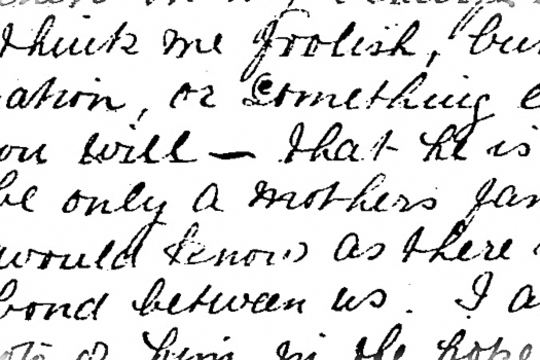

During and after the War, families would discover new ways to mourn.

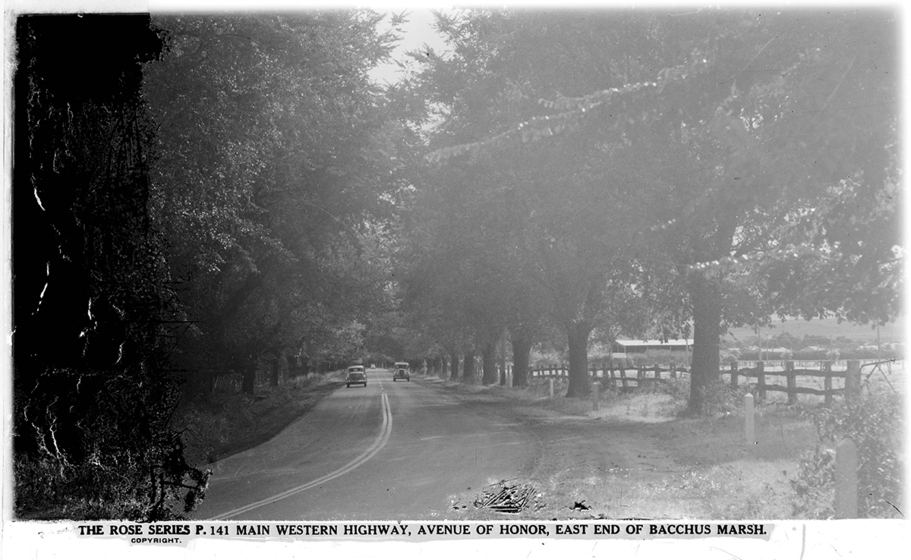

Monuments, honour rolls, avenues of honour, and cenotaphs within municipal districts and towns would be built to provide a focus for mourning relatives in the absence of a grave. Small mementos such as dog-tags, medals and letters of the dead would take on great private and personal significance.

Pictured here is the Bacchus Marsh Avenue of Honour, a tree-lined avenue planted in August 1918 in honour of locals who served in the First World War. Avenues such as this were planted throughout Australia and particularly in Victoria during and after the war.

