Showing 48 items with themes 'Built Environment' or 'Kelly Country'

-

Rippon Lea Estate

"Do you remember the garden in which you grew up, or the part the backyard played in your family life? Imagine if you had actually grown up in one of Australia's finest gardens.

Created in the English-landscape tradition which traces its roots back to Capability Brown and Humphry Repton, Rippon Lea is one of Australia's most important historic homes, exemplifying the lifestyle of wealthy families living in 19th and 20th century Australian cities. Although its architecture and that of its outbuildings is impressive, it is the mansion’s gardens, which are truly remarkable, both for their landscape qualities and because they have survived many threats and changes in the past 130 years.

Today, the amenities offered by a typical garden are still greatly valued: a safe place for children to play, somewhere to dry the washing, a plot for vegetables and a flower garden that adds colour and produces blooms for the home. Today as then, the scale differs but the experience of owning a garden - with its balance of utility and ornament - is essentially the same.

The National Trust of Australia (Victoria) now runs Rippon Lea as a museum, conserving the architecture and the landscape, and presenting the social history of the owners and their servants. Visitors to Rippon Lea enter a mansion preserved as the Jones family lived in it after their 1938 modernisation. In the pleasure garden the Sargood era is evoked by the staging of a range of performing arts events including opera, theatre, chamber music and outdoor activities."

The text above has been abstracted from an essay Solid Joys and Lasting Treasure: families and gardens written by Richard Heathcote for the publication The Australian Family: Images and Essays. The entire text of the essay is available as part of this story.

This story is part of The Australian Family project, which involved 20 Victorian museums and galleries. The full series of essays and images are available in The Australian Family: Images and Essays published by Scribe Publications, Melbourne 1998, edited by Anna Epstein. The book comprises specially commissioned and carefully researched essays with accompanying artworks and illustrations from each participating institution.

-

Melbourne's Homes

These house plans from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, give us an indication of how those with the means to build larger houses lived.

Servant's quarters, groom's rooms, sculleries, stables, parlours and children's areas give us clues to social attitudes, relationships to children and employees, social mores and living conditions.

-

St Paul's Cathedral

Refusing to set foot in the colony, the eminent Gothic Revivalist architect William Butterfield resorted to sending extremely detailed architectural drawings and plans of St Paul's Cathedral to Australia.

He even produced life-size drawings of columns, window tracery and other features, to ensure the antipodeans could get nothing wrong.

In the end however, he was defeated by distance, and St Paul's was completed by the Australian firm Reed, Henderson and Smart, and later, in the 1930s, the towers he designed (but were not built at the time) were shafted for a new design by Australian architect John Barr.

-

North Shore: Geelong's Boom Town 1920s-1950s

In its heyday of the 1920s - 1950s, North Shore (a small northern suburb of Geelong) was the hub of industrial development in Victoria’s second city.

Situated against the backdrop of Corio Bay, North Shore and its immediate surrounds was home to major industries including Ford, International Harvester, Shell, the Corio Distillery and the Phosphate Cooperative Company of Australia (the 'Phossie').

Residents grew up with these companies literally over the back fence and many of their stories depict childhood memories of mischievous exploration. Many residents were employed by the industries, some hopping from job to job, whilst others spent the majority of their working lives at the likes of Ford or the Phossie.

At the commencement of World War II in September 1939, much of the local industry was placed on war footing. Two thirds of the newly opened International Harvester was commandeered by the R.A.A.F. and an ad hoc airfield was established. The U.S. Air Force arrived shortly thereafter.

The presence of American servicemen has left an enduring impression on the North Shore community. Their arrival was the cause of much local excitement, particularly among the children who made a pretty penny running errands for them. They were also a hit with the ladies, who enjoyed a social dance at the local community hall. The story of the American presence in North Shore remains largely untold, and the reflections of local residents provide a fantastically rare insight into a unique period in Victorian history.

A special thanks to local historians Ferg Hamilton and Bryan Power for their assistance during the making of this story. Also thanks to Gwlad McLachlan for sharing her treasure trove of Geelong stories.

-

Wimmera Stories: Nhill Aeradio Station, Navigating Safely

The Nhill Aeradio Station was a part of a vital national network established in 1938 to provide critical communications and navigation support for an increasing amount of civil aircraft.

Situated at the half-way point of a direct air-route between Adelaide and Melbourne, Nhill was an ideal location for an aeradio station and was one of seventeen such facilities originally built across Australia and New Guinea by Amalgamated Wireless Australasia Ltd (AWA) under contract from the Commonwealth Government.

