Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this page may contain culturally sensitive information, and/or contain images and voices of people who have died

See story for image details

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Film - 'Interview with Auntie Joy Wandin Murphy', Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Film - 'Interview with Auntie Joy Wandin Murphy', Koorie Heritage Trust

Joy Wandin Murphy: Hello, my name is Joy Wandin Murphy.

My name Wandin is my family name.

The tribal name is Wandoon and our relationship to William Barak or Beruk as we knew him is that he is my grandfather, Robert Wandin's nephew.

So, Barak to us was a man of great wisdom, a great leader and a man that knew how to keep his feet on the ground and that I think demonstrates the way in which the movement from Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, um.....manifested.

He was very strong with his thoughts but also a man that could connect to other people. He managed to converse with other people because he knew that they were not going to continue to survive if they didn't have the help of others.

Barak had met up with this Scottish woman named Annie Bon up at the Acheron Annie Bon actually went on to become part of the Members of Parliament and he would enable people to write how they felt about issues and then he would take those petitions along to Annie Bon firstly and then she would get them into the House of the day.

During those struggled times, there were many leaders but it seemed that Barak was the leader. Leading deputations to the Government in that time was a really big thing. But he knew how to do that in a way that he would get some response.

The issues were about the health of their community, there was a great deal of sickness there.

They certainly had enough food but the cultural activities and being able to continue living in a cultural way was a big issue.

The lifestyle on Coranderrk was a very missionary approach. But the women were very strong about keeping their cultural activities alive.

So at night-time, my grandmother would call the women inside and they'd all go in... into her little house and speak the language.

The men would go off doing their fishing things at night and doing their hunting.

And in the morning, there were prayers. There was a bell that would ring to say everyone must come together and attend the church and have prayer time.

So they obeyed all those rules because it meant that there could be a relationship but also, the people, you know, from being brought from so many backgrounds, so many clan groups, is that they felt that they needed to have that other belonging and a lot of them believed in the Church itself.

So prayers in a way were not something that they were uncomfortable with but they also knew and still were very proud of their own culture.

It became the most self-supporting station in Victoria. In fact, their produce such as bread and milk would be transported down to Lilydale and that was quite an effort in those days from Lilydale, which is about 22km in distance.

And of course, the township of Healesville was supplied with all of that produce as well.

So they made their own bread. Of course, they had cows to milk. They had quite an establishment like a little supermarket where they had their own eggs and so forth.

They also had a beautiful operation with a kiln where they made their own bricks that today is still standing. 'The manager's mansion' as they called it was made of the local homegrown bricks.

Barak was a... cultural soul. He was very apt in throwing the boomerang, the wangoom. He was one that was able to make many of the artefacts, had very skilled hands to make spears

and waddies and whatever else was needed as were most of the men on Coranderrk.

He also was a man that could sing. He could do a beautiful chant. He could dance.

There's not much, really, that I think that he couldn't do.

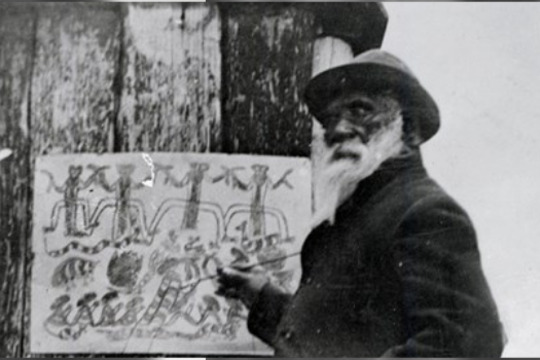

When he started painting, it was a way of him saying that these are what happens in our cultures. He painted the figures and the cloaks, the animals of the land, the weapons they used and the fires to show people how ceremonies took place.

But what we believe is that what he wanted was people to remember those ceremonies so that if he painted them - and those paintings have become internationally famous - then people would always know about the ceremonies on Coranderrk and of Wurundjeri people.

You know, I think about the time of his passing and it was, he actually fell into the fire and burned his hand and that in itself is significant to me because I believe that Barak's put the fire back in our belly.

When I tend to feel that we haven't got much hope, well, then, I think about those times that they had on Coranderrk.

I wish I had been there to feel the real strength but I do feel the strength and certainly Barak and other leaders, I believe, have given us that fire in the belly and we should cherish that.

