Showing 11 items with the theme 'Gold Rush'

-

Mapping Great Change

This series of films and stories is centred on a beautiful and complex map with the ungainly name: Plan of the General Survey from the Town of Malmsbury to the Porcupine Inn, from the sources of Forest Creek to Golden Point, shewing the Alexandrian Range, also Sawpit Gully, Bendigo and Bullock Creeks.

In many ways, the map is a mirror of our times: the map is a record of the 'critical years' between 1835 and 1852 in which the dispossession of Aboriginal people of Victoria was allowed to occur; we contemporary people are in the "critical decade" for making the changes necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change.

If we fail to act effectively in this decade, it will be as loaded with moral and practical consequences for coming generations as the moral and policy failures of our colonial ancestors was for the Traditional Owners of the land.

-

Lola Montez, Star Attraction

When gold fever gripped central Victoria in the 1850s, hundreds of thousands of people arrived from all over the world, including Africa, the Americas, China, Europe and India.

The tent cities that appeared overnight brought people together regardless of whether they were rich or poor, aristocrat or convict, man or woman, lucky or unlucky. Everyone co-existed side by side, creating a society in a state of flux. With roles less fixed, it was a relatively liberal time.

But by 1856 the teeming, transgressive society began to settle. Ballarat was becoming an established town where men were comfortable to bring their wives and families. The process of social stratification, and the rise of associated moral agendas, began to take hold.

It was into this atmosphere that international sensation, Lola Montez, arrived.

Montez was born Maria Eliza Dolores Rosanna Gilbert in Ireland in 1818. Self-made, creative and charismatic, she mixed with notable figures of her day, including George Sand and Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. She was politically influential, and the consort to King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who made her Countess of Landsfeld. Her other lovers included composer Franz Liszt and writer Alexandre Dumas.

Montez was hugely popular and controversial, just as pop star, Madonna, was a century later. Crowds descended on the Victoria Theatre in the Goldfields to witness her notorious 'Spider Dance', a titillating version of a tarantella.

Through Montez and her 'Spider Dance' (as represented by the interpretive theatre presented at the Sovereign Hill Outdoor Museum), this story explores the broader social forces at play on the goldfields at the time she visited.

The story also includes several moving postcards, giving snapshots of life on the goldfields in the nineteenth century.

-

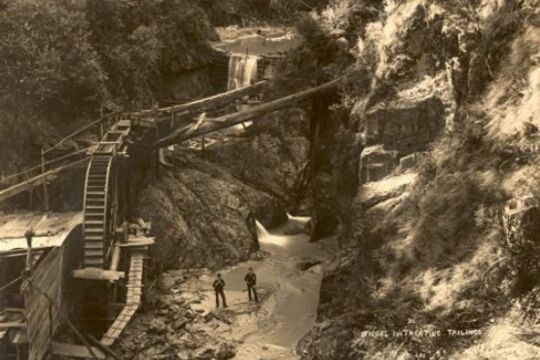

Walhalla: fires, floods and tons of gold

In a remote, steep, and heavily timbered valley in the Victorian Alps, in the summer of 1862-63, a small party of prospectors found encouraging signs of gold at the fork of a tributary of the Thomson River. It was December. By February of the next year an immense quartz reef had been discovered.

This reef – Cohen’s Reef - yielded over 50 tonnes of gold, making Walhalla one of Victoria’s richest and most vibrant towns, and home to thousands: with hotels, shops, breweries, churches, school, jail and its own newspaper. It also had its own photographic studio, headed by the Lee brothers.

Several albums still survive of Walhalla at its peak, providing a fascinating, evocative photographic record of a 19th century mining town; capturing a moment that was to be shortlived.

In 1910 the railway arrived, but too late: the gold was disappearing. The town emptied out and began its long sleep, until the 1980s when restorations began in earnest, and electricity finally arrived in 1998.

William Joseph Bessell (ex Councillor of the Shire of Walhalla) was presented this series of photos in 1909 on the eve of his departure from Walhalla.

