story told by Aboriginal people on the Murray, that when you open out the swim bladder of a Murray cod, the tree-like forms of its skin reveal the place where the fish was born. Aboriginal children are sometimes told that this is the very same tree under which they were born. These various skin stories reveal the connection of people to the Murray Darling river system, where ‘everyone has a place under the tree’.

-

Contemporary Artists Honour Barak

... Indigenous art ...During the 1860s, at the time of the NGV’s founding, William Barak (1863–1903) was a Wurundjeri leader and artist of great renown, working for his people at Coranderrk, near Healesville. In honour of the NGV’s 150th anniversary, the Felton Bequest commissioned three contemporary artists to create installations that honour Barak’s art and life.

Vernon Ah Kee’s Ideas of Barak, consists of three parts in different media. Jonathan Jones’s untitled (muyan) is an installation of five light boxes that pulse with LED geometric designs. Brook Andrew’s Marks and witness is a dizzying wall drawing of Wiradjuri designs of zigzag and diamond that reference Barak’s possum skin cloak designs.

These works are on display in the multimedia room of the Indigenous Galleries, above the escalator and in the stairwell of The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia at Federation Square.

In this story, Vernon Ah Kee and Jonathan Jones talk about their creative process and Auntie Joy Murphy-Wandin talks about Barak, and the artists’ engagement with him, and about Barak’s work at Coranderrk.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users of this website are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons and places that could cause sorrow.

-

Panorama: A question of perspective

... indigenous art ...TarraWarra Museum of Art is located in the picturesque Yarra Valley in Victoria, Australia.Visitors to the Museum are afforded a spectacular, resonant and panoramic experience of ‘nature’ through the north facing windows. The view stretches towards the distant Toolangi rainforest across planted vines, native bushland and farmland.

The region is surrounded by a spectacular mountain range that includes Mt Baw Baw, Mt Donna Buang, Mt Juliet, Mt Riddell and Mt Toolebewong. As these names attest, we are situated in an area of significant Indigenous history and colonisation. Tarrawarra is a Wurundjeri word that translates approximately as ‘slow moving water’ and is the name given to the area in which the Museum is located.

The Yarra Valley sunsets, soundscapes, seasonal changes, Indigenous histories, ecological vulnerabilities and environmental challenges are in a complex and ever changing entanglement. Since 2012, the Museum has explored this context through special exhibitions and commissions, forums and performances, screenings and lectures. As such, the Museum has sought to understand the complexity of our site, and with that, the broader intersections between art and landscape. Artists provide us the opportunity to ‘see’ the landscape in a different way. They imagine it, call it into being, reflect upon it, animate it, unravel its hidden histories, and expose its ecological sensitivities.

Panorama, the exhibition, was an integral part of this ongoing conversation and imaginative exploration. Our intention was not so much to write a narrative history of Australian landscape painting. Rather, it was to be attuned to the intermingling of voices, points of view, perspectives - colonial and modern, contemporary and Indigenous – that comprise the uniquely Australian persistence to unravel the ‘patter’ of nature.

As a phenomenon to which we are all very accustomed, it is easy to overlook the simple fact that for a landscape to come into being it requires a ‘point of view’, a subjective consciousness to frame a particular expanse of the natural world. As the art historian Simon Schama remarks in his landmark survey on the genre, Landscape and Memory, ‘it is our shaping perception that makes the difference between raw matter and landscape’. [i] The centrality of the viewer’s position in constructing a vista is clearly evident in terms such as ‘perspective’, ‘prospect’, and ‘view point’ which are synonymous with ‘position’, ‘expectation’, and ‘stance’. This highlights that there is always an ineluctable ideological dimension to the landscape, one that is intimately entwined with a wide range of social, economic, cultural and spiritual outlooks. Turning to the notion of the panorama, a brief survey of its conception and infiltration into everyday speech, reveals how our way of seeing the landscape is often tantamount to the formation and delineation of our personal, communal, and national identities.

The term panorama was first coined to describe the eponymous device invented by the British painter Robert Barker which became a popular diversion for scores of Londoners in the late 18th century. Consisting of a purpose built rotunda-like structure on whose cylindrical surface landscape paintings or historical scenes were displayed, ‘The Panorama’ contained a central platform upon which viewers observed the illusionistic spectacle of a sweeping 360 degree vista. With its ambitious, encyclopaedic impulse to capture and concentrate an entire panoply of elements into a singular view, it is telling that this construction would soon give rise to an adjective to describe, not only an expansive view extending in all directions, but also a complete and comprehensive survey of a subject. As the curators Jean-Roch Bouiller and Laurence Madeline argue, these different meanings convey ‘the very essence of the panoramic phenomenon: the central role of perspective, a certain appropriation of the world that follows, the feeling of dominating a situation simply due to having a wide and complete view’.[ii] Indeed, as art historian Michael Newman reveals, the whole notion of the panorama originated in military conceptions of the landscape as a battlefield, whereby strategic vantage points are key to tactical planning.[iii] Underlying its transformation into a form of popular entertainment, the panorama is rooted in a particular form of political authority based on surveying, mapping and commanding the subject of the view.