This painting here, we believe it was painted in the late 1800s, maybe early 1900s, and the use of contemporary paint there together with ochre, it depicts a ceremony which Barak was very famous for painting.

It shows you that they wore a headdress, that they had wangooms or the boomerangs which they'd clap because the boomerang for us is our traditional instrument.

The two shaped like horseshoes are fires and incidentally with those two fires was when there was a ceremony, when a neighbouring clan would come to visit, the two ngurungaetas would stand each side of the fires and discuss and make agreements about the neighbouring community and how long they would stay for and what they were able to do and what the protocols were, so the fires were very significant and you can see there's quite a gathering of dancers and the stance of the dance was quite significant and still is today.

The cloaks that the two headmen are wearing here and the bottom which are women, we believe that it was only elders who wore cloaks.

Those cloaks were made of possum skins. And the dress that is worn with the top for young men, we're figuring that that might just be canvasy type things and it's been painted with the contemporary colour and some ochre as well.

I would imagine that that has been a ceremony at some time. I don't believe that Barak has just painted that with a picture in his mind. I believe he painted the living things.

I'm very, very proud and happy that we have this painting back here where it should be, in Australia for a start. And secondly, housed here at the Trust.

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? Yes

Conditions of use

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

This media item is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). You may share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) this item provided that you attribute the content source and copyright holder; do not use the content for commercial purposes; and do not rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) the material.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Professor Joy Wandin-Murphy, AO, speaks about her ancestor, William Barak.

Film - 'The William Barak collection at the Koorie Heritage Trust', Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Film - 'The William Barak collection at the Koorie Heritage Trust', Koorie Heritage Trust

The William Barak painting is one of the treasures that the Trust has here in its Collections. It was purchased by the Trust back in 1983 from an auction house. William Barak was a Ngurungaeta for the Wurundjeri people and that means Clan leader. He spent the latter part of his years on Coranderrk Reserve, which was from 1863 to 1903, where he became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights, and particularly the rights of his people on Coranderrk Reserve.

William Barak did the majority of his paintings around the 1880s and 1890s and this particular painting isn’t actually titled but is consistent with the majority of Barak’s paintings, in that it depicts ceremony. We can see in the top half of the image we’ve got these four figures and we’ve got men with beards and they’re clapping boomerangs. Boomerangs were used as our musical instruments down here they didn’t actually use the didgeridoo. We’ve got two figures in the bottom half of the painting and they’re dressed in possum skin cloaks, again we can tell that they’re men because they’ve got these beards and there’s a row of women seated at the bottom of the painting as well and it looks like they’re clapping. They may also have been beating possum skin rugs that were stretched over their knees that were sometimes used as drums and you can also see the feather of what looks like a lyrebird as part of their headdress as well.

In 2006 we took the William Barak painting to the Centre for Conservation of Cultural Materials to get the painting conserved and as part of that process the conservators did some infrared work on the painting…and they came across some under-drawings and a map underneath the actual painting we can see William Barak’s sketches that he did in pencil which shows some of the features of the face and different aspects of the painting and we can also see what appears to be a type of map and we can pick up words like Chamber and Wash Drive which make us think that it may be some kind of map related to mining or something similar. So this shows us that William Barak was actually using second hand materials for part of his painting and I guess if we’re thinking about William Barak having access to materials perhaps someone on the Mission or the Mission Manager was supplying him with materials so that he was able to complete his paintings.

The Trust is also fortunate to have two artefacts by William Barak in our Collection and these artefacts, the shield and the club were purchased by the Trust back in 1994 from a private collector who bought them years previously from a shop called “Decoration” in Little Collins Street. Both the shield and club are quite typical of the types of artefacts that we see down here. This shield here has these concentric diamond designs and the club itself is also quite typical in terms of the style and designs. Both of these artefacts have inscriptions on them in ink that say “Made by King Barak, last of the Yarra Tribe 18/12/1897. So this actually would have been written by somebody else on behalf of Barak because Barak himself couldn’t write. These are the only artefacts that I am aware of that William Barak made, that still exist in collections today. We do know that Barak made a range of different artefacts in his time at Coranderrk.