-

Ballarat Underground

The story of Ballarat is tied to the story of mining, with hundreds of thousands of people flocking there in the 1850s to seek their fortune. The few lucky ones became wealthy, but most were faced with the harsh reality of needing a regular income. The Ballarat School of Mines was established in 1870 to train men in all aspects of mining.

When the First World War was declared in 1914, thousands of Ballarat men enlisted. Many of these men were miners who had trained at the Ballarat School of Mines and worked in the town’s mining industries. Their skills were recognised, and tunnelling companies were created to utilise them in strategic and secretive ways. Underground (literally) campaigns were designed where the men tunnelled underneath enemy lines to lay explosives. The intention: to cause significant destruction from below. It was dangerous and cramped work, not for the faint hearted.

One hundred years on, local collecting organisation Victorian Interpretive Projects, in conjunction with Ballarat Ranges Military Museum, is asking local residents and relatives of former Ballarat miners to share their photographs, objects and stories.

This is the story of the miners who left Ballarat to fight in the First World War. It is also the story of the people seeking to commemorate them through research and family history, enabling an ongoing legacy through contributions to the public record.

-

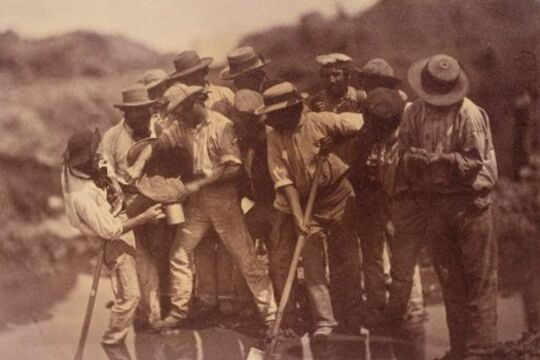

Early Photographs - Gold

These images are part of the first photographic series of Australian scenes presented for sale to the public. Produced by the studio of Antoine Fauchery and Richard Daintree in 1858, these photograph are from a series of 53 collectively known as the Fauchery-Daintree Album.

Using the latest collodion wet-plate process, Fauchery and Daintree produced their collection of albumen silver prints at a time when the sales of photographs were flourishing.

Antoine Fauchery and Richard Daintree produced iconic images of both early gold diggers and the landscapes scarred by the exploding search for gold, which attracted miners from all over the world and created the boom that made Melbourne the fastest growing metropolis of the time.

Antoine Fauchery and Richard Daintree were both migrants who tried their luck on the goldfields – Daintree coming out from England in 1853, Fauchery from France in 1852.

Unsuccessful on the goldfields, in 1857 they combined forces to produce a series of photographs titled Sun Pictures of Victoria, capturing important early images of the goldfields, Melbourne Streets, landscapes and portraits of Indigenous Victorians. Using the new collodion wet-plate process, they created albumen silver prints of a rare quality for the time.

Further information on Antoine Fauchery's time in Melbourne can be found at the State Library of Victoria's Ergo site.

-

Language, A Key to Survival: Cantonese-English Phrasebooks in Australia

Most international travellers today are familiar with phrasebooks. These books provide a guide to pronunciation, useful vocabulary, but most importantly lists of useful phrases to help travellers negotiate their way around a country where they don't speak the language.

Anyone who has tried to communicate across the language divide without such a tool knows how valuable they are.

This web story explores how Chinese from the gold rush period onwards have used phrasebooks to help them find their way in Australia. You can compare examples of Cantonese-English phrasebooks from different eras; watch Museum volunteers Nick and David speak English using a gold-rush era phrasebook; learn a little about the lives of some of the people who owned these phrasebooks; and hear Mr Ng and Mr Leong discuss their experiences learning English in Australia and China in the early to mid-twentieth century.

This project is supported through funding from the Australian Government's Your Community Heritage Program.

-

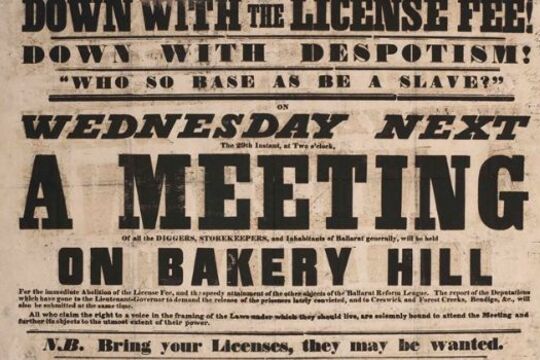

Eureka Stories

What is Eureka and what happened there?

