The Dreamer and the Cheerful Thing go walking

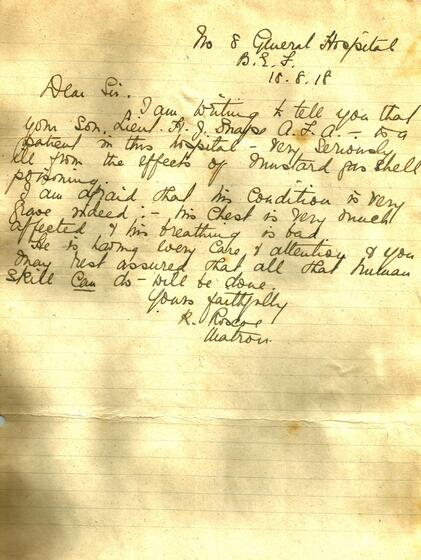

Bob was prone to fits of depression during the war and seems to have been deeply affected by his long enforced absence from home and his loved ones. In a poetic and powerful letter to his father, he describes a dream he had written the day before Harold was gassed.

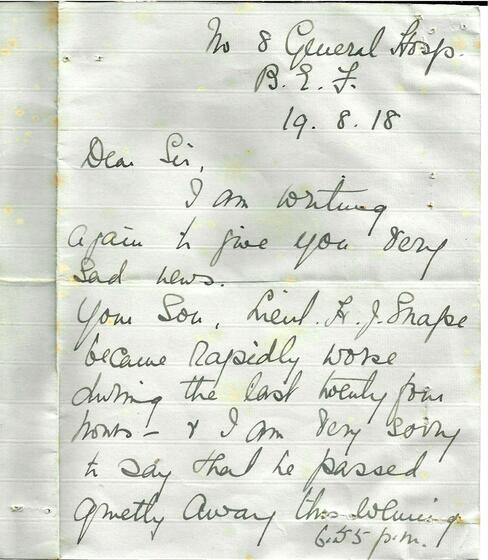

EXCERPT: Bob’s letter to his father, dated 14 August 1918.

The dreamer was meandering through the tired village of - when he bumped into the Cheerful Thing.

“Well?” said the Dreamer.

“Quite well!” said the Cheerful Thing.

Two lorries rumbled past. “Curse the lorries;” muttered the Dreamer, they smother us with mud in the winter, and in the summer they choke us with dust.”

“C’est la guerre!” said the Cheerful Thing, and then added: “Suppose we walk as far as the Canal?”

Arrived at the canal, they sat on the grass on the bank. “I love the smell of the reeds,” remarked the Cheerful Thing. No reply from the Dreamer – he was dreaming of something else, far, far away.

“Nothing doing on the Canal nowadays, what!” continued the Cheerful Thing. “I should have liked to see it in the pre-war days. I can fancy the laden barges gliding slowly past and the horse jogging along the towpath. And look at that lock with the big hole alongside where a bomb has just missed it. Yes, everything seems strangely deserted now: but the water, which has no soul, still keeps flowing, flowing as though nothing has changed. It knows no war. Ignorance is bliss, etc, etc: or one might say: ‘Wars may come and wars may go, but I go on forever’.”

“I wish this war would go; it came quite a long time ago,” said the Dreamer, forcefully, (coming back to earth again with a thud).

The Cheerful Thing gazed carelessly down the Canal. “You don’t see these things in Australia,” he remarked presently.

“Seldom,” answered the Dreamer.

“Rather pretty and peaceful, don’t you think?”

“Yes, but I’d give all their canals for any little Australian creek at present.”

“You don’t say! What creek would the gentleman like?”

“Oh! any old creek. Even the Moonee Ponds, with all its dead pets thrown in.” “I’d like a river for every cat or dog that has finished up in that picturesque and pleasant stream, what?”

“What’s that silly song that goes, ‘I want to get back; I want to get back?’ “ asked the Dreamer, suddenly. “Those confounded words will persist in repeating themselves in my brain.”

“Better see the doctor,” suggested the Cheerful Thing. “Go on sick parade in the morning and get painted with iodine or something,” he added cheerfully.