He made things obviously like shields and clubs but also spears and wooden lighters. It’s quite likely he was actually using a combination of traditional and contemporary tools to actually make the artefacts so with the designs on the shield we can see that these were most likely carved out with a pen knife whereas traditionally designs would have been carved with things like a possum jaw. Glass was also used to smooth the surface over. As an artist and craftsman Barak was very proud of his culture and he was able to share his culture by making things like artefacts, the paintings and things that he made but also by doing boomerang throwing, showing people how you start fire and those types of things. Around this period of time lots of people were coming up to the Missions and actually looking for souvenirs to buy and take back with them. So these artefacts represent that period in time.

Many artefacts were also made as gifts to dignitaries where they led Deputations down to Government and handed over a range of artefacts to either the Kings, the Queens or the Governors of the time as a way of kind of connecting them and getting their message across.

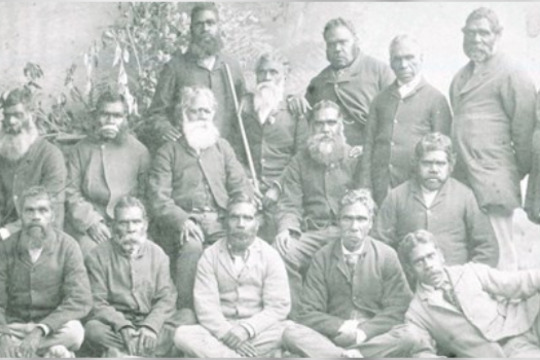

This image is of the deputation of 1859 led by Simon Wonga who was leading the Yarra and the Goulburn tribes down to the Governor requesting that land be set aside for them. Here we can see one of the Protectors William Thomas and he’s interpreting on behalf of the Aboriginal community for rights to land and in the foreground here we’ve got what looks like a possum skin cloak folded up with some clubs, some spears and a shield. Barak himself led a number of Deputations down to Melbourne from Coranderrk after the passing of his cousin Simon Wonga.

The Barak artefacts and painting in the Collection are quite significant to us because of who Barak was as a person but also because we don’t have very many items that date back to the late 1800s we can attribute to a specific individual, so for that reason these items are very important to the Trust and very significant to the community.

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Senior Curator at the Koorie Heritage Trust, Nerissa Broben, talks about items in the Trust's William Barak Collection: a painting, a shield and a club.

Film - 'When the Wattles Bloom', Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Film - 'When the Wattles Bloom', Koorie Heritage Trust