In the early hours of 3 December 1854 a force of police and other troops charged a reinforced camp constructed by miners on the Eureka gold diggings. About 150 diggers were inside the stockade at the time of the attack. In the fighting, 4 soldiers and about 30 other people were killed, and another 120 people taken prisoner. Thirteen people from the stockade were charged with treason – these men were either tried and found not guilty, or charges against them were dropped.

Many people think of the Eureka Stockade as a battle between the diggers (rebellious Irish fighting for democracy) and the police and colonial militia (the forces of the British Crown in the Colony). It’s nice to have a single story to make sense of everything. Eureka, however, is not a single simple narrative. Several stories intertwine and involve many of the same people and places. Let’s look at some of them.

The Hated Gold Licences

In 1854, people mining for gold around Victoria had to pay a monthly fee of 30 shillings for the right to mine, regardless of how much gold they found. Someone who had been looking for gold unsuccessfully for months still had to pay the same fee as someone who was pulling out gold by the pound. Diggers argued that it was an unfair tax, imposed on them without their consent, as they did not have the right to vote. (After the Goldfields Royal Commission the licensing fee was changed to a tax on gold when it was being exported.)

Not only did the diggers resent the licence fee, they were angry at the way the goldfields police went about checking that miners had licences. Diggers claimed that police were beating people up or chaining them to trees if they could not produce a licence, and undertaking unnecessary inspections on people they didn’t like. Resentment of the licence fee and the conduct of police in their “licence hunts” was expressed across the Victorian goldfields.

The Unfair Treatment of Diggers by the Police and Justice System

People around the Victorian goldfields were also unhappy with the lack of thoroughness with which police had investigated a number of goldfields crimes. They were concerned about what they thought was the unfair and secretive way people were charged and convicted of crimes. There were claims by people living on the goldfields that it was necessary to bribe police and government officials in order to do business and stay safe. As the goldfields populations increased, tensions between the goldfields communities and police and other government officials rose.

In Ballarat a series of events (a murder, an arrest and a hotel burning) in late 1854 involving police and Ballarat locals led to the arrests of three men for burning down the Eureka Hotel. These arrests caused enormous disquiet in the area, adding weight to calls by the Ballarat Reform League and other organisations around the goldfields for a fundamental change to the system of government in the Colony – the next element in our Eureka story.

Demands for a Democratic Political System

Since the early 1850s people had been calling for the government to abandon the gold licensing system, remove the gold commissioners, and provide the Colony with a better policing and justice system. Despite an investigation by the Victorian parliament into the goldfields in 1853 (a Legislative Council Select Committee) the government did not make significant changes. By November 1854 an organisation called the Ballarat Reform League had formed in response to official inaction and had written a Charter of democratic rights. They organised a "monster meeting" in Ballarat on 11 November 1854, to have it accepted, and met with Governor Hotham on 27 November 1854, to demand his acceptance of the Charter, and the release of the three prisoners charged with burning down the Eureka Hotel.

Population Explosion

The people calling for these changes to taxes, justice and political participation came from many different parts of the world, such as the United States, Canada, England, Ireland, Scotland, Italy, Germany. This corner of South-Eastern Australia was rapidly changing as thousands and thousands of people arrived to search for gold. Many of these people were educated and from middle-class or merchant backgrounds. The domination of squatters running sheep on large land holdings was being challenged by dense populations of people in goldrush regions generating enormous wealth in the colony, and a desire from these recent arrivals to take up land, and have a say in the making of laws.

We have looked at some parts of the Eureka story; at what unfolded around the colony as a result of this mix of people, events and system of government. There are many other stories about Eureka. To find out more, you can explore the stories through original documents at Eureka on Trial.

-

Goldfields Stories: Dai gum san, big gold mountain

It may come as a surprise to some that the oldest Imperial Dragon in the world, Loong, is to be found in Bendigo, Victoria.