The Aeradio Station at Nhill operated until 1971, when a new VHF communication network at Mt William in the Grampians rendered it obsolete and the station was decommissioned.

The aeradio building survives today in remarkably original condition, and current work is being undertaken by the Nhill Aviation Heritage Centre group to restore the Aeradio Building and interpret its story as part of a local aviation museum.

-

Erin Wilson

Erin WilsonUrban Fringe

Melbourne is an expanding city, with a growing population and sprawling urban development. It is predicted that by 2056 an additional 4 million people will settle in Greater Melbourne, increasing the population from 5 million to 9 million people over the next 30 years (1). While some expansion is vertical, in the form of high-rise developments, much of this growth is across the peri-urban fringe, described simply as ‘areas on the urban periphery into which cities expand’ (2) or ‘which cities influence’ (3).

In Melbourne, these peri-urban areas of most rapid growth are currently the local government areas of Cardinia, Casey, Hume, Melton, Mitchell, Whittlesea and Wyndham. With population growth comes the inevitable expansion of infrastructure, services and transportation. As the fringes of the city continue to sprawl, what was once the urban fringe and green edge of the city has to be negotiated, as it is increasingly encroached upon.

The artists and photographers in Urban Fringe examine these spaces on the fringe of the expanding city of Melbourne, where urban and natural environments meet, clash and coexist. Beginning with white colonisation and the myth of ‘terra nullius’, these artists discuss the treatment of the Greater Melbourne environment over time, consider the cost of progress, and explore protest and the reclamation of space.

-

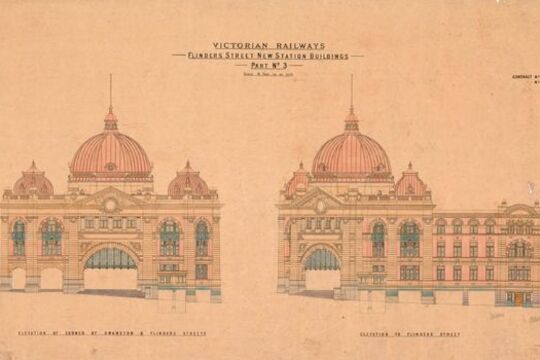

100 Years of Flinders Street Station

Flinders Street Station: icon, meeting place, central to millions of city commuters. The building itself was the result an architectural competition held in 1902, and Mary Lewis, librarian, introduces us to the original winning entry, held at State Library of Victoria.

Explore the changing, and unchanging, face of Melbourne's streetscape with images of Flinders St, from photographs of the late eighteenth century to the works of art that Melbourne's famous railway station has inspired.

In 2010, Flinders Street Station celebrated its 100th birthday.

-

A Station with a Town Attached

"Don't you overlook that Maryborough station, if you take an interest in governmental curiosities. Why, you can put the whole population of Maryborough into it, and give them a sofa apiece, and have room for more." Mark Twain, during his 1895 tour of Australia.

Twain’s remark stuck, and Maryborough became known as the railway station with a town attached.

Why was Maryborough chosen for one of the nation's grandest stations? Was it meant for Maryborough, Queensland? Was it indeed a ‘governmental curiosity’, a monumental bureaucratic mistake?

In fact, neither is the case. The Maryborough Station tells a much larger story: the vision for a rail-connected Victoria in the age that preceded the motor engine. Maryborough would be a crucial junction between the Wimmera, Geelong, Ararat, Warrnambool, Ballarat, Bendigo and Melbourne, especially for freight such as wheat.

The original station was built in 1874 but, as part of the 'Octopus Act' of 1884, Parliamentarians began arguing the case for a grander station.

The new Queen Anne style red brick building with stucco trimmings and Dutch-Anglo influences was erected in 1890-1, with 25 rooms, an ornate clock tower, Flemish gables, oak wall panels, a large portico, and a spectacular platform veranda - the longest in country Victoria.

Here, oral histories, expert opinions and archival photographs from local collections are presented, giving us a sense of the station's importance, its role in an earlier era and, as a magnificent late 19th century Australian building, the place it continues to hold in the district.

-

Wimmera Stories: Murtoa Stick Shed, Enduring Ingenuity

Colloquially known as the Stick Shed, the Marmalake Grain Store Wheat Storage Shed is the largest building in Murtoa, out on the Wimmera plains between Horsham and St Arnaud.

