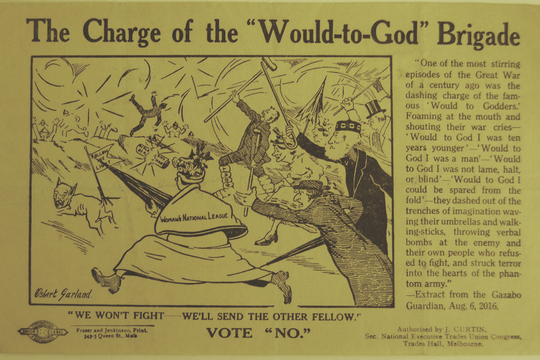

Mannix, like most Australian Catholics, was initially supportive of the British War effort. However, many people’s attitudes shifted after the Easter Rising.

The ‘Easter Rising’ of 1916 was an abortive attempt to overthrow British control of Ireland. In April 1916, a small group of Irish nationalists launched an armed revolt and seized key locations in Dublin. The rising was short lived, and the response by the British government was severe. Court martials were held in secret and executions carried out swiftly. It soon became clear that some of those executed had taken little or no part in the Rising, and evidence also emerged of non-combatants being killed by the British Army without arrest or trial.

At this time, most Australian Catholics had an Irish background. Many had direct family still living in Ireland. As a consequence, they were generally sympathetic to the political problems faced in Ireland, and concerned by the heavy-handed British response, even if they didn’t support the Rising itself.

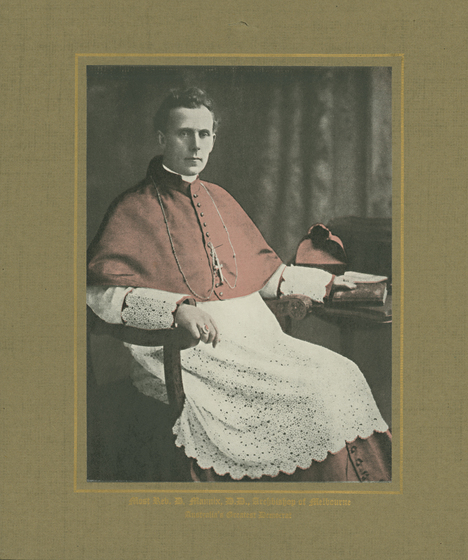

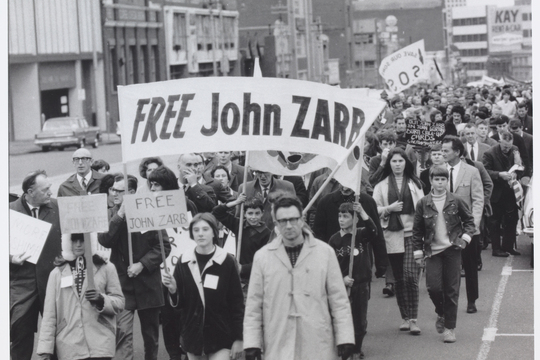

There is no doubt that the incident reduced support for the war, however the response of Catholic Australians to the Easter Rising was complicated. Mannix was considered a moderate on the Irish question, but became the most prominent Catholic opponent to conscription. Archbishop Michael Kelly in Sydney was equivocal on both home rule and conscription while Archbishop Patrick Clune of Perth, too, was a supporter of home rule, but a dedicated conscriptionist. (Clune served as senior Catholic chaplain to the Australian Army.)

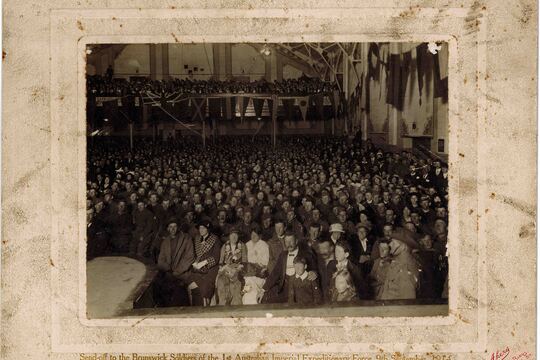

When Mannix spoke out against conscription, he rarely linked the issue to the Irish situation, instead using more familiar arguments relating to sectarianism, workers’ rights and individual liberty. One exception was in a meeting about Irish home rule in Richmond in November 1917, when Mannix alluded to the conscription campaign, and said that he was happy to put Australia first, and “The Empire would have to take second place”.

Further Information:

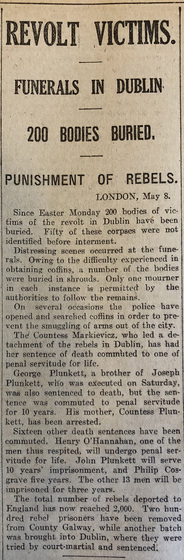

Revolt Victims.

Funerals in Dublin

200 Bodies Buried

Punishment of Rebels.

London May 8.

Since Easter Monday 200 bodies of victims of the revolt in Dublin have been buried. Fifty of these corpses were not identified before interment.

Distressing scenes occurred at the funerals. Owing to the difficulty experienced in obtaining coffins, a number of the bodies were buried in shrouds. Only one mourner in each instance is permitted by the authorities to follow the remains.

On several occasions the police have opened and searched coffins in order to prevent the smuggling of arms out of the city.

The Countess Markievicz, who led a detachment of the rebels in Dublin, has had her sentence of death commuted to one of penal servitude for life.

George Plunkett, a brother of Joseph Plunkett, who was executed on Saturday, was also sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to penal servitude for 10 years. His mother, Countess Plunkett, has been arrested.

Sixteen other death sentences have been commuted. Henry O'Hannahan, one of the men thus respited, will undergo penal servitude for life. The other 13 men will be imprisoned for three years.

The total number of rebels deported to England has now reached 2,000. Two hundred rebel prisoners have been removed from County Galway, while another batch was brought into Dublin, where they were tried by court-martial and sentenced.