In this exhibition, the term panorama was invoked to acknowledge that ways of perceiving the landscape have their own histories which have arisen out of particular social, political and cultural contexts. As the landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn contends: ‘In every landscape are ongoing dialogues; there is “no blank slate”; the task is to join the conversation’.[iv]However, far from claiming to present an unbroken view or a complete survey, Panorama challenged the very notion of a single, comprehensive monologue by presenting a series of works which engaged with the discourse of landscape in a diverse range of voices. Taking advantage of the tremendous depth and strength of the TarraWarra Museum of Art collection gifted by its founders Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC, the exhibition was staged in two parts, with a different selection of paintings exhibited in each half. Displayed in distinct groupings which explored alternative themes and concerns, Panorama highlighted the works of key artists who have redefined, expanded and interrogated the idea of the landscape in ways which suggest that it is far from settled.

Further Information

[i] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, New York: Vintage Books, 1996, p. 10.

[ii] Jean-Roch Bouiller and Laurence Madeline, Introductory text for the exhibition I Love Panoramas, MuCEM and the Musées d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva, 4 November 2015 - 29 February 2016, URL: http://www.mucem.org/en/node/4022

[iii] See ‘The Art Seminar’ in Landscape Theory, (eds. Rachael Ziady DeLue and James Elkins), New York and London: Routledge, 2008, p. 130.

[iv] Anne Whiston Spirn, ‘“One with Nature”: Landscape, Language, Empathy and Imagination’ in Landscape Theory, 2008, p. 45.

-

The Koorie Heritage Trust Collections and History

... Indigenous art ...CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

The Koorie Heritage Trust was established in 1985 with a commitment to protect, preserve and promote the living culture of the Indigenous people of south-east Australia.

Today the Trust boasts extensive collections of artefacts, paintings, photographs, oral history recordings and library materials.

Further information on Tommy McRae can be found at the State Library of Victoria's Ergo site

-

Vicki Couzens

Vicki CouzensMeerreeng-an Here Is My Country

... Indigenous art ...The following story presents a selection of works from the book Meerreeng-an Here is My Country: The Story of Aboriginal Victoria Told Through Art

Meerreeng-an Here is My Country: The Story of Aboriginal Victoria Told Through Art tells the story of the Aboriginal people of Victoria through our artworks and our voices.

Our story has no beginning and no end. Meerreeng-an Here is My Country follows a cultural, circular story cycle with themes flowing from one to the other, reflecting our belief in all things being connected and related.

Our voices tell our story. Artists describe their own artworks, and stories and quotes from Elders and other community members provide cultural and historical context. In these ways Meerreeng-an Here Is My Country is cultural both in its content and in the way our story is told.

The past policies and practices of European colonisers created an historic veil of invisibility for Aboriginal communities and culture in Victoria, yet our culture and our spirit live on. Meerreeng-an Here Is My Country lifts this veil, revealing our living cultural knowledge and practices and strengthening our identity.

The story cycle of Meerreeng-an Here Is My Country is presented in nine themes.

We enter the story cycle by focusing on the core cultural concepts of Creation, Country, culture, knowledge and family in the themes 'Here Is My Country' and 'Laws for Living'.

The cycle continues through ceremony, music, dance, cloaks, clothing and jewellery in 'Remember Those Ceremonies' and 'Wrap Culture Around You'. Land management, foods, fishing, hunting, weapons and tools follow in 'The Earth is Kind' and 'A Strong Arm and A Good Eye'.

Invasion, conflict and resilience are explored in 'Our Hearts Are Breaking'. The last two themes, 'Our Past Is Our Strength' and 'My Spirit Belongs Here', complete the cycle, reconnecting and returning the reader to the entry point by focusing on culture, identity, Country and kin.

Visit the Koorie Heritage Trust website for more information on Meerreeng-an Here Is My Country

-

Possum Skin Cloaks

... Indigenous art ...CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

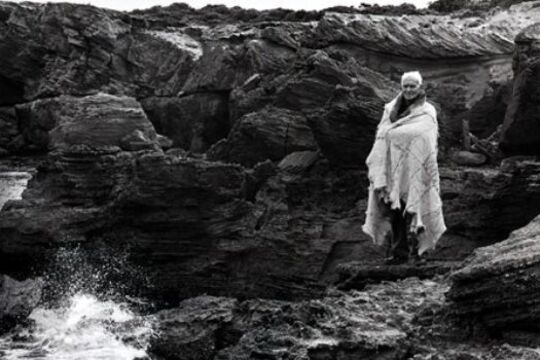

Continuing the practice of making and wearing possum skin cloaks has strengthened cultural identity and spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities across Victoria.Embodying 5,000 years of tradition, cultural knowledge and ritual, wearing a possum skin cloak can be an emotional experience. Standing on the barren escarpment of Thunder Point with a Djargurd Wurrong cloak around his shoulders, Elder Ivan Couzens felt an enormous sense of pride in what it means to be Aboriginal.