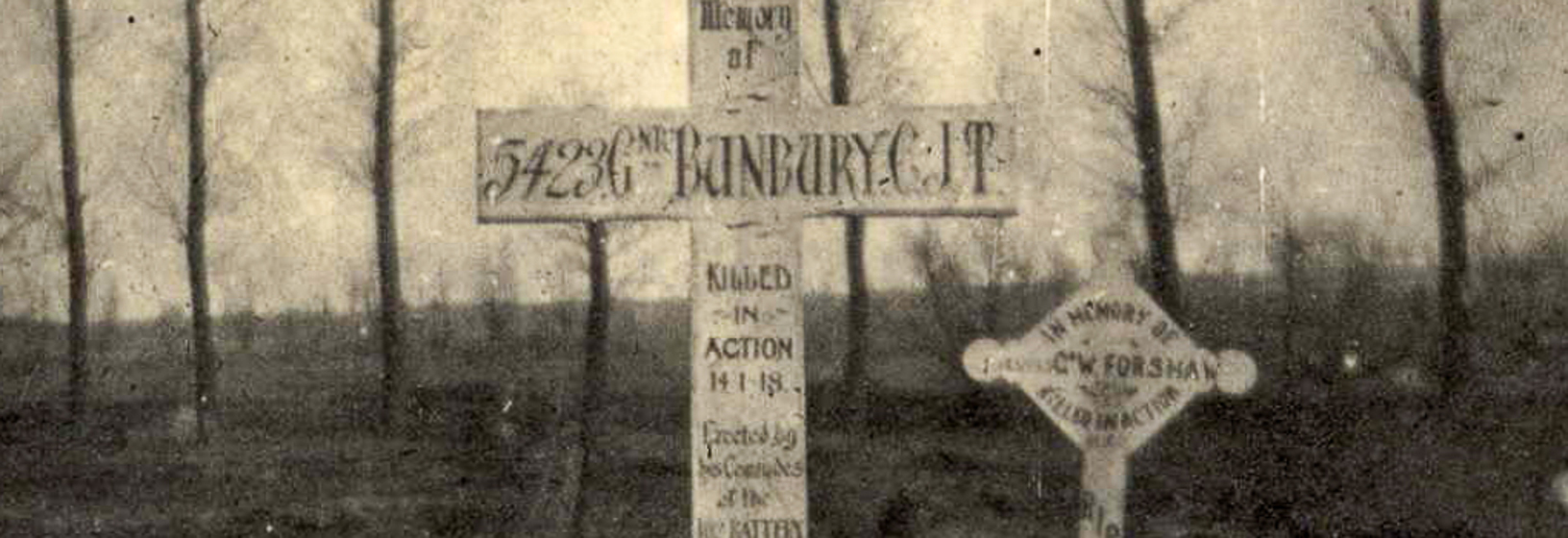

As the war progressed concern built within society about how and whether graves of loved ones were being cared for overseas. There was also great anxiety across the British Empire whether the bodies of those missing in action would ever be found. For Australians, so far away from the burial sites, this became a great burden of worry.

Part of the concern was due to changing societal expectations around how the government should honour the dead. Prior to WWI, officers might have been memorialised with grave markers, but most front-line soldiers were buried unmarked, often in mass graves.

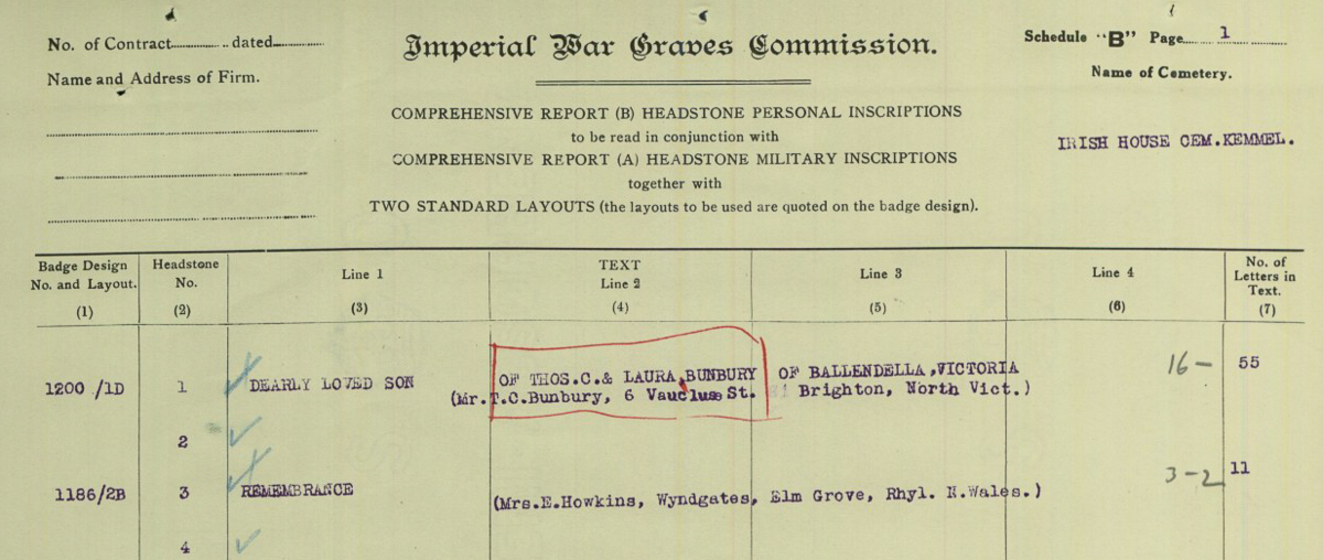

However by the early 20th century there was now a belief that every dead soldier should be equally treated and honoured with a gravestone.

The First World War would mark the first time in Australian and British military history that significant effort would be made to identify every soldier who fought and died.