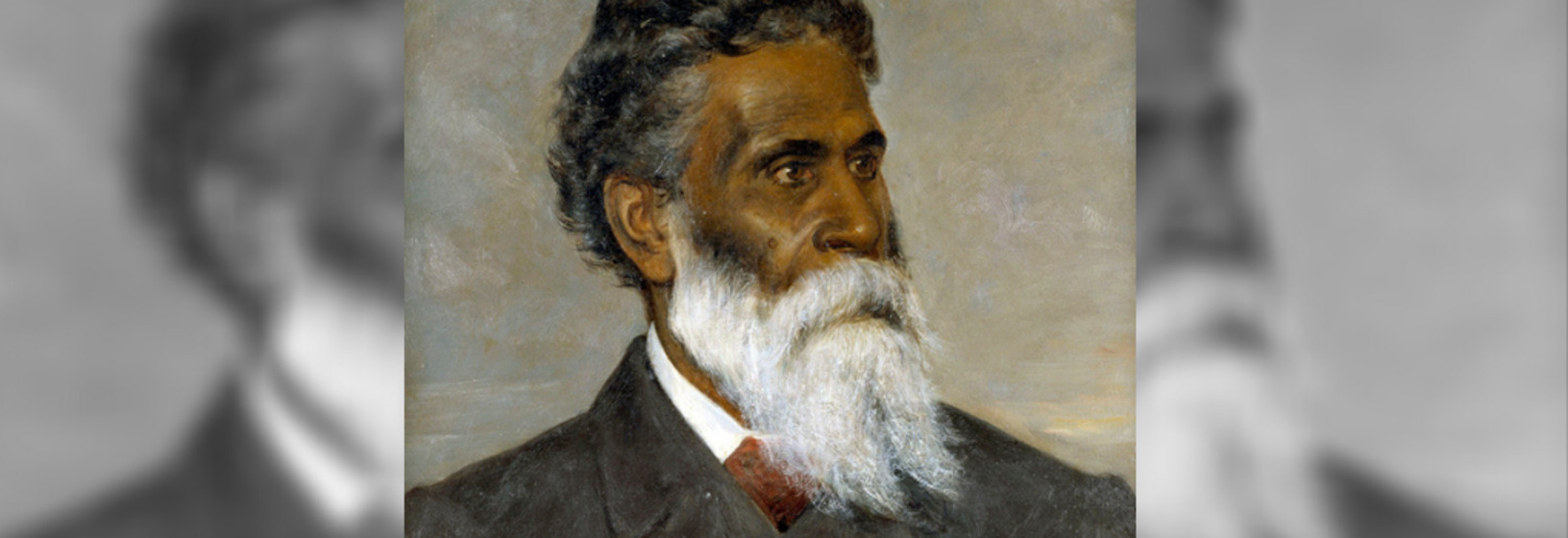

When the Wattles Bloom is a book by Shirley Wiencke. It’s about the life and times of William Barak who was born about 1823 to the Wurundjeri clan, a group of the Woiwurrung people. The title refers to Barak’s prediction that he would die when the wattles bloomed.

He saw a lot of the history of the early times of the Port Phillip settlement. He was a witness to the signing of the Batman treaty. His father was a Ngurungaeta, an Elder, of the Woiwurrung people and was a signatory to the document. Later Barak was attending the George Langhorne Mission School for a few years and then, as a boy of nineteen, he joined the Native Police. He has an amusing story to tell about this, in that they were searching for the Kelly Gang and had them, they thought, in some scrub and they suggested that William go in, but he told them that they should go in first because they had the guns. They decided not to do anything an’ called back for reinforcements. Shirley Wiencke also refers to a recording by Barak entitled “My Words” which tells of his life and times. This was done up at Coranderrk under the supervision of the Superintendent who had someone record this for him and it gives quite a few details of his early life.

Barak was also in demand by historians and anthropologists, as he had a store of knowledge about the Aboriginal people’s law and their stories, myths and legends, some about the beginning of the Yarra River, others, Creation stories. The Protectorate, which was operating at the time, bought land at Healesville and decided to set up a Reserve for the Aboriginal people. After serving in the Native Police, Barak joined his people there and lived there for the rest of his life. He was to become a Ngurungaeta himself, as his uncle, father and cousin Simon Wonga, had been before him and he took this very seriously.

He walked many miles to Melbourne from Healesville to see the authorities on the concerns of his people and became a well known figure, in fact, Governor Loch gave permission for him to be admitted to Government House at any time he arrived at the gates. He followed up his peoples concerns as a Ngurungaeta and he also spoke with visitors to Coranderrk quite freely. He was married twice and both his wives predeceased him. He had one son David and it broke his heart when David died at fourteen. He had a long life serving his people but he died in 1903, when the wattles bloomed in August.

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of Koorie Heritage Trust

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Judy Williams, a librarian at the Koorie Heritage Trust, discusses Shirley W. Wiencke's book When the Wattles Bloom about the life of William Barak.

Film - 'Remebering Barak', National Gallery of Victoria

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Film - 'Remebering Barak', National Gallery of Victoria

Judith Ryan: The great Wurundjeri artist William Barak occupies a unique place in the history of Indigenous Australian art and is also central to the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

The gallery was founded in 1861 in country of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation.

Two years after its founding in 1861, Barak, with other members of the Kulin nation, went on a long journey ending up back in his country at Coranderrk near Healesville, about 60km north-east of Melbourne.

He lived for the rest of his life at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station. And he developed such a reputation that by the time of his death in 1903, he was the most famous Aboriginal person in the whole of Victoria and arguably the whole of Australia, and the only one renowned as an artist in his own right.

Australian photographers visited Coranderrk and took photographs of Barak and other Wurundjeri people because Barak had become a celebrity renowned for his demonstrations of boomerang-throwing, his storytelling and also the watercolour drawings that he made of his own culture particularly recording ceremonies, hunting, flora and fauna and aspects of customary ritual prior to European colonisation.

When we think about Barak's position in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, it was Dr Ursula Hoff, the keeper of prints and drawings who happened to make a visit to a Balwyn private collector in 1962, a century after the founding of the NGV. And there, she encountered two remarkable drawings made by Barak.