The Stick Shed is a type of grain storage facility built in Victoria during the early 1940s. The Marmalake / Murtoa Grain Store No.1 was built in 1941-42 during a wheat glut, to store wheat that could not be exported during World War II. It is the earliest & last remaining example of this particular grand Australian rural vernacular tradition.

The Stick Shed is 265 metres long, 60.5 metres wide and 19-20 metres high, supported by 560 unmilled mountain ash poles. Its vast gabled interior space and long rows of poles have been likened to the nave of a cathedral.

The Stick Shed demonstrates Australian ingenuity during a time of hardship, it was added to the Victorian Heritage Register in 1990.

Find more stories and photographs about the Stick Shed on the Way Back Then blog.

-

Rural City of Wangaratta / State Library Victoria

Rural City of Wangaratta / State Library VictoriaThe Last Stand of the Kelly Gang: Sites in Glenrowan

Ned Kelly, born in June 1855 at Beveridge, north-east of Melbourne, Northern Victoria, came to public attention as a bushranger in the late 1870s.

He was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol, November 11th, 1880. Kelly is perhaps Australia’s best known folk hero, not least of all because of the iconic armour donned by his gang in what became known as the Siege at Glenrowan (or The Last Stand), the event that led to Ned Kelly’s capture and subsequent execution.

The siege at Glenrowan on Monday, June 28th, 1880, was the result of a plan by the Kelly Gang to derail a Police Special Train carrying Indigenous trackers (the Gang's primary targets), into a deep gully adjacent to the railway line. The plan was put into effect on Saturday, June 26 with the murder [near Beechworth] of Aaron Sherritt, a police informant, the idea being to draw the Police Special Train through the township of Glenrowan, an area the local Kellys knew intimately. After the Glenrowan Affair, the Kelly Gang planned to ride on to Benalla, blow up the undermanned police station and rob some banks.

However, Ned miscalculated, thinking the train would come from Benalla not Melbourne. Instead of the 12 hours he thought it would take for a police contingent to be organized and sent on its way from Benalla, the train took 31 hours to reach Glenrowan. This resulted in a protracted and uncertain wait, leading to the long period of containment of more than 60 hostages in the Ann Jones Inn. It also resulted in a seriously sleep deprived Kelly Gang and allowed for the intervention of Thomas Curnow, a hostage who convinced Ned that he needed to take his sick wife home, enabling him to get away and warn the Police Special train of the danger.

Eventually, in the early morning darkness of Monday, June 28th, the Police Special train slowly pulled into Glenrowan Railway Station, and the police contingent on board disembarked. The siege of the Glenrowan Inn began, terminating with its destruction by fire in the mid afternoon, and the deaths of Joe Byrne, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Earlier, shortly after daylight on the 29th, Ned was captured about 100 metres north east of the Inn.

Glenrowan is situated on the Hume Freeway, 16 kms south of Wangaratta. The siege precinct and Siege Street have State and National Heritage listing. The town centre, bounded by Church, Gladstone, Byrne and Beaconsfield parade, including the Railway Reserve and Ann Jones’ Inn siege site, have State and National listing.

-

Jane Routley and Elizabeth Downes

Jane Routley and Elizabeth DownesFlinders Street Station

The current Flinders Street Station building has been part of the lives of Melbournians for over 100 years.

Inspired by the launch of the latest competition to put forward proposals for its restoration and reinvigoration, and to highlight some of the amazing Flinders Street-related material in Victoria's cultural collections, I will be celebrating the past, present and future of my favorite station.

Over the next few months, I will be recording impressions and stories found whilst exploring the station as it exists today, trawling the internet for related sounds and images (such as this timelapse) and featuring some of the wonderful images of the station that are held in Victoria's cultural collections. As a taster for my future posts, here's a selection of images that I've found.

-

Sound in Space

Music always interacts with the architecture in which it is heard.

Melbourne has some wonderful acoustic environments. Often, these spaces were built for other purposes – for example the splendid public and ecclesiastical buildings from the first 100 years of the city’s history, and more recent industrial constructions.

Exploiting ‘non-customized’ spaces for musical performance celebrates and explores our architectural heritage.

For 30 years, the concerts of Astra Chamber Music Society have ranged around Melbourne’s architectural environment. Each concert has had a site-specific design that takes advantage of the marvellous visual qualities, spatial possibilities, and acoustic personality of each building.

The music, in turn, contributes a new quality to the perception of the buildings, now experienced by audiences as a sounding space - an area where cultural issues from music’s history are traversed, and new ideas in Australian composition are explored.

In this story take a tour of some of Melbourne’s intimate, hidden spaces and listen to the music that has filled their walls.

