The War Graves Workers

In 1919, 1100 Australian servicemen and volunteers returned to the silent battlefields of Europe and Turkey to locate graves, identify the missing, and exhume and rebury the dead in Commonwealth cemeteries.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this page may contain culturally sensitive information, and/or contain images and voices of people who have died

See story for image details

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

In 1919, 1100 Australian servicemen and volunteers returned to the silent battlefields of Europe and Turkey to locate graves, identify the missing, and exhume and rebury the dead in Commonwealth cemeteries.

Photograph - Burial parties and relocating bodies to proper graves (assumed to be France), c. 1919, Marcel Pillon Photographic Collection, ANZAC House

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

In April 1919, The Sun reported the Australian Graves Detachment had been formed to search the fields of Europe. “The work will take considerable time, but is regarded as sacred duty by all Australians to their fallen comrades,” the paper wrote.

A few months later, The Mercury reported from the now-silent Gallipoli peninsula revisiting the places of the Anzacs that “skeletons are still to be seen, showing where the wounded men managed to get into a bush or a little scrub to die. The outline of the body is still there, with knitted socks, puttees, and other fragments sufficient to identify”.

The Australian graves effort post-war occurred across three fronts: The Graves Registration Unit (GRU) at Gallipoli, the short-lived Australian Graves Detachment (AGD) and its replacement the Australian Graves Service (AGS), on the Western Front.

Photograph - Burial parties and relocating bodies to proper graves (assumed to be France), c. 1919, Marcel Pillon Photographic Collection, ANZAC House

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

The AGD (Australian Graves Detachment), in particular, was made up of 1,100 men—a mix of volunteer ex-soldiers and new recruits, who had enlisted too late to see action.

Private Will McBeath was one such late recruit, still training in England when the Armistice was announced. Veteran volunteers included the Indigenous war veteran Edward Smith and Frank Cahir MM DSM, who was at the Gallipoli landing and then the Western Front.

The AGD worked in the fields at Pozières and Villers-Bretonneux, which had seen significant Australian loss of life. Detachment worker William Lee wrote “I had the interest of the work at heart, I had fought over areas with our troops and knew all its associations and tragedies”.

Photograph - Burial parties and relocating bodies to proper graves (assumed to be France), c. 1919, Marcel Pillon Photographic Collection, ANZAC House

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

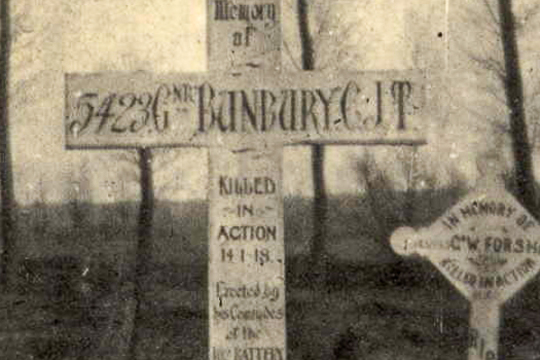

Working alongside Canadian and British teams, the AGD searched the battlefields with shovels and stakes to locate burial sites, find unrecorded bodies, and exhume remains.

Bodies were wrapped in canvas or hessian, tied with rope and taken by stretcher on horse-drawn carts to be reburied in a Commonwealth graveyard. Workers would consult with families back in Australia to determine gravestone wording. Once finalised, graves were carefully photographed as mementos for families.

The work was ghastly and unpleasant. The AGD often came across corpses that had lain exposed to the elements for months or years. Henry Whiting wrote “I can assure you it is a very unpleasant undertaking. Mainly all the men we have raised up to date have been killed 12 months and they are far from being decayed properly, so you can guess the constitution one needs. I have felt sick dozens of times.”

Photograph - Burial parties and relocating bodies to proper graves (assumed to be France), c. 1919, Marcel Pillon Photographic Collection, ANZAC House

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

It was also dangerous work—active hand grenades and mines were a real threat, the ground was filthy, and the process of exhumation, transportation and reburial, physically exhausting. Will McBeath wrote “this week we have reburied 200 men... You would hardly think there were so many graves in the field… there are hundreds to come in yet.”