In 1851 gold was found in the Bendigo region. News reached China and by 1853 Chinese miners started to arrive at Dai Gum San (Big Gold Mountain). By 1855 there were up to 4000 Chinese in the Bendigo goldfields, about one fifth of the population.

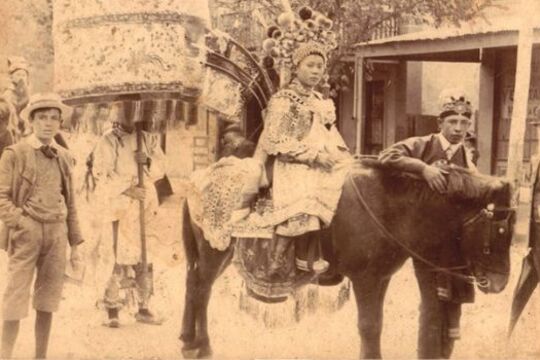

By the 1860s, Bendigo was becoming a wealthy and established town, and in 1869 The Bendigo Easter Fair and Procession was initiated to raise funds for the Bendigo Benevolent Asylum and Hospital. By 1871, the Chinese, keen to support the wider community, joined the procession, providing music, theatre and acrobatic displays. Their position as the main attraction at the Fair was confirmed by 1879.

All of the costumes, flags and musical instruments were imported from China, with no expense spared. For the 1882 Fair, 100 cases of processional regalia were imported. In 1892 a further 200 cases arrived, along with Loong, the Imperial five-clawed dragon, who made his first appearance that year.

The traditions established in the 1860s by the Bendigo Chinese community continue to this day. As well as providing the main attraction in the Bendigo Easter Festival, ceremonies such as the Awakening of the Dragon are conducted. These traditions reflect uniquely preserved traditions, many of which were lost or discontinued in mainland China. They also reflect traditions, such as the main celebration taking place at Easter rather than Chinese New Year, that trace the history of the Chinese in Victoria.

The remarkable collection of 19th Century processional regalia that has been preserved by the Chinese community in Bendigo is held in the Golden Dragon Museum. It is not only a collection of world significance but, importantly, it contextualises and preserves the living heritage of both Victoria and China.

-

Wind & Sky Productions

Wind & Sky ProductionsMany Roads: Stories of the Chinese on the goldfields

In the 1850s tens of thousands of Chinese people flocked to Victoria, joining people from nations around the world who came here chasing the lure of gold.

Fleeing violence, famine and poverty in their homeland Chinese goldseekers sought fortune for their families in the place they called ‘New Gold Mountain’. Chinese gold miners were discriminated against and often shunned by Europeans. Despite this they carved out lives in this strange new land.

The Chinese took many roads to the goldfields. They left markers, gardens, wells and place names, some which still remain in the landscape today. After a punitive tax was laid on ships to Victoria carrying Chinese passengers, ship captains dropped their passengers off in far away ports, leaving Chinese voyagers to walk the long way hundreds of kilometres overland to the goldfields. After 1857 the sea port of Robe in South Australia became the most popular landing point. It’s estimated 17,000 Chinese, mostly men, predominantly from Southern China, walked to Victoria from Robe following over 400kms of tracks.

At the peak migration point of the late 1850s the Chinese made up one in five of the male population in fabled gold mining towns of Victoria such as Ballarat, Bendigo, Castlemaine, Beechworth and Ararat. It was not just miners who took the perilous journey. Doctors, gardeners, artisans and business people voyaged here and contributed to Victoria’s economy, health and cultural life. As the nineteenth century wore on and successful miners and entrepreneurs returned home, the Chinese Victorian population dwindled. However some chose to settle here and Chinese culture, family life, ceremony and work ethic became a distinctive feature of many regional Victorian towns well into the twentieth century.

By the later twentieth century many of the Chinese relics, landscapes and legacy of the goldrush era were hidden or forgotten. Today we are beginning to unearth and celebrate the extent of the Chinese influence in the making of Victoria, which reaches farther back than many have realised.