For further information about Astra Chamber Music Society click here.

-

Kitty Owens

Kitty OwensSummon the Living

Prior to the advent of electronic sound systems, bells were heard ringing throughout the day.

Large bells were attached to buildings. Handheld bells sat on tables and mantel pieces. Bells rang for morning prayer, school time, half time, and dinner time. Bells announced a fire in town or the death of a local. Some bells were passed around within their local community, or re-purposed as presentation gifts, being easily engraved and potentially useful.

This story was originally inspired by Graeme Davison’s book The Unforgiving Minute: How Australia Learned to Tell the Time.

-

Elizabeth Downes

Elizabeth DownesThe Unsuspected Slums

Campaigner Frederick Oswald Barnett recorded the poverty facing many in the Melbourne slums of the 1930s.

“All the houses face back-yards…The woman living in the first house…was so desperately poor that she resolved to save the maternity bonus, and so, with her last baby had neither anaesthetic nor doctor.”

So observed campaigner Frederick Oswald Barnett of the poverty facing many in the Melbourne slums of the 1930s. After touring these slums with Barnett, it’s said the Victorian Premier, Albert Dunstan, couldn’t sleep for days.

In 1936 Dunstan established the Slum Abolition Board, and Barnett became vice-chairman of the newly established Housing Commission of Victoria in 1938.

A Methodist and accountant, Barnett became determined to improve the situation for the poor, sick, elderly and unemployed after encountering a slum in the 1920s. He was an astute crusader who coordinated letter writing campaigns and lectured throughout Victoria using many of his own poignant and arresting photographs of the cramped and unsanitary housing conditions.

-

Paige Gleeson

Paige GleesonMaking Do on ‘the Susso’: The material culture of the Great Depression

There are currently 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic in our oceans. The demands on renewable sources like timber, clean water and soil are so great they are now being used at almost twice the rate that the earth can replenish them. Finite resources like fossil fuel are consumed at an alarming rate, changing the earth’s climate and pushing animal species to the brink of extinction. Current patterns of consumption are exceeding the capacity of the earth’s ability to provide into the future.

All over the world, environmental movements concerned with sustainability have sprung up in response. Conscious consumers are advocating for their right to repair their own electronic devices, fighting a culture of planned obsolesce and disposability. Others are championing the repair, reuse and recycling of clothing and household goods to extend their lives. Reducing waste in the kitchen and promoting food options with lower environmental impact has become increasingly popular.

Climate change may be a uniquely twenty-first century challenge, but sustainability has a history. In 2021 many people are making a conscious choice to embrace anti-consumerism, but during the Great Depression of the 1930s it was necessity that drove a philosophy of mend and make do.

In 1929 stock markets crashed and sent economies around the western world into free fall, triggering the Great Depression. Australia’s economic dependence on wool and wheat exports meant that it was one of the worst affected countries in the world. The impact of the Depression on the everyday lives of Australians was immense. Not everyone was effected with the same severity, but few escaped the poverty and austerity of the years 1929-1933 unscathed.At the height of the Depression in 1932 Australia had an unemployment rate of 29%, and thousands of desperate people around the country queued for the dole. Aboriginal Australians were not eligible for the dole, and had to rely solely on government issued rations.

-

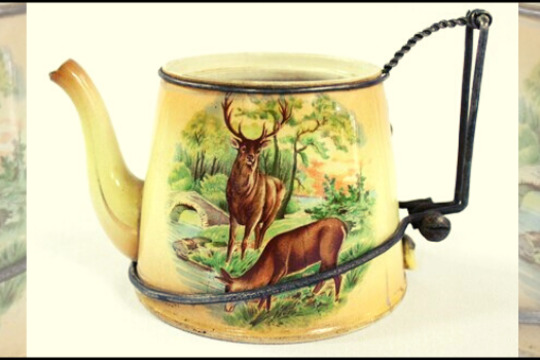

Kitty Owens

Kitty OwensAnother Night

Lighting fades away when a lamp is blown out, or when a switch is clicked off, but the history of lighting has left traces in Victorian cultural collections.

This story looks at items and images relating to the history of lighting in Victoria and considers the various lightscapes created by different types of lighting. This story is inspired by the book Black Kettle and Full Moon by Geoffrey Blainey.

After thousands of years of Aboriginal firelight, European households spent their evenings in dim smoky rooms huddled around a spluttering pool of light. Bright lighting was a luxury. As new energy sources and lighting technology became available nights became brighter, extending the day and changing the night time.