In some cases, men of the AGD were digging up people they knew. In other cases, they were doing gruesome detective work, digging up decaying unrecognisable bodies in mass graves and looking for any clue to the dead man’s name—an identity disc, pay book, letter or photo. William Lee wrote about why he persevered: “We carry on knowing we are identifying Australian boys who have never been identified. “

Photograph - Burial parties and relocating bodies to proper graves (assumed to be France), c. 1919, Marcel Pillon Photographic Collection, ANZAC House

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

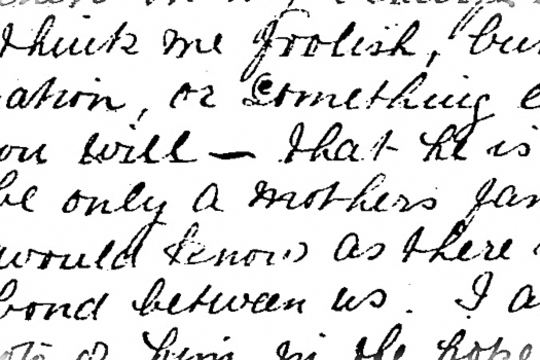

The grim routine took a lasting emotional toll. Frank Cahir volunteered for Graves Detachment duty in Europe without returning to his family in Victoria. When he finally did return, in 1921, he struggled adjusting to life in Australia, eventually suiciding; leaving behind a young family.

Frank Cahir’s example illustrates how difficult it is to understand what motivated these men, particularly the volunteers, to take on the work. Letters from the time show they drew on a mix of duty, loyalty and faith, sometimes simply needing to postpone the uncertainty of life after war. But the work was clearly tough to cope with.

Photograph - An outdoors group portrait of unidentified members of No 5 Company of the Australian Graves Detachment taking a break from their work at the Villers-Bretonneux cemetery, June 1919, Australian War Memorial

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Public domain

This media item is listed as being within the public domain. As such, this item may be used by anyone for any purpose.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

By mid-1919 there were reported incidents of alcohol abuse, mutinous and risk-taking behaviour and accusations of impropriety. Two official inquiries into the AGD’s irregular performance were held, leading to a change in leadership.

The restructured Australian Graves Services (AGS) took over graves duties on the Western Front until 1922. Work undertaken and completed by the AGD, their companion units, the AGS and GRU, and associated Commonwealth workers left a lasting legacy for a 20th century community trying to resolve its sense of loss and grief.

Photograph - Tracey Hind, 'War graves, Australian War Memorial Villers-Bretonneux', 2011, Flickr

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This media item is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). You may share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) and rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item provided that you attribute the content source and copyright holder, and identify any alterations; do not use the content for commercial purposes; and distribute the reworked content under the same or similar license.

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Tracey Hind

Not all the missing were found.

This resulted in the erection of massive monuments at Villers-Bretonneux, Menin Gate and Lone Pine; places where their names would be recorded in perpetuity. But the regular, peaceful monuments and graves in those foreign cemeteries owe a great deal to this unique group of men who took on the harrowing task of looking after our dead.

False Hope of the Missing

False Hope of the Missing

The Red Cross Information Bureau

The Red Cross Information Bureau

A New Equality in Death

A New Equality in Death

A Memorial at Home: Building the Shrine

A Memorial at Home: Building the Shrine

Emma Tout: Grieving Mother of a Missing Son

Emma Tout: Grieving Mother of a Missing Son

Vera Deakin's Search for the Missing

Vera Deakin's Search for the Missing

Stanley Addison: Red Cross Searcher

Stanley Addison: Red Cross Searcher

Miss Brotherton from Castlemaine: Red Cross Bureau Volunteer

Miss Brotherton from Castlemaine: Red Cross Bureau Volunteer

Frank Cahir: Graves Detachment Photographer

Frank Cahir: Graves Detachment Photographer

William McBeath: Graves Detachment Digger

William McBeath: Graves Detachment Digger