-

Chinese Australian Families

Dreams of Jade and Gold: Chinese families in Australia's history

From the 1840s onwards, Chinese people have come to Australia inspired by dreams of happiness, longevity and prosperity - of 'jade and gold' in a new and strange land. For most of that time, Chinese people in Australia have been predominantly male. Most of them were temporary sojourners who came to earn money for their families back in the village - most did not intend to settle in Australia.

Despite the predominance of male sojourning, a small proportion of Chinese men in nineteenth-century Australia brought their wives and children to live with them, or married here. As Australian-born children of these families grew to adulthood, their parents would seek brides and grooms on their behalf amongst other Chinese families in Australia.

The majority of post-1905 Chinese brides of Chinese-Australian sons were never able to settle here. Some children were born in China or Hong Kong. Some were born in Australia. Families like this were split for decades, until immigration laws were relaxed.

In the nineteenth century, many of the Chinese men who wanted wives in Australia married or lived de facto with non-Chinese women. At least 500 European-Chinese partnerships are estimated to have occurred before 1900.

Despite repeated waves of racism and official discrimination from the 1840s to the 1970s, a sizeable number of families of Chinese background have put down roots in this country.

In 1973 the Whitlam government abolished racist provisions in immigration laws. Since then, the number of ethnic Chinese migrants has increased dramatically. They have come primarily as family groups - not as sojourners, but as permanent immigrants. They come not only from China and Hong Kong, but also from Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia, as well as from further afield. The Chinese are now a highly visible and generally accepted part of the Australian community of cultures.

The text above has been abstracted from an essay 'Dreams of Jade and Gold: Chinese families in Australia's history' written by Paul Macgregor for the publication The Australian Family: Images and Essays. The full text of the essay is available as part of this story.

This story is part of The Australian Family project, which involved 20 Victorian museums and galleries. The full series of essays and images are available in The Australian Family: Images and Essays published by Scribe Publications, Melbourne 1998, edited by Anna Epstein. The book comprises specially commissioned and carefully researched essays with accompanying artworks and illustrations from each participating institution.

-

Carissa Goudey

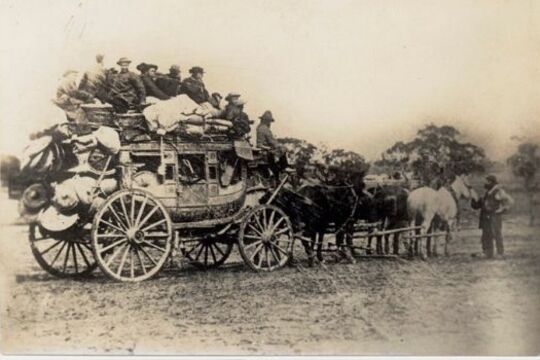

Carissa GoudeyMaking & Using Transport on the Goldfields

During the nineteenth century, horse-drawn vehicles were an essential part of life in rural Victoria.

In Ballarat, local coachbuilding firms assisted with the town’s growth in more ways than providing passage to the diggings. Horse-drawn vehicles were vital for the delivery of goods, responding to emergencies and often symbolised one’s social standing.

The Gold Rush ushered in a period of incredible growth for colonial Victoria. Ballarat’s escalating population and burgeoning industries highlighted the need for horse-drawn transport – not only for getting to the diggings, but also for delivering goods and building material, responding to emergencies and performing significant social rituals.

In the early nineteenth century, the goldfields were dominated by vehicles either imported from England or English-style vehicles built locally. Coaches, carriages and carts were typically constructed part-by-part, one at a time. As a result, each vehicle was highly unique.

By the mid-1850s, the American coachbuilding tradition had arrived on the goldfields. The American method, which had been developing since the 1840s, relied on mass-produced, ready-made components. In comparison to English designs, American coaches were known to be more reliable for goldfields travel; they were primed for long-distance journeys on rough terrain and were less likely to tip over.

As the nineteenth century progressed, a plethora of English, American and European vehicles populated Ballarat – both locally made and imported. The abundance of coaches, carriages and carts – and their value to the Ballarat community – can be seen in photographs and objects catalogued here on Victorian Collections.