Phrasebook Use in China

While many may imagine early China as being closed to the outside world, China was in communication with a wide range of countries. As early as 1276 an 'Office of Interpreters' was established to assist with communication.

Some of the earliest Chinese phrasebooks, created during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), were not to assist users speak English but to speak southeast Asian languages, such as Vietnamese, Cham and Malay.

By 1836, however, dictionary and phrasebook author and publisher Samuel Wells Williams observed how the circulation of manuscripts containing transliterated English words were now common in Canton (now Guangzhou) [see map below].

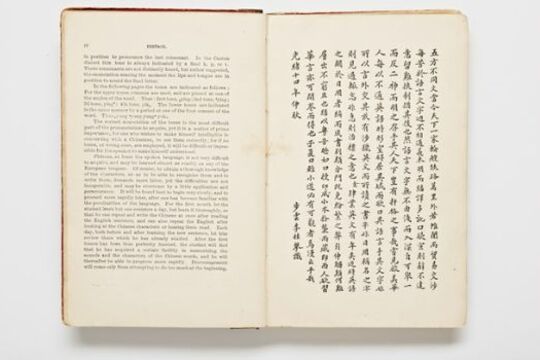

These phrasebooks record the sounds of the foreign language using a sequence of Chinese characters which, when read aloud in the appropriate dialect, approximate the sounds of the target phrases in the foreign language.

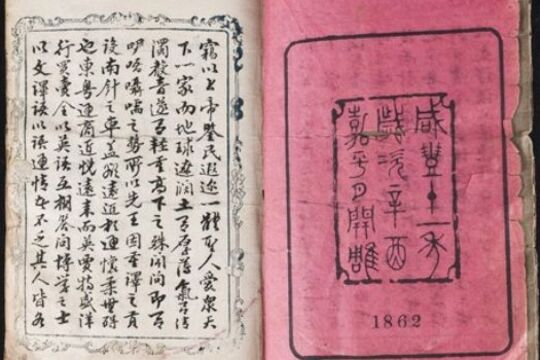

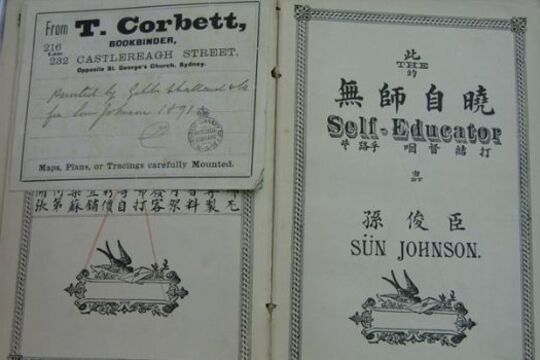

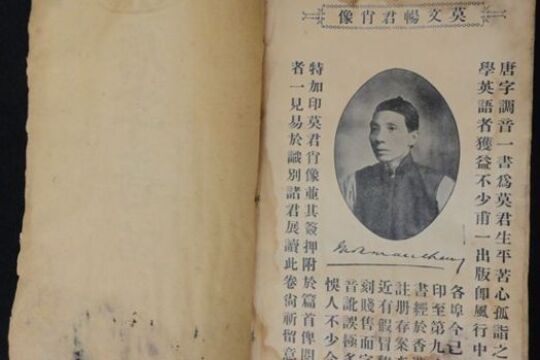

Over the course of the nineteenth century many different Cantonese-English phrasebooks were created by different publishers both in China and overseas. Some were designed for Cantonese speakers, others for English speakers and some phrasebooks, such as The Chinese and English Instructor by Tong Ting-Ku (1862), assisted Cantonese readers speak English and English readers speak Cantonese.

A short essay by the Chinese Museum, 2013.