One in Christmas 1898, Figures In Possum Skin Cloaks, and the other, a drawing of a Wurundjeri ceremony made around the same time. These works which she decided to purchase for the National Gallery of Victoria were the first works of Barak to be purchased by a public institution in Australia and this was long before the National Gallery of Victoria had its own Indigenous art department or any funds for the purchase of Indigenous work so it was as an artist that Dr Ursula Hoff responded to these works of Barak.

When we look at the drawing Figures In Possum Skin Cloaks of 1898, we see that he was recording the possum skin cloaks worn by senior men which also are used to wrap around the body of deceased Aboriginal people from Victoria.

We see that he is recording the sacred designs belonging to the Wurundjeri people and he's also recording elements of his country.

As he passionately remarked too when questioned about Coranderrk and the importance of Wurundjeri people staying in this particular place, he said that it was important to stay near the Yarra River because this was his country.

There was no... The mountains and the river of the Murray where he had been living prior to moving down to Coranderrk meant little to him.

When the National Gallery of Victoria held an exhibition Remembering Barak on the centenary of his death, a very well-known and important Dhalwangu elder from North-East Arnhem Land, Gawirrin Gumana, when he saw the portraits of Barak and the paintings of Barak, remarked that he believed that his ancestor had come from the waters of North-East Arnhem Land, made a long journey down to Victoria and had passed on his sacred designs straight to Barak who was actually also a member of the Dhalwangu people. So much was the affinity and the power of the work that Gawirrin, one of the great Yolngu artists of our generation who at that stage had been painting continuously for over four decades, he witnessed that this was an important man, important elder and felt a spiritual affinity with him.

There is no doubt that Barak was a remarkable man. Not only was he highly regarded at Coranderrk but also he made strong connections with the non-Aboriginal community of Victoria.

His fame was immense. Many important visitors came out to Coranderrk, including representatives of the British royal family, the Governor of Victoria, Henry Locke, and others.

And the interesting thing is that when these important people came to Coranderrk, they came wanting to see performed for them but at that stage, the Moravian order had forbidden the Wurundjeri people to perform ceremonies at Coranderrk so all that they could provide for these visitors, like any tourist anxious to see a little sort of glimpse into the world of the romanticised other, all they could provide for these visitors were Barak's drawings of ceremonies that he had participated in prior to European contact.

He produced a remarkable body of work. There are about 50 drawings extant, many of which are in collections overseas, mainly in Germany.

But one of the things that Barak did was to create a precedent because Coranderrk was really the first Aboriginal arts centre.

There are many of these art centres existing today where artists are supported and works of art are made for sale, for trade, to Europeans or non-Aboriginal people.

Coranderrk was the first of these enterprises. Women made money by making baskets, sedge-woven baskets.

Barak and others performed demonstrations of boomerang-throwing, told stories and made drawings.

Barak also was an innovator. He was interested in using new materials. He loved working on paper, experimenting with watercolours and gouache along with the ochres used in body painting or cave painting of Wurundjeri people. So he mixed new materials with organic pigments.

He was able to experiment with lateral perspective,with the sort of perspective that he obviously encountered when he had meetings with artists. He used to meet with Loureiro and other well-known Australian artists. And that was one of the things he was spreading...

He was an informant for Howitt and other anthropologists and through his dealings with Europeans, he ensured that the true stories of his culture live on and the beauty and spirituality of it is passed on to future generations and that is his importance to the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria which still remains on country of the Wurundjeri people.

Reuse this media

Can you reuse this media without permission? No (with exceptions, see below)

Conditions of use

All rights reserved

This media item is licensed under "All rights reserved". You cannot share (i.e. copy, distribute, transmit) or rework (i.e. alter, transform, build upon) this item, or use it for commercial purposes without the permission of the copyright owner. However, an exception can be made if your intended use meets the "fair dealing" criteria. Uses that meet this criteria include research or study; criticism or review; parody or satire; reporting news; enabling a person with a disability to access material; or professional advice by a lawyer, patent attorney, or trademark attorney.

Attribution

Please acknowledge the item’s source, creator and title (where known)

© Copyright of NGV Australia

The reuse of this media requires cultural approval

Judith Ryan, senior curator of Indigenous Art in the National Gallery of Victoria, discusses the life and work of William Barak.