In this story, eight Victorian Elders are pictured on Country and at home in cloaks that they either made or wore at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony.

In a series of videos, the Elders talk about the significance of the cloaks in their lives, explain the meanings of some of the designs and motifs, and reflect on how the cloaks reinforce cultural identity and empower upcoming generations.

Uncle Ivan’s daughter, Vicki Couzens, worked with Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm and Maree Clarke on the cloak project for the Games. In the essay, Vicki describes the importance of cloaks for spiritual healing in Aboriginal communities and in ceremony in mainstream society.

Traditionally, cloaks were made in South-eastern Australia (from northern NSW down to Tasmania and across to the southern areas of South Australia and West Australia), where there was a cool climate and abundance of possums. From the 1820s, when Indigenous people started living on missions, they were no longer able to hunt and were given blankets for warmth. The blankets, however, did not provide the same level of waterproof protection as the cloaks.

Due to the fragility of the cloaks, and because Aboriginal people were often buried with them, there are few original cloaks remaining. A Gunditjmara cloak from Lake Condah and a Yorta Yorta cloak from Maiden's Punt, Echuca, are held in Museum Victoria's collection. Reproductions of these cloaks are held at the National Museum of Australia.

A number of international institutions also hold original cloaks, including: the Smithsonian Institute (Washington DC), the Museum of Ethnology (Berlin), the British Museum (London) and the Luigi Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography (Rome).

Cloak-making workshops are held across Victoria, NSW and South Australia to facilitate spiritual healing and the continuation of this traditional practice.

-

Women's Suffrage

... . Bindi Cole is an emerging artist and photographer. In 2007 she won the Victorian Indigenous Art Photography Award and was also a finalist in the National Photographic Portrait Prize (National Portrait, Canberra). ...2008 marked the centenary of the right for Victorian non-indigenous women to vote.

During 2008 the achievements of the tenacious indigenous and non-indigenous women who forged a path through history were celebrated through an array of commemorative activities.

How the right to vote was won…

In 1891 Victorian women took to the streets, knocking door to door, in cities, towns and across the countryside in the fight for the vote.

They gathered 30,000 signatures on a petition, which was made of pages glued to sewn swathes of calico. The completed petition measured 260m long, and came to be known as the Monster Petition. The Monster Petition is a remarkable document currently housed at the Public Records Office of Victoria.

The Monster Petition was met with continuing opposition from Parliament, which rejected a total of 19 bills from 1889. Victoria had to wait another 17 years until 1908 when the Adult Suffrage Bill was passed which allowed non-indigenous Victorian women to vote.

Universal suffrage for Indigenous men and women in Australia was achieved 57 years later, in 1965.

This story gives an overview of the Women’s Suffrage movement in Victoria including key participants Vida Goldstein and Miles Franklin, and the 1891 Monster Petition. It documents commemorative activities such as the creation of the Great Petition Sculpture by artists Susan Hewitt and Penelope Lee, work by artists Bindi Cole, Louise Bufardeci, and Fern Smith, and community activities involving Kavisha Mazzella, the Dallas Neighbourhood House, the Victorian Women Vote 1908 – 2008 banner project, and much more…

Further information can be found at the State Library of Victoria's Ergo site Women's Rights

Learn more about the petition and search for your family members on the Original Monster Petition site at the Parliament of Victoria.

Educational Resources can be found on the State Library of Victoria's 'Suffragettes in the Media' site.

-

William Barak

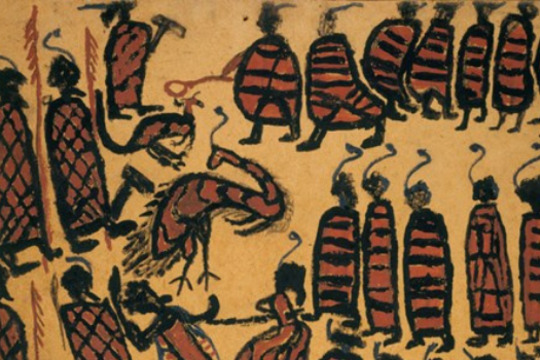

... Judith Ryan, senior curator of Indigenous Art in the National Gallery of Victoria, discusses the life and work of William Barak. ...Diplomat, artist, story-teller and leader, Wurundjeri (Woiwurung) man William Barak worked all his life to protect the rights and culture of his people, and to bridge the gap between settlers and the land’s original custodians.

Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police as his father had been, before becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve - a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville.

Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artifacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations.

CULTURAL WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander users are warned that this material may contain images and voices of deceased persons, and images of places that could cause sorrow.

Further information on William Barak can be found at the State Library of Victoria's Ergo site.