“Don’t be mad: I’m always like this when I’ve received mail from Home.”

“Trouble is, old man, you think too much.”

“Can’t help it. When the Australian mail comes in, up goes my barometer; but when I’ve finished the last letter, bang goes everything. I fold up the sheets and replace them in the envelopes – then look around me and realise that I am still in France, some 12,000 miles from dear old Home.”

“Dear, oh dear!” said the Cheerful Thing, with a mock sigh. “Well! What’s wrong with France, anyhow? Most delightful place! Delightful climate – er, in summer I mean; and delightful language -- when you happen to see a civilian about, to talk to.”

“Yes, but Australia means Home – and that makes all the difference in the world,” snapped the Dreamer.

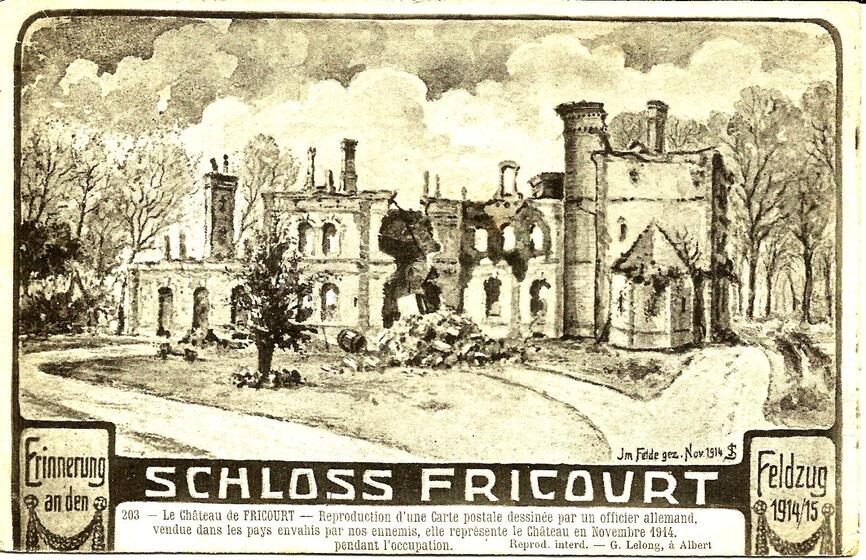

“Mid châteaux and shell-holes tho’ we may roam, Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home,” chanted the Cheerful Thing.“Shut up, can’t you!” cried the Dreamer, “I’m feeling rotten enough now.”

“Well! I guarantee to either kill or cure. I say! After the war, they reckon one will be able to reach Australia in a few days by aerial means.”

“Why, I can reach Australia in a moment, by merely closing my eyes,” said the Dreamer. “I was actually there last night, though I don’t often dream of it nowadays.” I had caught the 20 to 6 from Flinders Street – the same old crawling train. Stopped once on the viaduct and twice between Spencer Street and North Melbourne, and landed me at the old Essendon station about 5 past six. I looked about for my father as I made my exit from the station, but, as he was nowhere to be seen, I concluded he had missed his usual train and would probably be following on the next. I dashed through the twisty old subway and walked briskly down the same old Buckley Street hill, then rushed in the Lorraine Street side gate. Saw my mother standing at the back door and gave her an impulsive kiss. I then had a bit of a wash and slipped into the drawing room for a few minutes on the piano while waiting for father to arrive. My brother Harold was already home, and engaged in printing some photos. Five minutes later, Father and my brother Frank arrived together, and we all sat down to the tea-table in just the same old way. I was just taking my mouthful of soup when something seemed to go wrong and I found myself lying on a board floor, with the first rays of the morning sun trying to struggle through the cracked and dirt-stained glass of our billet’s windows.” The Dreamer finished up with a lump in his throat.

“I was dreaming; I was dreaming! There was sadness in the air,” warbled the Cheerful Thing.

“Jove! It begins to get dusk early now,” interrupted the Dreamer, “I think we’d better return to work again.”

“At night when ‘tis dark and lonely, In dreams it is still with me,” hummed the Cheerful Thing as they rose to go back.