Mother Tongue

Mother Tongue

The publication Nyernila – Listen Continuously: Aboriginal Creation Stories of Victoria is unique. This uniqueness is differentiated by two significant and distinguishing features. It is the first contemporary compilation of Victorian Aboriginal Creation Stories told by Victorian Aboriginal People, and it is the first to extensively use languages of origin to tell the stories.

‘Nyernila’ to listen continuously – a Wergaia/Wotjobaluk word recorded in the 20th century. To listen continuously. What is meant by this term. What meaning is being attempted to be communicated by the speaker to the recorder? What is implied in this term? What is the recorder trying to translate and communicate to the reader?

‘Nyernila’ means something along the lines of what is described in Miriam Rose Ungemerrs ‘dadirri’ – deep and respectful listening in quiet contemplation of Country and Old People. This is how our Old People, Elders and the Ancestors teach us and we invite the reader to take this with them as they journey into the spirit of Aboriginal Victoria through the reading of these stories.

Our stories are our Law. They are important learning and teaching for our People. They do not sit in isolation in a single telling. They are accompanied by song, dance and visual communications; in sand drawings, ceremonial objects and body adornment, rituals and performance. Our stories have come from ‘wanggatung waliyt’ – long, long ago – and remain ever-present through into the future.

Aboriginal people are culturally and linguistically diverse Peoples. Our languages come from an oral history tradition stretching back through time immemorial. Across Australia, in pre-European times, there were up to 700 languages being spoken. Through the impacts of invasion and the colonisation of our lands and the cultural genocide practices of the newcomers we were denied our mother tongue. Our Old People fought and died defending our Country. Families were massacred and forced onto missions where our cultural practices were banned. The legacy of this time is still reverberating through our communities.

All Aboriginal people prior to the arrival of the Europeans were multi-lingual, speaking up to or more than five languages. Today 145 are still being spoken with more than half of those endangered. Across Victoria there are about 38 languages or dialects of origin. Many of those languages in Victoria have, in part, been retained within families and local communities. The few fluent speakers remaining belong to one or two languages.

However, despite the impacts of European culture our language has remained embedded within the cultural framework of families and communities. It has survived through our continuing kinship connections, our contemporary language of ‘Aboriginal English’ – a mixture of English, mother tongue words and phrases – and our cultural customs and stories handed down.

Today we are reviving and reawakening our mother tongue languages.

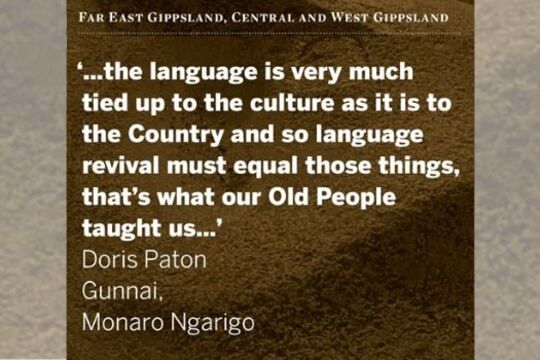

In this process we work with the sounds of our language; the sounds of Country and the knowledge handed down from the Old People. Language is connected to and is the voice of the Country it belongs to, just as we belong to the Country.

We have developed orthographies, sound and spelling systems, so we are able to read and write our language as well as speak it. Through this reclamation and revival process we gather our knowledge through our Elders and community. We re-dream and re-interpret the historical records; those messages left for us by our Old People.

To revive our language we need to make it current and relevant. Much of the vocabulary is from the 19th century and has no words/concepts for current lifestyles. To achieve this we are looking deeply into the meanings of the words, the ways in which our language is constructed and we are learning how our Old People adapted language, made new words and integrated new concepts to accommodate the changing world.

Aboriginal intellectual cultural property has been appropriated into publications and various other mediums since the arrival of Europeans. With this publication we are taking steps to reclaim our stories and languages and retell those stories in our own way, in our voices. It is a re-positioning of our inherent right to own and share our culture; a challenge for readers to consider.

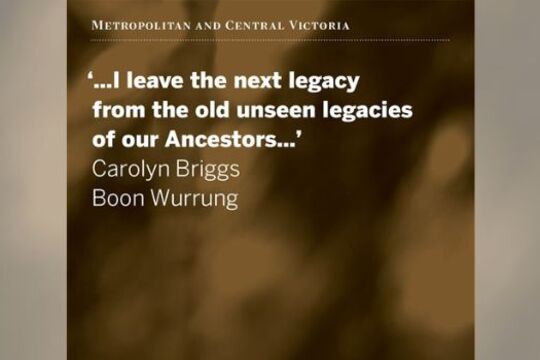

Over the past 20 or more years with VACL leading the way, tireless, impassioned individuals and groups have dedicated themselves to carrying out language revival work across Victoria. VACL and all those who are travelling this collective journey of language revival must be commended and congratulated in bringing this landmark publication to fruition. It is and will remain a legacy for the future.

The stories for this publication were sourced from community, from the knowledge holders, custodians and keepers of those stories. We gathered the stories through community: in workshops specifically directed towards language development and story translation for ‘Nyernila’; from individual and family group contributions; and most importantly through the spirit of generosity our Peoples have in their willingness to share our stories and our Culture.

Story, song, dance, movement, motif/symbol, painting and carving are integral parts of our languages. Our languages are the Voices of the Land. Remember, reclaim, revive and regenerate.

Vicki Couzens, Project Co-ordinator

Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages